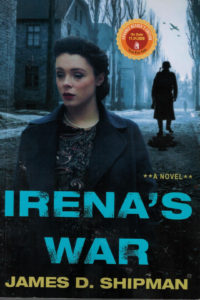

Irena’s War by James B. Shipman; Kensington Books, 2020; ISBN 9781496-723888; 360 pages plus author’s notes and discussion questions; to be distributed in December; $15.95

SAN DIEGO – The story of the late Irena Sendler, who is credited with saving the lives of as many as 2,500 Jewish children, is already well known. She was honored by Yad Vashem Holocaust Museum in Jerusalem as a Righteous Gentile more than 50 years ago. Books and movies have been written about her, with more to come, including one in which Israeli actress Gal Gadot, known as “Wonder Woman” to movie goers, has been signed to portray her.

SAN DIEGO – The story of the late Irena Sendler, who is credited with saving the lives of as many as 2,500 Jewish children, is already well known. She was honored by Yad Vashem Holocaust Museum in Jerusalem as a Righteous Gentile more than 50 years ago. Books and movies have been written about her, with more to come, including one in which Israeli actress Gal Gadot, known as “Wonder Woman” to movie goers, has been signed to portray her.

In this novel by James D. Shipman, we meet an Irena drawn from both the historical record and Shipman’s imagination. Some of the characters are real, but Irena’s chief antagonist, a Gestapo major called Klaus Rein, is fictional. The plot and timing of some events vary from more historical accounts, such as the one found on Wikipedia. So, it’s best to read Irena’s War as a suspense novel, rather than as accurate history.

In brief, Sendler worked for a German-sanctioned Polish social services agency that provided food rations to Poles outside the Warsaw Ghetto and disease control for the Jews inside the ghetto. Sendler had herself transferred from the food relief section, in which she had tried to bring aid to Jews as well as Poles, to the disease control section which provided her with a pass to go in and out of the ghetto.

Shipman’s story tells of Sendler’s success in obtaining forged papers for the Jewish children, giving them Christian names and Polish identities, and working with members of the Resistance both inside and outside the ghetto to smuggle the children to churches and other various places of refuge around Warsaw and the Polish countryside. Knowing that if the children’s parents ever were able to return from the Treblinka Concentration Camp, or other Nazi death factories, she kept a record of each Jewish child’s original name, Christian name, and the family, or place, to which their lives were entrusted. These lists she put in jars and buried in the ground in the mostly unrealized expectation that someday family reunification could be achieved.

In the novel, Sendler is presented as a heroic, yet flawed, idealist. She and her husband have long been separated and she carried on an affair with a Jewish lover, who likewise was separated from his spouse. Her relationship with her mother was tense. But her determination to save as many children as possible, and not to divulge the names of her contacts in the Resistance, was monumental.

Author Shipman has us follow Sendler into interrogation rooms with the Gestapo and clandestine meetings with the Resistance. We slog with her through the muck of the sewers through which many of the children escaped the ghetto. We are with her when she is tortured by the Gestapo, and when her life is saved by a bribed prison guard. We feel the passion of her relationship with her Jewish lover, Aaron, who, like her, believes in vain that socialism or communism will bring peace and equality to a waiting world.

So, even though we know from actual history that Irena will survive the Nazi period, the twists and turns that led to her survival – some of them historic, some of them fictional – keep us turning the pages.

*

Donald H. Harrison is editor of San Diego Jewish World. He may be contacted via donald.harrison@sdjewishworld.com