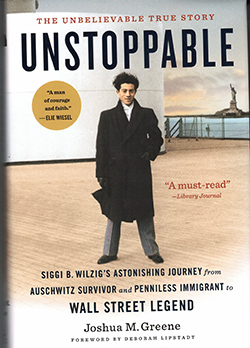

Unstoppable: Siggi B. Wilzig’s Astonishing Journey from Auschwitz Survivor and Penniless Immigrant to Wall Street Legend by Joshua M. Greene (foreword by Deborah Lipstadt); San Rafael, California: Insight Editions © 2021; ISBN 9781647-222154; 315 pages including appendices, acknowledgments, bibliography and notes; $29.99

SAN DIEGO – Before I tell you how Siggi Wilzig became a “Wall Street legend,” let me tell you about the kind of jobs he had after immigrating to the United States as a survivor of Auschwitz.

SAN DIEGO – Before I tell you how Siggi Wilzig became a “Wall Street legend,” let me tell you about the kind of jobs he had after immigrating to the United States as a survivor of Auschwitz.

His first job was shoveling snow for $2 a day. On the second day, he found two neighborhood kids to do the job for him for 50 cents a day each. He pocketed the extra dollar. Next, he worked in a sweat shop affixing linings to the inside of school bags. He made $28.50 a week at that job, until he offered to also clean the toilets. That brought his paycheck to $30. Next, he went to a bowtie shop for $36 per week, with a commission on every dozen bowties he could make. From there he went to the Brooklyn Master Craft Necktie Company to work as a salesman.

With Larry Nartel, who also had survived the concentration camps, he went on road trips, selling the ties door to door in small towns. Depending on their quality, the ties cost $1, $1.50, and $2. When that proved less than lucrative, Wilzig went to work for National Pictures, a company that sold furniture, housewares, and other goods to people from a catalog.

After marrying Naomi Sisselman against her wealthy parents’ wishes, he became a salesman of leather-bound loose-leaf binders, which he sold on road trips from one college to another. So that he wouldn’t be out of town so often, he switched jobs and became a furniture salesman for Nieswand and Son in Hillside, New Jersey. In a matter of weeks, he tripled the company’s business and was promoted to general manager. His father-in-law, Jerome Sisselman, finally recognized Wilzig’s talents and put him in charge of a gravestone business from which Sisselman, as an owner of a mortuary, was required by the government to divest. Once again, Wilzig boosted sales remarkably.

In his spare time, Wilzig studied the stock market and carefully invested. One company that attracted him was the Wilshire Oil Company. At a social event, he met 78-year-old entrepreneur Sol Diamond, who was a major shareholder in mining companies and other businesses, After some small talk, they discovered that they both owned shares in Wilshire Oil Company. Impressed by Wilzig’s knowledge and drive, Diamond invited Wilzig to join him in a takeover of the company, which they both considered to be prospect-rich and leadership-poor.

Thus began the second chapter of Wilzig’s climb to financial success. Author Greene details how Wilzig eventually took over the Wilshire Oil Company in 1965. After Wilshire purchased numerous shares of the Trust Company of New Jersey, Wilzig was able in 1971 to become chairman and CEO of that company as well. One company helped the other until 1982 when the Federal Reserve forced Wilshire to divest its banking interests. Just as Sisselman had appointed him to run the gravestone business, now Wilzig appointed his own 25-year-old daughter Sherry to run Wilshire Oil Company. While not officially in control, Wilzig was able to persuade his daughter to run the business as he would.

As a multimillionaire, Wilzig had two major passions: Holocaust remembrance and support for Israel. In 1975, Israel awarded him the Prime Minister’s Medal in recognition of his contributions. In 1979, at the suggestion of his friend Elie Wiesel, he was sworn in as a member of the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum Council. The once penniless immigrant was invited to the White House where he and Naomi dined with Jimmy and Rosalynn Carter. In 1982, during Ronald Reagan’s presidency, Wilzig participated in a Holocaust Remembrance candle lighting ceremony at the White House.

Later, when Reagan made the controversial decision to visit the cemetery at Bitburg, Germany, where Nazi SS men were buried among other German war casualties, Wilzig denounced the decision on Barry Farber’s national radio show.

In relating Wilzig’s remarkable success story, Greene recited many anecdotes about Wilzig’s voluble speech and mercurial personality. Although Wilzig became a wealthy and influential man, he often said that psychologically he still was at Auschwitz, doing whatever he could to protect himself.

Wilzig died in 2003, his extensive testimony about his Holocaust experiences the subject of longer-than-usual videotaping sessions arranged by Steven Spielberg himself.

*

Donald H. Harrison is editor emeritus of San Diego Jewish World. He may be contacted via donald.harrison@sdjewishworld.com

Most profound reflection of how invidious post trauma can be: “ Wilzig became a wealthy and influential man, he often said that psychologically he still was at Auschwitz, doing whatever he could to protect himself.”. Great review!

Another inspiring story of a Holocaust survivor. Thanks for this review.