SAN DIEGO — I’ve never known a bad guy named Sam. I said that in the early 1960s, and many years later it is still true. Sam’s are warmhearted with a faint, off-beat nature. They are comfortable with their lives, competent in their work, devoted husbands that don’t cheat on their spouses; they usually work for large organizations and don’t complain.

My observation of these people inspired me to design and build a nine-foot tall stucco sculpture for Helen and Mike and named “The Essence of Sammy.”

Mike prepared my income tax. His company name wa s“Mail Me Monday,” a catchy moniker for the bookkeeping portion of his business. Helen was his secretary. They were both in their late 50s. The business flourished and they bought a stately, light gray, stucco home nestled comfortably among tall trees and foliage in a lovely residential area. In the rear of their large property, Mike tended plump magenta fuchsias that sagged so much from the weight of their bloom you could hear them groan. He also planted and raised plush, emerald, green-leafed trees from, which hung softball-size lemons. They looked like Christmas trees with enormous yellow ornaments. In the front of the house was a a tall row of hedges surrounding a small lawn area, that could only be seen through the kitchen window. They thought the lawn, with its privacy. would be the perfect setting for a freestanding sculpture. Helen like the idea of gazing out the window at the sculpture while she prepared the meals

Mike was the spitting image, and same wry persona, as George S. Kaufman, the renowned humorist and playwright. My unkempt records were a test of his humor and customer relations skills. He kept his sanity, during my appointment, with an appreciation of “How anyone could be so disorganized and vague-yet poetic in their paper work.” “Mine were not records,” he crooned, “more like a collection.”

Helen, with blended, sandy gray hair, was quiet, steady as a rock, and initially harder for me to know. She was bright, and educated, with an inherent common sense and wisdom. It served her well in being a loyal spouse, raising three children, and observing and interpreting the events of her life. She was a classy, cultured woman to all who knew her.

After two years years of doing my taxes, they commissioned me to create the sculpture for their garden. They liked abstract art, which surprised me. I usually associated “older” people with more traditional taste. However, these were not ordinary people. I sculpted a clay model, which I proudly showed them, it was an abstract depiction of a proud, whimsical figure. They were excited about the creation, enjoying its humor and warmth, and praised it with enthusiastic comments.

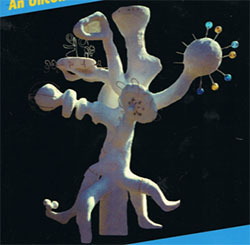

“How big?” Mike said. I thought about nine feet tall. It would be constructed from white cement stucco, over a steel-rod and iron-mesh armature. Details in copper and steel would project from the internal structure, inlays of mosaic tile accompanied by inscribed designs would be decorative where needed. To add to the fun, colored fish float balls, in blue and gold, would protrude from a globe at the end of one of its six arms. A final inspiration was the balancing of three stucco balls on the end of one of Sammy’s six legs.

Excited by their approval and cash deposit, I began construction. It took a week to shape and weld the half-inch-thick rod together cut, shape, and tie the mesh to it. My assistant was Santosh Rana, a 21-year-old student attending San Diego State. He helped me in various projects. Santosh was of royal blood. He was the grandson of the deposed King of Nepal. He lived in Del Mar with his brother and sister-in-law. Olive skinned, he was built like a delicate flower and walked like a gazelle. Medium height with a slight, but wiry build, the most gentle of men, and a beautiful sensitive soul. I enjoyed watching him work, serenely smoking a pipe, wearing a richly patterned, Nepalese rust colored peaked cap perched on his brown head like Nehru. The Himalayas were brought to my shop.

Santosh had one fault-he was accident prone. He was constantly cutting himself or falling over objects. Once I had to rush him to the doctor to stitch a badly cut finger. When we applied the scratch coat of stucco to Sammy’s metal frame, he mixed the cement. I gave him instructions on the proper proportions of sand, cement, and water. It took eight hours of hard work for me to apply the coat with a trowel and sponge. When it was done, I was thrilled at the form it had taken.

