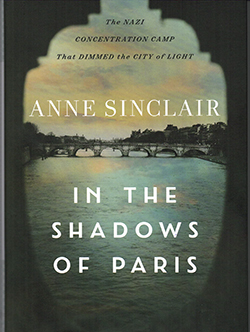

In the Shadow of Paris: The Nazi Concentration Camp That Dimmed the City of Light by Anne Sinclair; San Diego: Kales Press (c) 2021; ISBN 9781733-3g5761; 117 pages including notes and bibliography.

SAN DIEGO — French journalist Anne Sinclair confesses she had long felt guilty about not asking her late paternal grandfather Léonce Schwartz to tell her about his internment at a little-known concentration camp on the outskirts of Paris. Known by the French as the Royallieu-Compiegne Concentration Camp, and by the Nazi Germans as Frontstalag 122, it was not as well-known as Drancy, the notorious French transit point to the Nazi killing camps in Poland. However, the prisoners there were treated just as callously. Starvation, lice, frostbite were common ailments purposely neglected by the Nazis in their effort to humiliate and winnow the French Jewish population.

SAN DIEGO — French journalist Anne Sinclair confesses she had long felt guilty about not asking her late paternal grandfather Léonce Schwartz to tell her about his internment at a little-known concentration camp on the outskirts of Paris. Known by the French as the Royallieu-Compiegne Concentration Camp, and by the Nazi Germans as Frontstalag 122, it was not as well-known as Drancy, the notorious French transit point to the Nazi killing camps in Poland. However, the prisoners there were treated just as callously. Starvation, lice, frostbite were common ailments purposely neglected by the Nazis in their effort to humiliate and winnow the French Jewish population.

So, Sinclair set about learning as much as she could about the camp, hoping futilely to find direct commentary about her grandfather in the memoirs written by other Jews who had been rounded up by the Germans in a December 1941 pre-emptive strike against those who had been intellectual or political leaders or, like her grandfather, noteworthy business leaders.

So, Sinclair set about learning as much as she could about the camp, hoping futilely to find direct commentary about her grandfather in the memoirs written by other Jews who had been rounded up by the Germans in a December 1941 pre-emptive strike against those who had been intellectual or political leaders or, like her grandfather, noteworthy business leaders.

What she did find amid all the stories of misery in the camp were uplifting references to some Jews organizing lectures to keep their minds and those of their fellow prisoners active, and other Jews, notwithstanding their deteriorating conditions, helping those who were weaker than they.

“Louis Engelmann gives a class on electricity; René Blum [brother of former French Premier Leon Blum] speaks about the French men of letters Alphonse Allais, Tristan Bernard, and Georges Courteline; Jean-Jacques Bernard talks about the theater and French poetry of the Middle Ages; André Ullmo, about the greatest trials in the Court of Justice; Jacques Ancel about the concept of nations,” Sinclair wrote.

Debates in the concentration camp were common among Jews as to their real identities. Some held fast to their Jewish religious identity, especially those who had moved to France from other European countries, whereas many native-born French Jews considered themselves French citizens and patriots first, and Jewish a distant second, if at all, so assimilated had their families become. Of course, this made little difference to their Nazi captors, who considered all Jews to be nothing more than an undifferentiated mass of untermenschen (sub-humans), unfit to breathe the same air as Aryans.

Because he was sick, and the Nazis’ “final solution” to murder as many Jews as possible was not yet well-understood by the rank and file, Jews who were too young, too old, or in Schwartz’s case, too ill, to be sent to “work camps” in the East, were allowed after three months at Frontstalag 122 to return to their homes. Grandfather Schwartz immediately thereafter went into hiding until the end of World War II.

*

Donald H. Harrison is editor of San Diego Jewish World. He may be contacted via donald.harrison@sdjewishworld.com