By Ari Volvovsky

As told in Hebrew to Toby Klein Greenwald

EFRAT, Israel — It was Chanuka, 1986.

I had arrived at the Gorky Prison in June. In September I was sentenced to three years of hard labor. As the time drew close for my appeal, to be held in Moscow, Chanuka also drew near.

I had been judged guilty of “the distribution of lies and false reports against the Soviet regime,” but what was meant by “lies and false reports,” nobody knew. I had passed around to friends that notorious book by Leon Uris, Exodus, and the police claimed that they found something in the book that was anti-Soviet. Furthermore, I had invited friends to a Passover seder in our home. I had compared Egypt to the Soviet regime.

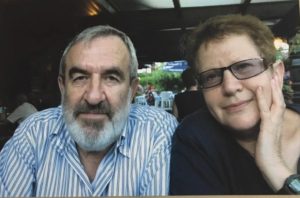

Mila, my wife, says I was a free man in a country that was not free. I openly wore a kipa (skullcap) with a star of David. I taught Hebrew, which was not formally an illegal act.

I was sent to the Gorky prison, an enormous complex with 15,000 inmates. The authorities were afraid I would influence others, so I was placed with three non-Jewish prisoners, each of whom was afraid that the others would inform on him.

From the moment I entered prison, I told all my cellmates that I was a Jew. I explained to them some general rules of my religious behavior, such as my adherence to keeping kosher. They accepted it with understanding. I spoke about the land of Israel, about Torah and about the Jewish people. At first, they just listened. Then they began to ask questions about the Bible and Israel. I felt that because I was not afraid to speak of my Jewishness, they accepted and respected me. I never experienced anti-Semitism from fellow prisoners.

As Chanuka drew near, these three gentiles sat with me and listened as I told them the story of Chanuka and described the laws and customs we practice. They said, “We want to celebrate Chanuka with you. How will we do it? I explained that we need oil or candles.

An electric light burned twenty-four hours a day in our cell. We were required to follow a strict daily schedule, allowed to do nothing out of the ordinary, and go to sleep at ten o’clock.

All the wardens were women and they were unusually cruel. Nevertheless, I said to my fellow cellmates, “We must go ahead with our plan. We must celebrate Chanuka.”

Among the wardens was an old lady who was slightly less cruel than the others. About a week before the holiday, I said, “Friends, we will somehow obtain oil.” Nobody believed me. I said, “God wants us to do it. Just wait and see what I do.”

I knocked on the door. The elderly warden looked in and barked cruelly, “What do you want?” I told her that I suffered from stomach problems, and that it would be helpful if I received a teaspoon of oil before meals. My cellmates waited for her reaction, holding their breath. She suddenly replied, in a surprisingly human tone of voice, “Bring me a cup tomorrow morning, and I will get you some of the oil that sites on top of the cooked cereal.”

The next morning, she knocked on the door and asked, impatiently, “Where is the cup?” I gave her my empty cup and received in return a full cop of oil. My cellmates were shocked. “Now we need a menorah.” We thought about how to accomplish that next feat. One of the gentiles said, “We will make it from bread.” And so we did.

On the first day of Chanuka in that Gorky prison, a miracle seemed to happen. The wardens usually made their rounds and peeked in the peepholes of our doors every twenty minutes. But that day, half an hour before the time to light the menorah, they suddenly disappeared. Someone stood in front of the peephole, watching, just in case.

I gave my Russian friends the transliterated text of “Al Hanisim,” the prayer extolling the Chanuka miracles, sung after the lighting of the menorah. I lit the match, ignited the oil in the brad menorah and said the three blessings. My cellmates answered, “Amen” and sang “Al Hanisim” with me. While the oil burned, for thirty minutes, no one came to check our cell. It had been an hour altogether, during which time they should have come by to check three times.

For eight days I lit the menorah, said the blessings and we sang. For eight days, no warden came to check our cell during that hour.

On the last day, after I lit, my cellmates said, “There is oil left. Let’s go on.” I said, “No. Next year I’ll continue – as a free man, and you, as free men, will tell your friends the story.”

The next morning the elderly warden came by. I asked her something, thinking we were friends now, and she barked at me nastily. Her good humor had lasted only for the period of Chanuka. “For eight days she was different so we could perform the mitzvah,” I told my cellmates. “That is the way God worked.”

That was my first and last Chanuka in that particular prison. Even in a place where horrifying events occur, God tried to show us that there is light, light with great hope.

My three-year sentence was commuted to two years. I was released from the hard labor camp on Purim, 1988, and arrived in Israel two days before Passover, another festival of freedom.

*

Toby Klein Greenwald is an award-winning journalist, theater director and editor-in-chief of WholeFamily.com. Before Ari and Mila Volvovsky make aliya, Klein Greenwald directed a play on Ari’s kangaroo trial, in Efrat, the town that adopted the Volvovsky family while they were still in the USSR, and where they live until today.