Schlepping and Schmoozing Along the Interstate 5, Chapter 22, Exit 15B (B Street); San Diego City College

From left branch of B Street exit turn left from bottom of offramp to B Street and follow to Park Avenue. Turn right to front of college at 1313 Park Boulevard.

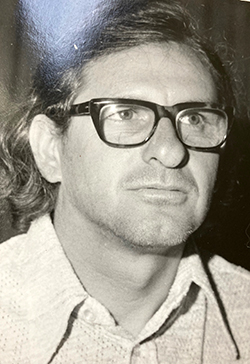

A large crowd gathered on December 1, 1995, to rename the Quad at San Diego City College as Schwartz Square. The gathering was in honor of history professor and American Federation of Teachers #1931 President Larry Schwartz. He had died at age 62 of a brain tumor ten months prior to the ceremony.

A large crowd gathered on December 1, 1995, to rename the Quad at San Diego City College as Schwartz Square. The gathering was in honor of history professor and American Federation of Teachers #1931 President Larry Schwartz. He had died at age 62 of a brain tumor ten months prior to the ceremony.

The dedication plaque there reads: “In memory of Larry Schwartz. He inspired students, challenged colleagues, and shared the passion and action of his time.”

Much was implied, rather than said, in the plaque’s words. Some of those colleagues whom he “challenged” disliked him intensely, while others gravitated toward his leadership. Some of the students he “inspired” espoused causes that at times made others at the college, and society at large, uncomfortable. The “passion and action of his time” included trade unionism, the civil rights movement; socialism, and anti-Vietnam War activism.

To learn more about Larry Schwartz, I interviewed his widow, Rosalie, as well as Michael Kuttnauer and Jim Mahler, the two subsequent presidents of AFT 1931, and his fellow union members Jonathan McLeod and Charles Zappia.

Rosalie Schwartz, Larry’s widow had a career as a professor of Latin American Studies at San Diego State University. She related that there had been considerable opposition to renaming the Quad, which then was the campus “Free Speech area,” after her husband. She stated, “There was a group that was against it on principle because they said, ‘Where do you stop? If we’re going to name something for someone on the faculty, how many faculty members are you going to memorialize?’ It wasn’t a unanimous decision.”

(Photo courtesy of Rosalie Schwartz)

About her husband, Rosalie Schwartz said, “He was willing to be the faculty sponsor for various groups …that were, I think, more liberal than the administration would have liked.” Among the student groups he sponsored or encouraged were the Socialist Workers Party, Black Panthers, Students for a Democratic Society, Congress of Racial Equality, and the list went on. Larry’s own political affiliation was with the Democratic party; he was a delegate pledged to George McGovern at the 1972 Democratic National Convention.

Rosalie recalled that she was 15 and a member of B’nai B’rith Girls when she met Larry, who was nearly 19 and training during the Korean War at Scott Field near Belleville in southern Illinois and close to St. Louis, Missouri, where she lived. The Young Men’s-Young Women’s Hebrew Association (YM-YWHA) and the USO hosted activities for the enlisted men, including lox and bagel brunches on Sundays.

Rosalie reminisced, “My parents (the Vinocors) were not thrilled; this very brash young man from Brooklyn. I had a younger brother (in addition to an older sister) who was almost ten years younger than me and somehow or another Larry felt he knew how to raise a young kid better than my parents. My parents didn’t appreciate that. Understandably, they felt that I was too young to be going out with this Air Force guy at 15. In St. Louis, in the Jewish community, they knew everybody, so anyone I went out with, they knew the family history. Not with Larry, because he was not from St. Louis.”

