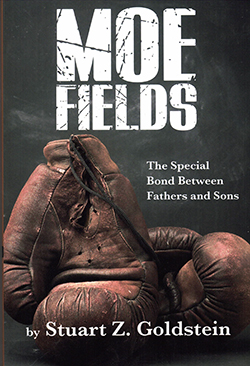

Moe Fields: The Special Bond Between Fathers and Sons by Stuart Z. Goldstein; New York: Pen Paper Press (c) 2020; ISBN 9781736-632208; 378 pages.

Moe Fields: The Special Bond Between Fathers and Sons by Stuart Z. Goldstein; New York: Pen Paper Press (c) 2020; ISBN 9781736-632208; 378 pages.

SAN DIEGO — This is a powerful book, a disguised memoir in the form of a novel, about a man who fought and loved fiercely, and the impact he had on the lives of his three sons. It seems obvious from the brief biographical sketch of author Stuart Z. Goldstein at the end of the book that he is the model for Zachary, Son Number Two of the fictitious Murray Goldman, who boxed under the name of “Moe Fields.”

Goldman, who grew up in the Depression, used to fight at a neighborhood club to pick up an extra $10 or $20 to help out his impoverished family. He identified himself with a pseudonym because he knew his religious father would disapprove of the violence and physical risk- taking. An important moment in his early career came after taking a shellacking by his opponent. He conquered his fear of suffering more pain and went back into the ring to fight some more, going on to win. Later, as an enlisted man during World War II, his resolve in the face of danger helped to save his Navy ship from sinking. He wasn’t well educated with book learning, but he had a moral compass and tremendous integrity. In the post war, he built a successful plumbing business only to have it bankrupted resulting from the time he needed to recuperate from a brain tumor and a horrendous traffic accident that crippled his wife, Franny, Goldman was not the sort of person to bemoan his fate nor to worry about a loss of status. After his business failed, the man who once was a generous contributor to the Jewish community of Paramus, New Jersey, labored for near minimum wage as a uniformed security guard until he could start up his business anew. Murray never felt sorry for himself.

The three sons were inspired by Murray’s resolve, his work ethic, and the great love he had for their mother, who, while growing up in the Depression, could defeat any man — including Murray– at handball, and played a mean saxophone. Each son, in his own way, tried to emulate Murray’s toughness and determination.

Antisemitism and interracial relations are a recurring theme in this book. Perhaps because family members suffered antisemitism, they spurned bigots with racial prejudices. Before he was married, Murray had an African-American lover. So did Zachary. African-American and Haitian caretakers looked after the family in the wake of accidents and hospital stays. The Goldmans thought for themselves, made their own decisions regardless of social pressures, and had great capacities for love.

If other men who read this book are like me, they’ll find themselves reflecting on their own relationships with their fathers as well as with their sons. While Murray didn’t care for his father’s gambling, which often left the family without financial resources, he still loved and honored him. As a father, his work as a plumber often kept him away from watching his boys’ accomplishments at school and at extracurricular activities, but he nevertheless was able to communicate to them how very proud he was. Murray was a man of few words, big hands, and a bigger heart.

As you read this chronicle of Murray’s life and of those of the three sons — Alan, Zach, and Gary — you probably will feel yourself being drawn to this idealized portrait of love and sacrifice. A disclaimer at the front of the book was interesting. “Moe Fields is a true story. However, in fairness, what’s true in life (or non-fiction narrative) is often a matter of perspective. The author does not claim sole ownership of the truth. Each of us in my family may have experienced these life events differently.”

*

Donald H. Harrison is editor of San Diego Jewish World. He may be contacted via donald.harrison@sdjewishworld.com