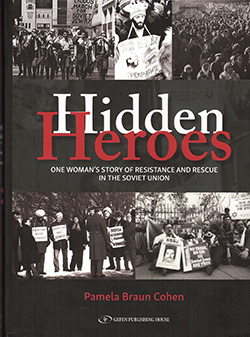

Hidden Heroes: One Woman’s Story of Resistance and Rescue in the Soviet Union by Pamela Braun Cohen; Gefen Publishing House © 2021; ISBN 9789657-023365; 393 pages including appendices and an extensive index.

SAN DIEGO – Future historians will consider this book a great find as it details over 20 years of protest, militancy, press releases, controversy, speeches, victories, and defeats in the campaign by secular American Jews to win the right of refuseniks in the Soviet Union to emigrate.

SAN DIEGO – Future historians will consider this book a great find as it details over 20 years of protest, militancy, press releases, controversy, speeches, victories, and defeats in the campaign by secular American Jews to win the right of refuseniks in the Soviet Union to emigrate.

Numerous frustrations hindered author Pamela Braun Cohen during the years that she led first the Chicago Action for Soviet Jewry (CASJ) and later the nationwide Union of Councils for Soviet Jews (UCSJ), but there were also times of pure elation as she befriended and worked closely with Refuseniks and American and international political leaders in her efforts to win freedom for Soviet Jews.

Measures of her success can be seen in the blurbs in praise of this book from such recognizable figures as Natan Sharansky, Alan Dershowitz, Yosef Mendelevich, Dennis Prager, Elliott Abrams, Jonathan Sarna, Stuart Eizenstat, and Josef I. Abramowitz. There are also photos of the author with Menachem Begin in 1981, George Shultz in 1986, Natan Sharansky in 1986, Vladimir Slepak in 1987, Harold Washington in 1987, Ronald Reagan in 1987, Rabbi Avi Weiss in 1988, George H. W. Bush in 1990; Dennis DeConcini in 1991; Vytauta Lansbergis in 1991; Evgeny Yevtushenko in 1992 and Yuli Edelstein in 2010.

In fighting for the freedom of Soviet Jews, Cohen relied heavily on the Jackson-Vanik Amendment which denied normal trade relations, programs of credits, credit guarantees, and commercial agreements to the Soviet Union until such time as that nation demonstrated an ongoing commitment to human rights. As long as Jews were being refused permission to emigrate, and, worse, imprisoned on trumped up charges for making known their desire to leave, the Soviet Union was clearly in breach of Jackson-Vanik’s conditions for improved economic relationships.

Israel, meanwhile, pursued its policy of wanting every Jew in the Diaspora to resettle in Israel, a policy that clashed with UCSJ’s demand for free emigration from the Soviet Union. If it were agreed that all Soviet Jews who wanted to emigrate would be sent to Israel, regardless of their desire to live in the United States or somewhere else, then the matter of Jewish emigration from the Soviet Union would become a bilateral issue between Israel and the Soviet Union. This, in Cohen’s view, was very short-sighted because if the U.S. were left out of the equation, there would be no reason for it to try via the Jackson-Vanik Amendment to persuade the Soviet Union to liberalize its emigration policies. While the U.S. was strong and important enough to the Soviet Union to exercise considerable leverage, Cohen believed that tiny Israel would be unable to greatly influence Soviet policy. She feared that in turn would work to the detriment of Jews seeking to leave the Soviet Union.

That position brought her into philosophical conflict not only with Israel, but also with what she called “The Jewish Establishment,” typified by the Conference of Presidents of Major American Jewish Organizations then led by Morris Abram.

So, while major Jewish figures all voiced support for the rights of Soviet Jews, behind the scenes, there were major differences in how that support should be translated in practical terms.

As Cohen attracted more members of Congress to the Soviet Jewish cause, as well as members of successive presidential administrations, she became recognized as an important voice in the struggle. She was frequently a presence at international conferences on human rights, some of them even in the Soviet Union, where she was closely monitored, yet tolerated because of the obvious political clout her organization had developed back home in the U.S.A.

A secular Jew, Cohen went through a slow process of transformation during the struggle for Soviet Jewry. Seeing how Soviet Jews would risk prison, beatings, even death to exercise their Jewish identities –– she wondered why her secular life had been so devoid of the religion and the heritage. Surely, she thought, Judaism meant more than activism, even if that activism was in pursuit of the ideal of tikkun olam, helping to repair the world.

As the Soviet Union transformed into 15 independent states and some million Jews emigrated to Israel alone, Cohen was drawn increasingly to Jewish religious studies – a quest that led and her husband Leonard to establish a second home in Jerusalem.

In so many ways, the campaign for Soviet Jews was transformative.

*

Donald H. Harrison is editor of San Diego Jewish World. He may be contacted via donald.harrison@sdjewishworld.com