The Vinocurs decided to move to Los Angeles, figuring that one side benefit would be that Larry would be left behind. But Larry arranged to be transferred to Mather Air Force Base in Sacramento, and when he had enough days off, he drove down to Los Angeles and surprised the family at their front door. Always known for his persistence, he persuaded Rosalie to marry him in New York in 1954. Rosalie’s parents and siblings traveled for the occasion to New York City where she worked as a secretary. In 1956, he was graduated and earned a teaching credential from Queens College. Eventually, Rosalie persuaded Larry, “kicking and screaming” to return to Los Angeles, where he taught history at Thomas Starr King Junior High School and also earned a master’s degree in American Studies from Cal State Los Angeles. He started a doctoral program at the University of Southern California but was diverted by an offer to become a supervisor of student teachers studying at Cal State Long Beach.

He successfully applied for a 1965 Fulbright Fellowship to teach methodology to future English instructors at Sardar Patel University in the Indian state of Gujarat, which, incidentally, was the home of India’s future Prime Minister Narendra Modi. Rosalie’s parents demanded, ‘What do you mean that you are taking our grandchildren to India?!’ but that’s exactly what Larry and Rosalie proceeded to do. The couple had two young daughters, Phyllis, then 10, and Thelma, then 6. As the Fellowship year wound down, “Larry applied to various community colleges, and was brought for an interview and hired at City College here in San Diego. That is how we got to San Diego.”

Michael Kuttnauer was hired in 1966 to teach philosophy at San Diego Mesa College, one of three campuses in the San Diego Community College District – the others being City College and Miramar College (founded in 1969). “I was beginning to become active even though I was a very junior faculty member at Mesa” Kuttnauer said. “He (Larry Schwartz) was anti-Vietnam War, he was pro-Civil Rights, and I was the same and that was what linked us.” The relationship developed into a close personal friendship.

“One of the things that I noticed about Larry was how interested he was in children,” Kuttnauer continued. “He loved kids. He loved your kids; he loved my kid, David, my son. He was very good around children in the way that some people are, but many people are not as adults. That always tells me something about a human being. Do they like kids? Do they like to be around kids? Larry loved them; he loved the word play, verbal humor, the irony. He could do that.”

He also loved baseball, Kuttnauer recalled. “We used to go to Qualcomm and I used to make fun of him as he dipped his nose into the mustard on the hot dog, leaning down to eat it. There was a big clump of mustard on it. I would walk over with a napkin and just help him out a little bit. ‘Lar—you did it again!’ He rooted for the Padres. I was still a Dodgers fan at that point in my life, which he should have been because he hailed from the Brooklyn area, but he abandoned them.”

No, Rosalie corrected him, “He was a Yankees fan.”

Schwartz and Kuttnauer, respectively at City College and Mesa College, began to work together to build the union. “At that time, there was no collective bargaining in California for public employees, so he and I, and many others tried to organize a faculty union,” Kuttnauer said. “Collective bargaining came in 1977” after the Legislature passed a bill by State Sen. Al Rodda, D-Sacramento, authorizing public employees to form unions. Initially, the community college faculty decided to be represented by the California Teachers Association, which also represented teachers in the K-12 system. “Management was a big part of the CTA,” Kuttnauer said. “You could go be a member of CTA and an administrator in those days.” Also, Kuttnauer said, “they tended to have more ‘conservative members who joined them. We took the more radical, liberal and progressive members in the AFT guild.” As one of Kuttnauer’s colleagues described it: “You recognized the conservatives at Mesa driving the cars that have chrome bumpers that are immaculately polished, and the liberals were all the others.”

The California Teachers Association pointedly described itself as an “association,” similar to the California Medical Association, conveying the idea that faculty members were professionals, as opposed to labor union members who were “workers,” said Kuttnauer.

On three different occasions, the American Federation of Teachers was defeated in its efforts to decertify the California Teachers Association as the bargaining agent for the faculty of the San Diego community colleges. However, it was successful on its fourth try in 1987.

