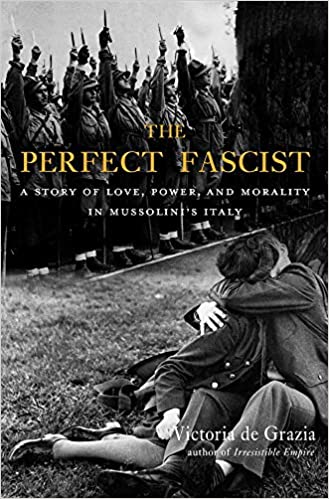

The Perfect Fascist: A Story of Love, Power, and Morality in Mussolini’s Italy, Victoria De Grazia, The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA 2020; 528 pages

By Mitchell J. Freedman

RIO RANCHO, New Mexico — Columbia University historian Victoria de Grazia, who has written extensively about women in Fascist Italy (How Fascism Ruled Women), and America’s imperial drive to spread consumer capitalism abroad (Irresistible Empire: America’s Advance through Twentieth-Century Europe), has written a book where its title and subtitle are telling two different, but overlapping, stories.

RIO RANCHO, New Mexico — Columbia University historian Victoria de Grazia, who has written extensively about women in Fascist Italy (How Fascism Ruled Women), and America’s imperial drive to spread consumer capitalism abroad (Irresistible Empire: America’s Advance through Twentieth-Century Europe), has written a book where its title and subtitle are telling two different, but overlapping, stories.

The main title is the first biography, in the English language, and maybe anywhere, of the life of Attilio Teruzzi (1882-1950), a Milanese wine merchant’s son who entered the military at a young age, served in North Africa as part of Italy’s attempt at empire building before and during World War I, and, after returning home from that war, found himself attracted to the growing Fascist Party movement under Benito Mussolini. Throughout the 1920s and 1930s, Teruzzi rose to the top echelons of Mussolini’s Fascist regime, though he never achieved Mussolini’s consistent close confidence. Despite being in the outside ring of Mussolini’s close circle, Teruzzi can be said to personify “the” perfect fascist, with his impeccably ironed and starched military uniform, decorum and formalistic public comportment, charismatic speaking ability, demand for others to obey strict forms of morality (even as he practiced various types of debauchery in his private affairs), a firm and unwavering support for, and belief in, Mussolini’s leadership, and a consistent hatred for anything that could be deemed socialist or liberal–with socialists being dangerous to the common good and liberals weak to a point of undermining the foundations and stability of civil society.

De Grazia cites a variety of Italian and English sources, and shows remarkable ability in explaining deep historical strains in 19th and 20th Century Italian, European, and international histories, as she describes Teruzzi’s humble beginnings, his early military adventures, political triumphs, and, eventually, Teruzzi’s ignominious and pathetic downfall and imprisonment.

Though de Grazia recognizes Teruzzi as a villain in modern European history, she provides a sympathetic perspective in recounting Teruzzi’s last days, when he was finally released from prison following a general amnesty, only to die suddenly within a few weeks of his release. De Grazia’s book provides as solid an explanation as any work I have read about the lure of Fascism in a stressed society, the type of people most subject to that lure, and how a totalitarian regime takes hold in a nation. Writing this book before and during this American Age of Donald J. Trump, de Grazia astutely avoids breathless comparisons to the present, though her storytelling allows readers to determine, for themselves, the ways in which fascist thinking and behavior are inherent, and easily penetrate into any modern society, not merely 1920s and 1930s Italy.

For readers of historically-based romantic literature, such as Diana Gabaldon’s Outlander series, it is de Grazia’s book’s sub-title that may grab such readers’ attention. Embedded within Turuzzi’s life story is a truly remarkable tale of love, power, and a multi-layered, yet hypocritical, morality. Turuzzi grew up in a strict Roman Catholic home located in cosmopolitan Milan in the last two decades of the 19th Century. Teruzzi’s mother’s strict religious morality competed, and often clashed, with late 19th Century Milanese liberal and secular culture, as Milanese artists and business people saw themselves as recreating the 15th Cenutry Italian Renaissance and subsequent Age of Enlightenment in a then-recently reunited Italy.

Teruzzi did not want to grow up to be a priest, and never saw himself living a monastic or celibate life. Instead, Teruzzi imbibed from his religious upbringing a romantic vision of order and ritual. Teruzzi did not idealize the clergy, who he saw as weak, but he did idealize military service and leaders. Throughout Teruzzi’s initial military career, whether serving in Libya, or other parts of North Africa, and later in the Fascist Militia at the height of Mussolini’s power and rule, Teruzzi saw himself as part of a national quest to raise Italy’s status to that of the leading European nations, and ultimately replicate ancient Roman glories.