We went home, tired but satisfied from our labor. The next morning, something was wrong. The cement was not dry and hard as it should have been. It was as green, moist, and soft as when we had left it the night before. Suspicious, I asked Santosh what mix he had used in making the cement. To my amazement, he had reversed the formula and used only one-third of the amount of cement required. He was as devastated as I was and offered to work for free and pay for what he had done. I declined and we spent the next several hours removing and disposing of the bogus stucco. Thereafter, I kept a keen eye on his mixing, and there were no more problems.

Sammy was finished in a month. I was absolutely thrilled at my creation, and excitedly looked forward to seeing it in place. The task now was to hire a crane to lift the 900 pound sculpture onto a flat bed trailer hitched to my pickup truck and transport it carefully sixteen miles to the Lustig home. Buzz, a 69-year-old, gruff, metal-pounder I knew, had an old crane. He would do it for twenty bucks. When he arrived and saw Sammy for the first time, he burst out laughing and made some caustic comments. He had never seen anything quite like it. He climbed a ladder, placed a sturdy hook from the ancient crane onto the steel eye hidden in Sammy’s crown, and hoisted it onto the trailer. Sammy and I cruised proudly down the freeway to the amused and curious eyes of passengers in cars driving alongside us. The Lustigs were not at home when the sculpture was lifted onto the lawn. They were busy at work and would see it later in the evening. I was pleased at how Sammy seemed to be a natural part of the surroundings, hugged by the trees and foliage around him. I went home and couldn’t wait to get the congratulating phone call from Helen and Mike.

The next morning, Mike called. He said he’d like to meet me for lunch. Over a salami on rye he gently said, “Ira, I like Sammy very much, but my wife has a problem with him. She feels that he is too big and overpowering for her. She went to bed last night, after an evening of looking at him from her kitchen, and had nightmares. I’m going to pay you for your creation, and I want you to find some institution that will take him, so I can claim a tax-deductible donation. In the meantime, take Sammy back to your shop so my wife will be happy. I will pay for the crane to remove it,”

I was heartbroken, as was Sammy, who loved his new home. I called an incredulous, laughing Buzz, who lifted a disappointed Sammy off the trailer for another twenty bucks.

I told the story to an architect client of mine. He also happened to be the architect for United States International University, a school in its expansion period at the time. He said, “ We can use Sammy in the center court of the new arts building I designed. The president will be pleased that we can get it for free. The building won’t be finished until December, but you can bring it to the construction site and store it behind the maintenance building until the courtyard where it will be placed is finished.” I reported this to a pleased Mike. Once again I called the sardonic Buzz and handed him another twenty bucks.

Months went by before the president of the university went behind the maintenance building to see Sammy for the first time. He took one look, phoned the architect, and said, “Out!” An embarrassed phone call told me the news. Heart broken, I made the now all-too=familiar trip down the freeway. A local tow truck lifted an equally dejected sculpture onto the trailer. Ahead of his time, Sammy knew what it was to be homeless-sculpture wise. Screw Buzz and his twenty bucks.

During this period, I was involved in an organization located in a gorgeous, landscaped setting. It was formerly a luxury hotel for the friends and relatives of homeowners in one of the wealthiest communities in the United States. Bob Driver, Sr., a very successful insurance man, had purchased the hotel for his son Bob, Jr., to use for a personal growth center, in vogue at the time. I told Bob about the fortunes of my creation and the slings and arrows hurled my way. An always nurturing Bob suggested that Sammy be brought to his lovely grounds and, “In this caring setting he would be cherished and admired and his self-esteem restored.”

For the last time I called Buzz. By this time, he passed the rubicon of sarcasm and had grown quite fond of Sammy. He delivered and set the sculpture in a beautiful spot in the gardens. Buzz even bought me a drink at the bar where we reminisced about Sammy and other work he had done for me as well. It was only right that he bought me the drink, with all the twenty-buck deals we made. It had become an annuity.

In 1972, my family and I moved to the woods of eastern Pennsylvania for a short five months. When we returned, the whole world had turned upside down. Bob, Jr. was dead at the age of 35 from leukemia. His widow, Patty, moved the growth center to a shopping center. The property was sold and subdivided into residential lots. “Sammy?” He wound up in the front yard of the house of Bob’s younger brother.

*

Ira Spector is a freelance writer based in San Diego. This selection, with slight revisions, was republished from Spector’s 2011 work, Sammy Where Are You? An Unconventional Memoir … Sort of. It is available via Amazon.