By Donald H. Harrison

SAN DIEGO — Chris Jennewein, editor and publisher of the Times of San Diego, wrote a column on Saturday, which suggests that rather than turning back undocumented migrants who have braved hardship to come to the United States, we should welcome many of them.

SAN DIEGO — Chris Jennewein, editor and publisher of the Times of San Diego, wrote a column on Saturday, which suggests that rather than turning back undocumented migrants who have braved hardship to come to the United States, we should welcome many of them.

Jennewein argues that young immigrants bring energy, entrepreneurship, and willingness to work hard — all necessary stimulants for a U.S. economy that is challenged by an aging population and competition from the autocratic regimes of Russia and China.

He notes that some people call for a “selection process to ensure that immigrants are educated and have resources. But there’s already a rigorous selection involved in mustering the courage to leave everything behind. The best and the brightest are always risk takers.”

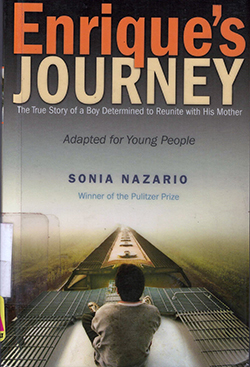

By coincidence, the day Jennewein’s column was published, I finished reading Enrique’s Journey, a 2006 compendium of Pulitzer Prize winning articles written in 2002 by Sonia Nazario about the life of a Honduran boy who was 5 when his single mother, Lourdes, left home to be smuggled into the United States.

I obtained a copy of the book from the San Diego Public Library after a short time on its waiting list. The library sent to me an edition “adapted for young people,” but it was vivid enough for me to appreciate what Enrique had lived through. I was impressed by Nazario’s journalistic talent.

Lourdes’ income from selling gum, crackers and cigarettes from a door step never was sufficient to feed her family. She hoped to earn sufficient money in the United States to provide for Enrique and his older sister, Belky, and then return to their home near Tegucigalpa, the capital of Honduras. However, Lourdes never earned sufficient money; she barely got by in the United States, working at low paying jobs, first in Los Angeles County and later in North Carolina.

Back in Honduras, as Enrique grew, he had a tangle of emotions. He loved his mother from afar, and appreciated the small gifts and money she mailed back to her children, who stayed with relatives. But he also resented her for leaving, a resentment that boiled over into anger, self-pity and self-destructive behavior. He sniffed glue, smoked marijuana, and drank alcohol to excess.

Nevertheless Enrique was a hard worker, and he had the bravery and determination that Jennewein writes about. At the age of 17, he decided if his mother could not come back to Honduras, he would find her in the United States. And so he set out on his journey. On seven different occasions, he was stopped in Mexico and sent back. Sometimes he was robbed and beaten; two teeth were broken, one eye was damaged, and yet he persevered.

On his eighth try, after a harrowing ride atop a freight train, where he had to brave the heat of the desert and the chill of the mountains he made his way northward, always on the lookout for gang members who might kill him for the few possessions he carried with him, and immigration police — la migra — who would arrest him and send him back to Guatemala on Mexico’s southern border. Hungry, parched with thirst, sleepless, he would get off the train here and there, beg for food and water, and try to find safe places to sleep, including cemeteries.

At checkpoints where discovery would lead to deportation, he would get off the train and wade through bush and bramble to avoid Mexican immigration authorities, but these places also were where local gang members waited to prey on the migrants. With seven unsuccessful tries under his belt, Enrique was able to better anticipate potential problems along the route than some other migrants. Many migrants were murdered along the same route, and others, after suffering robberies and beatings, turned back in defeat for home.

Finally, Enrique reached Nuevo Lardeo, Mexico, and after languishing there for a while, attempted successfully to cross the Rio Grande River to Texas. Not being able to swim, he held onto an inner tube for dear life. Once in the United States, he connected with U.S.-members of a smuggling ring, who drove him to Orlando, Florida. There, he was met by his mother’s boyfriend, who took him the rest of the way to her trailer home in North Carolina.

However, Enrique’s journey was not only a physical one; it was also psychological. Although he loved his mother, he still resented her; how different his life would have been if she had stayed at home, he thought. So their relationship was quite tense. He acted out, continued drinking, and carousing after work.

He had left behind a pregnant girlfriend, Maria Isabel, meaning unless he did something different from his mother, the cycle of abandonment would repeat.. As several years went by, Enrique mellowed, wanting to do better by his child than he felt his mother had done by him. He worked, he sent money to Maria Isabel, he talked to her and their daughter Jasmin by telephone, and he plotted family reunification. First Maria Isabel was smuggled into the United States, and later Jasmin was brought by relatives to Florida, to which Lourdes, Enrique and family had relocated in the interim.

Gradually, Enrique forgave his mother, for he saw how hard it was for her to not only pay her own living expenses, but also to pay off the smugglers who had enabled Enrique to get to the United States. Now Enrique had a similar debt, which he worked seven days a week in an effort to retire. At last, however, the family was together, everyone working, peace and serenity restored.

And then Enrique was arrested on a warrant for driving without a license. Sheriff’s deputies turn him over to U.S. Immigration authorities, who began proceedings to have him deported. (And that is where the narrative ended, but in follow-up stories we learned from Nazario that Enrique was able to resume his life in Florida as a house painter, but that he and Maria Isabel divorced.)

What often is lost in the debate about immigration is the human element. When we read news stories that tell in denominations of thousands how many people were apprehended at the border, how many were turned back, how many were sent to children’s shelters, and how many families were allowed by U.S. authorities to travel onto their relatives, we may lose sight of the fact that each number within this set of statistics represents a real person — a person with hopes and dreams and problems.

Enrique, Lourdes, Maria Isabel and Jasmin are examples of the individuality of the immigrants, but they are not prototypes. Because just as you and I, as Americans, have different life stories, so too do each of the immigrants who risk life and limb for the chance to live here in America, where Lady Liberty still promises to “lift my lamp beside the golden door!”

*

Donald H. Harrison is editor of San Diego Jewish World. He may be contacted via donald.harrison@sdjewishworld.com