For Teruzzi, Mussolini represented a logical step upward and forward from Guiseppi Mazzini, the mid-19th Century Italian politician and visionary most associated with the unification of Italy. Teruzzi’s other romanticism centered around Italian opera, less from a technical or aesthetic standpoint i.e. Puccini, Verdi, and Rossini, than seeking to attach himself to the celebrity status which leading opera singers, maestros, and opera house promoters in Italian and European society had achieved. Unlike the fascist poet, Gabriele D’Annunzio, Teruzzi was never interested in intellectual pursuits, nor did he appear to read much. Teruzzi loved action, and, in opera houses in Milan and elsewhere, he felt the electricity of being among wealthy and elite crowds, which his petit bourgeois parents had only seen from the outside. Teruzzi adored the excitement of listening to the soaring operatic music and seeing the dramatic stories. Most of all, Teruzzi saw how nearly everyone in Western Europe, from commoners to the elites fawned over opera composers, singers-actors, and maestros. For Teruzzi, this was a world he longed to enter, as he continued his climb to power with Mussolini and the Fascist Party in the early 1920s.

Enter a Polish-born, but American raised, up and coming opera starlet, Lilliana Weinman. Born in 1899, and 17 years younger than Teruzzi, Weinman arrived in Italy with her mother in May 1920. Weinman had traveled to Italy to complete her training as an opera singer, and arrived with recommendations from major international opera world personalities who had seen her perform. Weinman’s parents, who immigrated from the Galicia region in Poland to New York when Weiman was very young, had found surprisingly quick and significant economic success, owing to her father developing and patenting elastic webbing for trousers. Weinman’s parents were the personification of the ultimate get-rich-quick story, and had the money to buy their daughter lessons with top opera singer tutors, which led Weinman to meet important people at the New York Metropolitan Opera. Reviews of Weinman’s performances in major entertainment and news sources wrote of Weinman’s “beauty of voice,” “beauty of presence,” and “abundant temperament.” Weinman was also driven in that most modern American way. In her diary, in 1920, just before leaving for Italy, Weinman wrote: “I feel I will become a great prima donna, and a great prima donna’s prerogative is to take, not give.” This may sound sort of fascist in temperament, and, when combined with her parents’ new-found wealth, Weinman had already developed a perspective which favored the divine right of wealthy people to their money and power over socialist losers who struggled and suffered in tenements.

Not long after Weinman’s arrival in Italy, as the Fascist movement began to shake Italian civil society with their romantic, yet violent, militarism, Weinman found herself increasingly enchanted with this much older suitor, who maneuvered to find ways to meet Weinman and her mother at various locations throughout Italy. Each time they met, it seemed Teruzzi had achieved a new level or position within the Fascist Party, and, by 1925, had become an important figure in Mussolini’s Fascist movement, which was consolidating its power over Italy’s civilian government. Teruzzi eventually wore down Weinman’s resistance to a romantic commitment, and eventually Weinman decided to marry Teruzzi, who, by then, appeared as a dashing male lead in a romantic Italian opera. In accepting Terruzi’s marriage proposal, however, Weinman recognized cultural norms of the time required her to put her career on hold, perhaps permanently. For Weinman, however, she saw an opportunity to exercise power as the wife of a major political and military leader in a seemingly new type of society.

The pair married in May 1926, after a relatively short engagement. El Duce, meaning Mussolini, personally attended the wedding and reception, and, after the wedding, the pair met with Italy’s King Emmanuel. Teruzzi’s wedding party included the then-Fascist Party Secretary and the Militia General, the latter perhaps as important a military leader as any government-employed military leader at the time. There were 600 guests at the wedding, including the bride’s parents, the groom’s mother (the groom’s father having been deceased for some years), and captains of Italy’s industries. The New York Times, which remained fairly enamored with Mussolini during the mid-1920s through mid- to late 1930s, favorably reported on the wedding in its society page. The couple had a civil wedding, and, most importantly for future events, a separate church ceremony. As de Grazia writes, the mixed marriage of a Roman Catholic and a rather secular, but self-identifying Jew, “didn’t appear to be an obvious problem. Marriages between Catholics and Jews had become more common in Italy since the war…For Teruzzi, the fact that the brilliant, wealthy, and worldly Margherita Sarfatti, Mussolini’s helpmate and lover, was Jewish” was something which Teruzzi appears to have believed made him similar to Mussolini. De Grazia provides evidence that Mussoliini found Weinman deeply captivating, for her beauty, talent, and, especially her intelligence and wit.