In a 2006 history of AFT 1931, Democracy in Education: Education for Democracy, Kuttnauer remembered that “a lot of people were really opposed to AFT. It’s hard to separate whether some of these people were opposed to AFT or Larry himself. There were a lot of people who responded negatively to what a New Yorker takes as the everyday way of approaching people. And they didn’t understand him. In spite of the image of California being casual, there was an aloofness in the way people approached each other in the ‘academic setting’ that produced boundaries that Larry didn’t see. He didn’t approach people that way. So that was a problem.” Then, “he became identified with left-wing politics and the kinds of things that a lot of people were not interested in and didn’t think belonged on the campus,” Kuttnauer stated. “They were opposed to him personally and, as he became more identified with AFT, they combined the two. If the AFT and Larry were involved, some people thought they would be leading the campus into the pits of Hell. So, there was a kind of anti-leftism.”

Charles Zappia, a future dean of social/ behavioral sciences and multicultural studies who began teaching history at Mesa College in 1986, was distressed when he learned that the CTA had negotiated two separate salary schedules—a higher pay schedule for professors who had started teaching before him, and a lower pay schedule for newcomers like himself. In reference to the California Teachers Association, “I met the CTA people who were nice enough people as human beings, but their politics were miserable. I mean, they had negotiated this worthless contract, so then after six months at the most after I had been going to board [of community college trustees] meetings and complaining about this, I heard that AFT was going to finally try to organize Mesa again. I heard the name ‘Larry Schwartz’ mentioned several times and what I heard from the more conservative, older faculty of Mesa was not nice. Some of it was antisemitic, some of it was ‘Larry Schwartz is a little bit off his kilter’ and so, it sounded to me like he was a guy I very much wanted to meet.” One professor reportedly described Schwartz to his colleagues as “a real kike.” According to Zappia, “that kind of stuff was endemic in those days.”

The national office of the American Federation of Teachers recognized that Larry’s personality might be an impediment to organizing the faculty at Mesa College, so it sent out Norm Holzinger, who wore a suit and tie and had a doctoral degree in his resume. This impressed faculty members who considered themselves professionals and not workers. Larry meanwhile was instructed to confine his activities to the City College campus.

“The AFT won the election, thank God, and Larry, knowing that I had strongly opposed the two-tier salary schedule, asked me to join the bargaining team,” Zappia said. “So, I bargained along with Larry from about 1987 until he passed away. What I can say about Larry and bargaining is several things. First of all, he always kept his sense of humor – always, always. Second, he never attacked district negotiators. … Also, when it came to organizing while we were bargaining, Larry tried to organize everybody including some of the most reactionary people I wouldn’t want in my union, but Larry was very open to everybody.”

One of the chancellors of the San Diego Community College District, with whom Larry negotiated was Augie Gallego. “Whenever Augie would start coming to the room, Larry would say, ‘Oh, here comes Augie he’s so tight, his shoes squeak.’” Zappia recalled. “Larry had the kind of personality that his comments generally didn’t anger people.”

Gallego was quoted in 1995 by the San Diego Union as describing Schwartz as a “quintessential teacher who cared for his students, his community and his discipline. He was recognized statewide for his work.” After one exhausting negotiating session, “I was tired and decided to go to a movie to relax,” Gallego recalled. “I went to a theater in La Jolla, sat down and felt an arm reaching across my shoulder. There was Larry, saying, ‘Can we talk?’”

Jonathan McLeod, a history professor, said that when Larry visited Mesa College during his union presidency, “the faculty was somewhat diverse. People of international backgrounds, some African-Americans, a few Asian-Americans, some Latinos as well as a majority of European-American Anglos. Larry would often call out people, refer to them by name, where they earned their degrees, and applaud them for their knowledge and commitment to education. That made people feel good about him; they felt that he was acknowledging them. … Larry was a person who celebrated efforts of other people to make a difference in the world.”

Larry also could be difficult at times.

McLeod remembered flying to Washington D.C. with Larry, who talked the passenger at the window seat to relinquish it and take the middle seat instead. “Larry asked some sort of question that would get us talking and then Larry promptly went to sleep…. Then we were in Washington talking to various legislators and I remember going into the office of Randy ‘Duke’ Cunningham, who was an obnoxious person as well as being extremely right wing …. Larry’s opening question of Duke Cunningham was ‘Why the hell are you a Republican?’” Cunningham early in his career had been a Democrat. “Larry was trying to walk him around to a more reasonable position. It didn’t work but that was typical of Larry.”

