By Rabbi Dr. Israel Drazin

BOCA RATON, Florida — Giovanni Boccaccio (1313-1375) authored The Decameron around 1348, a word meaning “ten days,” referring to the activities described in the book. The book’s subtitle Prencipe Galeotto refers to the legendary friend of Lancelot, an enemy of King Arthur. He helped Lancelot seduce and bed Arthur’s wife Guinevere. The subtitle catches the theme found frequently in the book of tricks played on unworthy men, usually husbands, and of lonely women who were confined in their homes in the 14th century by their spouse and fathers while longing for sex, while men engaged in a fun-filled life which included bouts of drinking and forbidden sex.

BOCA RATON, Florida — Giovanni Boccaccio (1313-1375) authored The Decameron around 1348, a word meaning “ten days,” referring to the activities described in the book. The book’s subtitle Prencipe Galeotto refers to the legendary friend of Lancelot, an enemy of King Arthur. He helped Lancelot seduce and bed Arthur’s wife Guinevere. The subtitle catches the theme found frequently in the book of tricks played on unworthy men, usually husbands, and of lonely women who were confined in their homes in the 14th century by their spouse and fathers while longing for sex, while men engaged in a fun-filled life which included bouts of drinking and forbidden sex.

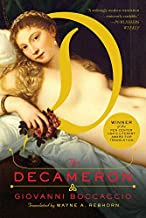

There are many translations of Boccaccio’s classic. All that I saw translates the Italian into outdated English which is no fun to read. I enjoyed the 2013 translation by Wayne A. Rebhorn. His book is very readable. He also introduces the Decameron with 65 pages of information about the time of the writing, the author, what he wanted to accomplish, and more. He also has 81 pages of notes at the end of the book as well as infrequent notes on the page of the stories themselves.

The book tells about the Black Death of 1348, which some scholars estimate killed some 60,000 people in and around plague-ridden Florence, Italy. Seven women and three men – significant numbers in Judaism and Christianity – escape the city and go to a villa in the countryside for two weeks. During ten days, each of the ten tells a tale, sometimes no longer than several pages, virtually all very interesting, involving unusual even surprising behavior, and humorous. On eight of the ten days each must relate a story on an assigned topic such as people who suffered misfortunes arriving at a happy unexpected time, individuals who cleverly acquired something they desired or had lost, and women who tricked their husband to gain sex from another man. All told, there are 100 narratives in the book. Day seven, for example has ten tales where wives cleverly outwit their husband, hid their adulterous escapade and their paramour, and create a situation where they can continue to have illicit sex without their husband’s meddling. Day one has two concerning Jews. The following are examples of three of the 100 yarns.

Day seven’s five-page second romance is about a wife who has been having sex with her lover whenever her husband is absent. One day he comes home unexpectedly. She tells her lover to jump into a barrel. She goes out of the bedroom and greets her husband who tells her he just sold the barrel for five ducats. Being quick witted, she tells him that while he was gone, she sold it for seven ducats and the buyer is examining the barrel now. The lover hears the conversation and climbs out of the barrel. When the husband and wife enter the room, the lover complains that the barrel is not entirely clean. The wife says, no problem, my husband can climb into it and clean it. The husband does so. While he is cleaning the inside of the barrel the wife leans over to watch him, covering the opening and making it impossible for her husband to see outside the barrel, and the lover approaches the wife from behind and has sex with her. When the husband finishes the cleaning, his wife and her lover require him to carry the barrel to the lover’s home.

The two narratives involving Jews occur in day one.

The third three-page saga concerns a smart Jew who tells Saladin about three rings to avoid a trap set for him by the Sultan. Saladin asked him to say which of three religions – Jewish. Saracen, or Christian – is the true religion. The Jew said the answer is found in a decision of a loving father. A wealthy man had a precious ring. He announced that he will give it to one of his sons. The son who has the ring should be considered his heir and others should honor him as the head of the family. The son who received the ring did as his father, and the ring passed down through many succeeding generations until it came to a man who had three sons. He loved all three. So he had a master craftsman secretly make two other rings so similar that no one could identify the true one. When he was dying, the father gave each son a ring in private. After he died, each showed his ring and claimed the inheritance and title. But when they realized that the rings were so similar that they could not tell which was the true one, the question of which one was their father’s true heir was left pending. Then the Jew said to Saladin, it is the same with God’s law, the question of who is right is still pending. Saladin was impressed by the wisdom of the Jew and the two became lifelong friends.

This legend unquestionably portrays Jews in a favorable manner. In contrast, some readers might claim that the five-page second account in day one portrays the Jews as fools.

A Christian badgered a Jew to convert. After being so often entreated, the Jew agreed to consider conversion after he would visit Rome and see the behavior of the Pope and clergy. The Jew traveled to Rome and found the Christian religious leadership to be corrupt, immoral, gluttonous, fraudulent, hypocritical, lustful, raping male children, rarely sober, and never overlooking a single sin. He concluded that the Pope and clergy were using their skills to drive Christianity from the world. When he returned home, the Jew told his Christian friend what he saw and concluded that this decided him to convert. His friend was surprised and asked him why he made this decision after seeing how the church leaders debased Christianity. The Jew answered: Since I saw that despite their behavior, Christianity is “constantly growing and becoming more resplendent and illustrious, I think I’m right to conclude that the Holy Spirit must indeed be its foundation and support.” Therefore, I will convert. And he did so.

Now, it is obvious that the Jew’s logic is absurd. Should we conclude that Boccaccio was mocking Judaism? Perhaps. But it is also probable and perhaps even more likely, that Boccaccio was criticizing the Christian clergy in this fable as he does in others, and does so with this humorous silly account.

*

Rabbi Dr. Israel Drazin is a retired brigadier general in the U.S. Army chaplain corps and the author of more than 50 books.