It is noteworthy that Weinman was not Terruzi’s first Jewish lover. When Teruzzi was stationed in Libya, he had an intense sexual and romantic relationship with a Jewish woman, and seriously considered marrying her. De Grazia also writes Teruzzi and Mussolini were not alone among prominent fascists in having a Jewish girlfriend, mistress, or wife. De Grazia discloses how the leading fascist official in Milan, Roberto Farinacci, had a long-time office manager, Jole Foa, with whom he was at least professionally close, who herself was so comfortable and playful in her relationship with Farinucci that she often signed communications to him as being from his “Jewess.”

The Teruzzi-Weinman marriage initially appeared to be one built on mutual respect and love, but deteriorated within two years. De Grazia recognizes the limits of her sources, but was able to discover that Weinman became increasingly frustrated and angry with Teruzzi for his continuous affairs with various women, including teenaged girls who were daughters of people powerless to stop his predatory behavior. De Grazia also hints at Teruzzi’s pederasty, of which Weinman may not have been aware. In 1928, Weinman had begun to say to more than one acquaintance she would seek a divorce from Teruzzi if he did not stop his philandering. She had such a sense of entitlement, from her family status, and her status as the wife of an important fascist leader, with her own friends in high places in the United States and in Europe, that she had little consciousness or concern regarding the Catholic Church’s strict policy against divorce.

She was also oblivious to Mussolini’s finalizing what became a formal treaty with the Catholic Church to complete Mussolini’s consolidation of control in Italy. Just before the couple’s trip to New York in December 1928, Mussolini suddenly, and without warning, tapped Teruzzi to become chief of staff for the entire Fascist Militia. This required Teruzzi to leave his governorship in Libya, where he and Weinman basked as near lords over colonized people, and return to Rome for instructions and strategies. In this position, Teruzzi would be reporting directly to Mussolini, and nobody else. Weinman, having longed to return to visit her family in New York, decided to leave for New York, alone—though Teruzzi lovingly promised to meet her in New York a few months later.

In March 1929, Teruzzi, still in Rome, received and reviewed letters Weinman had written her last opera singer tutor in 1925 and 1926. The tutor had been in love with Weinman, and no evidence, apart from how one interpreted Weinman’s letters, she reciprocated. When Weinman became engaged to Teruzzi, and said she would place her career on hold, Weinman’s father abruptly terminated his tutoring services with not a care from Weinman herself. The tutor appears to have provided the letters to Teruzzi in revenge against Weinman and her family. Weinman’s letters to the tutor were written in an effusive manner that reasonably gave the impression of a romantic relationship, though, as those studying mid- to late 19th Century women’s letters to male and female friends have long noted the hyperbolic and effusive language did not denote a sexual relationship. Nonetheless, Teruzzi angrily sought a legal separation, and said, if he could not obtain a Church-approved divorce, he would seek an annulment of the marriage, particularly as Weinman had not conceived a child as a product of their marriage.

Weinman was both outraged at what she said was a lie about any romantic or sexual relationship with the tutor, and devastated at Teruzzi’s demand for a divorce or annulment—not to mention her concern she would lose the high position she had attained in Italian society. What follows in the book is far more about the annulment battle which stretched for over fifteen years in a Catholic Church increasingly under Mussolini’s regime’s power. The almost comical irony is Weinman prevailed at every level of the Catholic Church tribunals, convincing clerics of her sincerity, her denials of any affair with the tutor, and, for most of the next fifteen years of hearings and delays in hearings, her wanting to reconcile with Teruzzi.

De Grazia is adept in taking readers through the drama, heartache, and betrayal Weinman felt, particularly after Weinman learned Teruzzi had fallen in love with another woman, most ironically a Jewish woman named Yvette Blank, who had been living in Italy on a Romanian passport. As Mussolini’s Italy became more closely allied with Hitler’s Germany, and Italy passed, with Mussolini’s private reluctance, anti-Semitic and racist “Race Laws” in 1938, it became difficult for Teruzzi, and even Mussolini, to protect their Jewish mistresses, in Mussolini’s case, Saffati, and Teruzzi’s case, Blank.

