MEVASSERET ZION, Israel — In 1928 Herbert van Son, the uncle I never knew, was a young man of nineteen. The family lived in Hamburg and his father was a successful importer of tobacco. He arranged for his son to travel to Louisville and work as an apprentice to a business associate who was a tobacco farmer and trader there. He writes about the hot, damp climate and the warm relations between him and his employer, who helped him get settled and even took him to the Kentucky Derby. It was all interesting but very different to the life he had known in Hamburg,

MEVASSERET ZION, Israel — In 1928 Herbert van Son, the uncle I never knew, was a young man of nineteen. The family lived in Hamburg and his father was a successful importer of tobacco. He arranged for his son to travel to Louisville and work as an apprentice to a business associate who was a tobacco farmer and trader there. He writes about the hot, damp climate and the warm relations between him and his employer, who helped him get settled and even took him to the Kentucky Derby. It was all interesting but very different to the life he had known in Hamburg,

Herbert, like most of the members of his family, was an inveterate letter-writer. Every week a typed letter describing his experiences and encounters in Louisville’s tobacco farming and processing industry would arrive in the family home in Hamburg. His initial tentative steps in the field eventually led to his being given ever more responsible positions, such as improving the speed and efficiency with which the blending process was managed. He writes home that “All the Negroes here regard me as the ‘Big German Boss,’ simply because I don’t talk to them as if they were dogs, and I don’t go around with a gun in my pocket, like the other managers do, indicating their ridiculous arrogance and stupidity…”

After spending a year in Louisville and the surrounding area, Herbert was asked to manage the Chinese branch of the American tobacco company to which he had been apprenticed. After a brief trip back to Hamburg to see his family, he set off overland to Shanghai, taking a series of trains culminating in a week-long journey on the Trans-Siberia express. Before leaving Hamburg he traced his route with his younger brother, Manfred, who eventually became my father.

Herbert’s letters, which were written in German, were carefully collected and filed by his parents, and that file was among the few possessions my late father was able to take out of Germany when he fled the country in December 1938, after Kristallnacht.

There are no letters from Herbert from Shanghai. The family was informed a few days after his arrival of his death there by suicide, and the anguished correspondence between his father and the Jewish community there regarding the gravestone is all that remains.

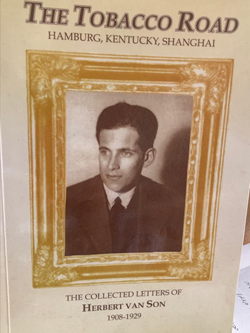

In 2002 my father commissioned the translation of the letters, which I undertook together with Miriam Ron. The letters, which were published in book form as The Tobacco Road; Hamburg, Kentucky, Shanghai, trace the brief trajectory of Herbert van Son’s life.

Several years later, I spent some time in the British Library’s Newspaper Department in Stanmore, London, as my father was sure that there had been a newspaper report of the incident. Lo and behold, in the May 25 edition of the North China Herald, the English-language weekly newspaper that appeared in Shanghai at the time, I came across an it em headed ‘Tragedy in a Bathroom; Young Foreigner Found Dead: Suggested Suicide.’ My sharp intake of breath when I found it caused heads to turn, but blessed silence was soon restored.

I thought of my uncle when I read about the demonstrations and unrest following the decision not to prosecute any policemen for the death of Brionna Taylor in Louisville. Whenever I hear the name of that city, I think of the bright young man who came to a tragic end at the other side of the world.

*

Dorothe Shefer-Vanson is a freelance writer based in the Jerusalem suburb of Mevasseret Zion, Israel. She may be contacted via dorothea.shefer@sdjewishworld.com