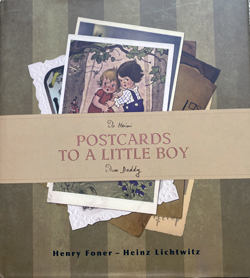

JACKSON, Wyoming — This story is built around 50 delicate letters, most written on the back of German period piece postcards: including garden scenes of fairy tales gnomes, elfs, leprechauns, and teddy bears designed for children. The letters, starting in February 1939 were by Max Lichtwitz, a Berlin lawyer, to his six-year-old son Heinz or Heini Lichtwitz, the future Henry Foner. They evoke love, longing, and irreparable loss. Max, a widower, sent his six-year son Heinz to England to live in Swansea, Wales with Morris and Winifred Foner. Max, his new wife and stepdaughter never got out of Germany, and were murdered in Auschwitz.

JACKSON, Wyoming — This story is built around 50 delicate letters, most written on the back of German period piece postcards: including garden scenes of fairy tales gnomes, elfs, leprechauns, and teddy bears designed for children. The letters, starting in February 1939 were by Max Lichtwitz, a Berlin lawyer, to his six-year-old son Heinz or Heini Lichtwitz, the future Henry Foner. They evoke love, longing, and irreparable loss. Max, a widower, sent his six-year son Heinz to England to live in Swansea, Wales with Morris and Winifred Foner. Max, his new wife and stepdaughter never got out of Germany, and were murdered in Auschwitz.

On June 18, 2020 Yad Vashem presented a zoom program, “Postcards To A Little Boy – Reflections of a Kindertransport Child,” featuring 88-year-old Israeli Chemist Henry Foner. He made aliyah in 1968. We viewed the 8 pm Israel presentation at 10 am in California. The presentation was so personally moving I wanted more.

Yad Vashem in Jerusalem sent me a review copy just in time to take to read in Jackson Hole to where we were fleeing, a trip romantically reminiscent of the several young ladies and three beaus fleeing Black Death maelstrom Florence in 1347. That experience gave birth to Giovanni Boccaccio’s rollicking and revealing Decameron. Our 784 mile flight from Los Angeles to Wyoming took only a little bit longer than the two mile trek to a villa by Boccaccio’s frolicking story tellers and servants by horse and donkey.

We learn differently in the pandemic. Zooming exposes topics, talks, and other educational opportunities that were not previously available or accessible. Local zooming had the advantage of no driving, no searching for parking, no getting dressed up. National and international zooms have brought great conversations, including 94-year-old Yehuda Bauer, into our living rooms, and generally at no cost, of course donations were welcomed. Distance learning has limitations, just try to have an Apple consultant talk you through an online computer repair.

My interest in the Kindertransport, the ten thousand German, Austrian and other European Jewish children sent by their parents to England just after Kristalnacht in November 1938, is longstanding. Nonprofits and NGO Rescue attempts were valiant, too few, too limited and for many, too late. They tended to reach the children of Jewish elites, lawyers, doctors, dentists, scientists. For instance, in America Alvin Saunders Johnson, President of the New School in New York established “The University in Exile,” and attempted you bring children to a farming community in Wilmington, North Carolina. My mother was too old to qualify for the Kindertransport; she contemplated escaping to Shanghai but managed to get a visa to England as a mother’s helper or nanny.

Germany pioneered the production of colorful postcards in the early 20th century. Most of Henry’s postcards were published by Kunstverlag Oppel in Jena, some can be found on eBay. Henry’s adoptive parents, the Foners, saved the postcards. In 2002 Henry shared them with Yad Vashem and they encouraged him to make his story more widely available.

Although this book first appeared in 2013 the story maintains its vitality especially as members of the Kindertransport generation age into their nineties. Holocaust Survivor reunions fade as the survivors dwindle, but their experience is not to be forgotten. American immigration policy and DACA echo the eternal quest for bettering life and parents parting from their children. The 2019 PBS special, Into the Arms of Strangers: Stories of the Kindertransport, documents how these child immigrants as adults contributed to society.

The vehicle for this story was postcards. Again, my mother, a German teenager in Hanover during the latter 1930s saved postcards. They were a genre children were eager to receive, they were colorful and came with usually pleasant greetings. Only one postcard was ominous. On August 31, 1939, Daddy wrote, “I hope war will not come. If he [sic] is coming although, God bless you and uncle and aunty!” War broke out in September of that year.

The exchange of letters was pretty much one-sided. The postcards that Vati or father wrote to his son survived. The letters by Heinz, Heini, and anglicized Henry to Vati (father) did not survive. Heini soon lost his facility in German and his father started writing letters in English to Master Heini, the English convention of address in letter to boys. Vati thanked his son for his progress reports. As usual, Max mildly chided Henry to write more letters more often.

There were several birthday cards from his English friends emblazoned with the number Seven. My mother saved all my birthday cards from my first eight years in England, all are emblazoned with the ordinal year. Almost all the cards contained the expression, “Many Happy Returns,” a trope I have written hundreds of times, but which is not part of our American English tradition. I will be sure to pull out my cards and enjoy again upon returning to Richmond.

The last letter, a Red Cross form from Berlin is dated August 12, 1942. Max typed, “Dear Henry, I’m glad about your health and progress. Remain further healthy! Our destiny is very uncertain. Write more frequently. Lots of kisses. [Signed] Daddy.”

Henry replied, on October 24, 1942, the only letter by Henry that survived, in 7-year-old longhand, “Dear Daddy, We are all well. Love to grandma and yourself. Kisses from me, Henry.” I have my Grandfather’s Red Cross correspondence from Theresienstadt; he had the good fortune to survive.

*

Pollak, a professor emeritus of history at the University of Nebraska Omaha, and a lawyer, is a correspondent now based in Richmond, California. He may be contacted via oliver.pollak@sdjewishworld.com

I read with personal interest your piece on the Kindertransport . My mother and her brother were smuggled out of Eslohe, Germany via the Kindertransport following Kristallnacht. The family was split up, but Mom was reunited with her brother and mother in London after arduous travels and hand-offs in Belgium and France. Quite an ordeal for a seven-year-old.