Weinman had left Italy for New York City in the early 1930s, shortly after hearings at the first level of the Church tribunals. She found herself becoming her father’s manager of his now varied business enterprises, and doing well in that position. She returned to Italy for later hearings through at least 1938, and, again, prevailed with lawyerly assistance before Catholic Church clerics, who rejected Teruzzi’s petition for an annulment.

In 1939, it appeared the highest Church tribunal, short of the Pope himself, was considering siding with Teruzzi to grant his long-waited-for annulment. Then, in the fall of that fateful year, as World War II began in Europe, the Church appellate tribunal decided to place Teruzzi’s appeal on hold for what it said would be the still unknown duration of the war. Teruzzi was outraged and Weinman bitterly bemused. Yvette Blank, however, was concerned for her life and that of the daughter she had with Teruzzi because Fascist Italy’s official antisemitism deepened,

Blank’s dreams of marrying Teruzzi after the annulment were now dashed. Teruzzi, clearly worried about his daughter’s status as the daughter of a “Jewess,” used his now powerful position inside the Italian government to gain legal guardianship over his daughter, negating Blank’s guardianship, despite Blank’s expressed objection. Blank became estranged from Teruzzi, as she found herself increasingly vulnerable as a suspect alien who could not even return to Romania. She nonetheless stayed in Italy, for fear of never seeing her daughter again, though she recognized, every day she stayed in Italy, the more she endangered her own life.

Teruzzi’s ugliest personal moment came in February 1942, when Teruzzi, without warning, ordered Blank interned as an enemy alien in a camp on an island off Italy’s southern coast. In Teruzzi’s defense, the timing of this decision coincided with the Germans taking more control over Italy, after Italy’s disastrous losses in North Africa, and the British and now Americans moving through North Africa with plans to invade Italy. De Grazia writes, it was “well known” by the start of 1942 the “Germans deplored the fact that the Italians refused to take the racial issue seriously.” De Grazia implies Teruzzi may have sent Blank to the internment camp to protect her from the Germans rounding her up with other Jews to send to death camps in Eastern Europe. Nevertheless, Blank suffered terribly at the Italian internment camp, though, ultimately, as Teruzzi’s fortunes fell disastrously after 1943, Allied troops liberated the camp, releasing all prisoners, including Blank.

One may think Blank would be bitter toward Teruzzi, who had been arrested and placed into an Allied-controlled prison. Instead, Blank immediately traveled to visit Teruzzi in prison, seeking to rekindle their romantic relationship. She did this, even as she had independently regained custody of her daughter. To show her abiding love for Teruzzi, Blank rented a dwelling near the prison to ensure regular contact with him. At this point, Teruzzi was largely reduced to a pathetic status, though his love for Blank had clearly waned. However, he maintained, to his dying day, a strong paternal love for their child, Maria Celeste, affectionately known as Mariceli, who, in turn, revered and adored Teruzzi.

Meanwhile, Weinman returned to Italy after the war, and, in February 1947, sought a final ruling from the Church’s highest tribunal to affirm denial of Teruzzi’s annulment petition. In preparing her case, Weinman was granted access to Church papers regarding Teruzzi’s actions since 1938, and learned, for the first time, Teruzzi had fathered a child with Blank, who Weinman had previously seen as merely another of Teruzzi’s “whores.” Weinman also learned Teruzzi lied in official paperwork, stating under penalty of perjury Weinman had “consented” to making the child an heir to Teruzzi. Weinman was beside herself, writing to her mother, “What a pity. I wasted my life for such scum.” After learning she did not have grounds to sue for divorce on the basis of adultery, due to time limitations, and the fact Blank had never lived with them while Weinman and Teruzzi were cohabitating, Weinman spitefully ordered her lawyer to petition the Church to “disaffiliate ‘his bastard.’” It is not clear if this petition was granted. However, later evidence adduced in de Grazia’s book reveal a genuine and continuing father-daughter relationship that appeared legally sanctioned.

De Grazia does not spare readers from concluding Weinman was a vain woman and a fascist sympathizer, notwithstanding Weinman’s statements, in the last months of World War II, and after the war’s end, against Mussolini’s regime. Weinman never remarried, and, after her parents died at the dawn of the 1950s, Weinman operated, and eventually sold the family business, lived thereafter off her inherited wealth, and became a leading donor to the New York Metropolitan Opera. Weinman insisted on being known for the rest of her life as the “Countess Attilio Teruzzi,” as if Teruzzi was some sort of royalty. Weinman died in 1987, having been known by nieces and nephews as “a garrulous, exotic cousin, holding forth on life in Mussolini’s inner circle.”

