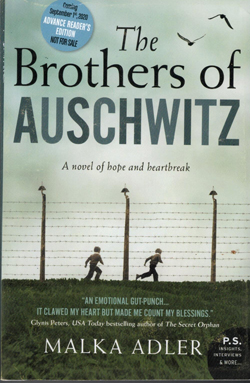

The Brothers of Auschwitz by Malka Adler; One More Chapter, an imprint of HarperCollins; ISBN 9780008-386122; 433 pages plus Author’s Note, Author Q&A; Reading Group Questions; $16.99.

SAN DIEGO — I have read and reviewed numerous Holocaust memoirs, but none hit me with the impact of this novel — perhaps because the author infused The Brothers of Auschwitz with such onomatopoeia as the sounds of machine gun fire, the clubbing of human beings, the whistle of death. This made the experience different from reading the more flatly narrated memories of Holocaust survivors; it stimulated me to not only read about the horrors of the camp, but to empathically experience them.

SAN DIEGO — I have read and reviewed numerous Holocaust memoirs, but none hit me with the impact of this novel — perhaps because the author infused The Brothers of Auschwitz with such onomatopoeia as the sounds of machine gun fire, the clubbing of human beings, the whistle of death. This made the experience different from reading the more flatly narrated memories of Holocaust survivors; it stimulated me to not only read about the horrors of the camp, but to empathically experience them.

This novel about two brothers — based on the memories of two fraternal survivors who lived in author Adler’s Israeli village — takes us beyond liberation to the refugee camps where soldiers and nurses tried to restore survivors to health, and eventually to Israel, where they made their homes.

Many sections of the book are riveting, but the one that made me sit up and mark Page 323 illustrated in graphic detail how the mind of a survivor, stricken with PTSD, works. Yitzhak recalled that newly arrived and put to work building the reborn nation of Israel, he and other survivors were asked to carry sacks of mash on their backs “and we saw the crumbling bodies of prisoners to be dragged to a large pile.” Given shovels to dig holes for trees, “we saw a pit for the dead.” When villagers played classical music, “we heard the orchestra of Auschwitz, and the screams of a mother….” The worst flashbacks were prompted by bonfires, and “I saw my family disappearing into the smoke. I’d hear the pak-pak-pak of branches, and remember the pak-pak-pak of the lice cooking in the steam.”

The other brother, Dov, was equally descriptive in chapters in which they alternated telling their stories to an unnamed interlocutor.

Besides experiencing the concentration camps, we follow the brothers as they barely survive a death march; understand how confusing the liberation of the concentration camps by Allied forces were to prisoners whose thoughts had been mainly restricted to where the next piece of bread would come from; go through the recuperation process in the refugee camps; are disappointed with the brothers as they visit their former homes and friends in their native land of Czechoslovakia; and empathize with the refugees’ disorientated feelings in Israel, where they neither speak the language nor fully comprehend that they are free, living with other Jews who will protect them, not harm them.

Being quite long, this book requires a time commitment and a willingness to experience vicariously some very deep emotions. It is a primer on the Holocaust that few readers will forget.

*

Donald H. Harrison is editor of San Diego Jewish World. He may be contacted via donald.harrison@sdjewishworld.com