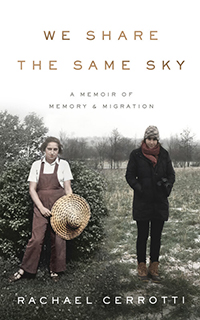

We Share The Same Sky: A Memoir of Memory & Migration by Rachael Cerrotti; Blackstone Publishing, 2021; ISBN 9781094-153728; 236 pages plus 10 pages of photographs.

By Donald H. Harrison

SAN DIEGO –When Sergiusz Scheller left his home in Poland to move to America to be with his bride, Rachael Cerrotti, his mother Danuta told him, “We share the same sky. We look at the same stars. So we are close.”

SAN DIEGO –When Sergiusz Scheller left his home in Poland to move to America to be with his bride, Rachael Cerrotti, his mother Danuta told him, “We share the same sky. We look at the same stars. So we are close.”

Although the title of this memoir takes its name from that exchange, Cerrotti’s book is only partially about her husband, who left her a widow while still in her late 20s. The bulk of the book is about Rachael’s grandmother Hana, who as a young teenager during the Nazi era was sent by her parents from Czechoslovakia to safety in Denmark, where for a while at least she could live unmolested as a farm girl. When Denmark’s German Nazi conquerors decided to round up the Jews, she was among the thousands who were helped by the Danes to escape to neutral Sweden. From there, after the war, she eventually made her way to the United States, where she was shocked to learn that the relatives who sponsored her in Cincinnati were prejudiced against Black people — even one who had assisted her during her travels. She and the relatives soon parted ways.

Rachael Cerrotti, whose mother was Jewish and whose father was a Christian minister who had converted to Judaism, interviewed her grandmother about her life in Europe, on the run from the Nazis, and about her eventual immigration to the United States. Rachael often focused on Hana’s resourcefulness, willingness to work hard, and her ability to thrive on her own.

Eventually, Cerrotti, a photographer and blogger with an adventurous soul, decided to follow in her grandmother’s footsteps, living in the cities where she lived, following the routes that she took from one part of Europe to another, and utilizing her grandmother’s diaries as travel bibles. The result was a double-edged narrative: in this book, Cerrotti alternates Hana’s World War II story while a single woman with her own journalistic journey.

We meet people whose lives crossed paths with Hana’s, including Rabbi Bent Melchior of Copenhagen, who as a child escaped in the same fishing boat that surreptitiously carried Hana and his own family to the shores of Sweden. Despite their age difference, the rabbi and Cerrotti became good friends. So too did she establish contact, and friendship, with the Swedish family that spotted Hana on the shore and took her in. Cerrotti and the subsequent generations of that Swedish family bonded over their shared historical heritage.

Cerrotti and Scheller had met years earlier when they were international students at the Hebrew University in Jerusalem. Off and on, they had traveled together, became intimate with each other, and eventually realized that they had fallen deeply in love. So, the Jewish American and the Polish Catholic decided to have an international wedding ceremony, cheered on by Protestant Danes and Swedes.

This is both a Holocaust story and a travelogue, more so the latter than the former. While Hana lost the family that she left behind in Czechoslovakia, she, herself, had been in comparative minimal danger. But she had to withstand loss, the survivor’s guilt, and profound grief, just as her granddaughter Rachael later would feel tremendous grief after a heart attack felled her young husband.

Experiencing that grief made Cerrotti realize that she had not completely understood Hana’s story; yes, she had gone to the same places, and had met some of the same families, but she did not experience the same emotions. After Scheller died, Cerrotti felt compelled to retrace her grandmother’s route, in an introspective effort to feel — and understand — what Hana had experienced.

Although their experiences as single travelers in Europe were some 70 years apart, Cerrotti had an abiding gift of empathy, especially for current-day young migrants from the Middle East, who like her grandmother, traveled to a European country where they knew no one, and were familiar with neither the language nor the local customs.

If Cerrotti’s life story had been set in the American Southwest, instead of in Northern Europe, one assumes she would have felt the same deep empathy for the young Central American migrants who cross alone into the United States.

*

Donald H. Harrison is editor of San Diego Jewish World. He may be contacted via donald.harrison@sdjewishworld.com