In writing this book, de Grazia drew on private records of Lilliana Weinman, and Teruzzi, as well as a wide variety of letters of people with whom Weinman and Teruzzi were in contact. She also consulted a vast array of primary and secondary sources, as shown in the copious endnotes. As part of her investigations, she tracked down Yvette Blank’s granddaughters, then living in Naples. We also learn how Blank had vainly sought to help Teruzzi maintain any money or property he had accumulated, though she would never become Teruzzi’s wife. Blank eventually lived a life of a lower-middle class status with her daughter, Mariceli. The granddaughters were protected more through the Italian welfare state than anything gained from being related to a top ranked fascist military official. They knew little about their grandfather, other than a single photograph one of the granddaughters began to keep in the family living room after Mariceli died in 2013, and other than what de Grazia eventually informed them about their infamous grandfather.

As for Roberto Farinacci’s long time office manager, Jole Foa, in 1943, after managing to avoid being arrested and sent to a death camp, Foa was provided an open opportunity to escape to Switzerland. However, when she reached the Swiss border, she turned back, and, almost immediately, was arrested. Farinacci did not provide any further help, but, as de Grazia writes, “Farinacci was known to be helping other Jews, family men who had to have a certain wealth to pay all of the fees and bribes involved.” Farinacci was certainly not heroic, but he was not a Nazi monster. Foa was eventually sent to Auschwitz, and, when the Allies liberated the prisoners at Auschwitz, Foa was listed as an existing prisoner, but had somehow disappeared—or escaped—perhaps because she feared Allied reprisal for being a confidante of a leading Italian Fascist.

The Perfect Fascist is definitely a biography for our times. It helps us understand how and why business and religious leaders, and other elite sectors in Italy, embraced Fascism, and appeared to do so out of an inordinate fear of anything approaching “socialism,” where these elites stood to lose some money or some power. In the late 1920s, these often-reactionary elements believed they could co-opt Mussolini, and the Fascist movement, but ended up in a subordinated status within Mussolini’s dictatorial government.

However, there is a less important, but still intriguing, story in de Grazia’s narrative, and that is a story of resourceful Jewish women who loved these fascist military leaders, and how much various fascist military leaders respected these women’s intelligence and charms. Since World War II, and through today, in American literature, magazines, and broadcast media, American male Jewish writers, comics, and directors often caricature Jewish women as shrill, selfish, and often not physically desirable compared to “Shiksa Goddesses.”

Teruzzi, Mussolini, and other powerful European men would rightly find such portrayals deeply offensive. It is perhaps their one redeeming value that they saw the “Jewesses” in their lives as jewels in both intelligence and beauty. There is much to learn from Victoria de Grazia’s insightful biography of a fascist leader, much to admire in her prodigious research, and much to contemplate as we think about political analogies in our own time and in the United States.

However, I wish to emphasize de Grazia has performed a great historical feat in illuminating the independence, wit, intelligence, talent, and resourcefulness of Lilliana Weinman, Yvette Blank, Margherita Sarfatti, and Jole Foa. There is a miniseries in this multi-layered story, and it is one where the Jewish women characters will be viewed with sympathy and respect, even as these women made decisions and statements viewers with anti-fascist proclivities would find strong reason to criticize.

*

Mitchell J. Freedman is a lawyer by trade for nearly four decades, though he remained a continuing student of history. Her served as president of Ner Tamid Synagogue in Poway, California for nearly nine years, and is now living with his wife in New Mexico, where, presently, he teaches history to high school students. Freedman is also the author of the critically acclaimed alterative history, A Disturbance of Fate: The Presidency of Robert F. Kennedy, released in hardcover in 2003, and softcover and Kindle versions in 2011. He is the proprietor of the blog known as MF Blog, the Sequel at https://mfblogthesequel.blogspot.com/

Fascinating, thank you. Regarding the allusion to President Trump, I think in these times it is as important if not more to look at the rising power of the socialists -communists, who killed hundreds of millions, and the fascist techniques of the so-called anti-fascists in America today. Two sides of the same evil coin. Our young people know nothing about the twentieth century but their educators help them romanticize Marxism. See Rabbi Samuel’s June 18 essay.

With all respect, I hardly think AOC or Bernie Sanders wanting what much of Western Europe obtained, especially after WWII, is anything like Stalin, Mao, or even Trotsky. Our nation has a much deeper history of right wing vigilantes than left wing. I do not think Rabbi Samuel is a very good guide on this, though I am very impressed with much of his God and the Pandemic book for its Biblical research and scholarship.