Jim Mahler, who became the AFT president in 1996 and was still going strong in that office at the time of our interview in 2021, confided that before he met Larry, “I was pretty much an introvert … Being around Larry and seeing how he dealt with people, met with people, and interacted with people really got me out of my shell. We would walk into the deli, and he would befriend the person making the sandwich and before they are done, they were best friends.”

Mahler, a professor of engineering, math and physics, had started as an adjunct in 1987, the year the AFT won the right to become the collective bargaining agent for the faculty at the community colleges. “The next fall, I run into Larry in the mail room – this was before computers and the internet, when the only communication was stuffing mailboxes, which Larry did, and I did a lot. I said, ‘Hey Larry, I would like to get active in the union. What can I do to help out?’ He said, ‘Come to my house Saturday; you are on the Exec Board.”

Sometime later, Mahler asked Larry and Michael why given his inexperience, they had decided to put him on the Executive Board. And Mike (Kuttnauer) said, “No one else would work with us.” Zappia smiled and offered, “I remember Larry said to me ‘we ought to get this kid at City College. He is a hard charger.”

“That was my indoctrination in the union and then I remember we wanted to have some event at City. I had the brilliant idea: ‘Larry let’s do this thing, this event.’ He said, ‘Okay, set it up.” And I thought, ‘Shit! I don’t know how to set it up!’ and that helped me grow as well because I had to talk to people in food service, and get the room …Just his way of doing things that helped me develop as a leader.”

At meetings of the Community Colleges Board of Trustees, Mahler recalled, the board first met in executive session, then in public session, and only after that did it have a time for public comments. {That since has been changed so the public can go first.} Larry would always sit in the front row… waiting, dying, you know, and I remember sometime someone was talking and Larry was sitting in the chair with arms like this” – Mahler imitated a man sprawling – “and someone is going yak, yak, and Larry just goes, “Ohhh Fucccck!’ really loud. It was hilarious. I don’t think he consciously thought it; it just came out.”

The first big contract that Larry settled was with then Chancellor Garland Peed. “They had lunch and he come back with a napkin and on it is 9 percent and 8 percent” – the percentage raises faculty would receive in year one and year two. “He had lunch and it is on a napkin.”

The decision to memorialize Larry with the name Schwartz Square came at a time when City College still considered the Quad to be the “free speech area.” Courts since have decided that students should have free speech anywhere on college campuses. Schwartz was one of the people on campus who not only supported the idea of free speech, but often exercised it. “Maybe that was where it all started, where he got his start speaking,” Mahler said.

“People at City College said that Larry Schwartz would stand up on the third floor of the building and engage people in discussion on a variety of controversial topics and people would join in, so Larry’s presence was felt on the square.”

“People at City College said that Larry Schwartz would stand up on the third floor of the building and engage people in discussion on a variety of controversial topics and people would join in, so Larry’s presence was felt on the square.”

Since Schwartz’s day AFT #1931 has also become the bargaining agent for faculty and classified employees at the two campuses of the Grossmont-Cuyamaca Community College District in El Cajon. The union recognizes Larry’s contributions internally by offering $500 scholarships to any student who is part of a union family who writes a persuasive essay on why unions are important.

Mahler estimated that over the years, the union had awarded at least 250 such scholarships in Larry’s name.

*

Next Sunday, June 5, 2022: Exit 15B (B Street): San Diego Symphony

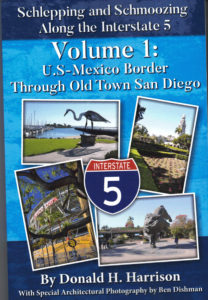

This story is copyrighted (c) 2022 by Donald H. Harrison, editor emeritus of San Diego Jewish World. It is an updated serialization of his book Schlepping and Schmoozing Along Interstate 5, Volume 1, available on Amazon. Harrison may be contacted via donald.harrison@sdjewishworld.com