By Dorothea Shefer-Vanson

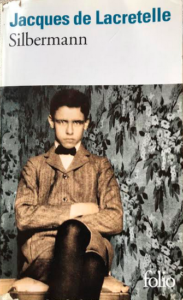

MEVASSERET ZION, Israel —The novel Silbermann by Jacques de Lacretelle, which I read in French, was first published in 1922 It describes the life of a French schoolboy and his relations with a Jewish classmate. The general atmosphere in the school is one of rigid discipline and, as is often the case with teenagers, the pupils tend to form friendships and cliques which exclude anyone who is different.

The boys are divided by religion, with some of the pupils residing in a Catholic institution, while others, including the narrator, are generally Protestant and live with their parents in a suburb of Paris.

The book begins as the youngsters return to school after the long summer vacation. The narrator’s friend, Philippe Robin, returns from the countryside where he has been instructed in the arts of hunting, fishing and shooting by his uncle, and has absorbed his relative’s anti-Semitic sentiments, complaining that the environment was tainted by “too many Jews.”

The arrival in their class of a Jewish pupil passes without undue attention until one of the teachers calls upon the Jewish pupil, Silbermann by name, to recite a passage from one of the books they have been required to read. The narrator is struck by the Jewish pupil’s ability to infuse meaning into the phrases, bringing him to a fresh understanding of the text.

The arrival in their class of a Jewish pupil passes without undue attention until one of the teachers calls upon the Jewish pupil, Silbermann by name, to recite a passage from one of the books they have been required to read. The narrator is struck by the Jewish pupil’s ability to infuse meaning into the phrases, bringing him to a fresh understanding of the text.

A chance encounter with Silbermann when both are out walking in the woods near Paris brings the narrator to the realization that his new classmate, who is evidently endowed with superior intellectual abilities to the other boys, is subject to discrimination and isolation by the rest of the class. Entranced by the prospect of benefiting from the knowledge and intelligence of Silbermann, the narrator takes upon himself the mission of befriending him and redeeming him from his isolation.

The relations between the two boys grow stronger, with Silbermann imparting his wisdom and insights to the narrator, and the narrator happy at finding the intellectual stimulation that he has been unable to obtain from the other boys. As their friendship grows, the other boys in the class become increasingly aggressive and violent towards Silbermann, so that during the recess he is subjected to verbal and even physical taunts and attacks. While the narrator is unable to protect his friend from the attacks, he remains by his side and is himself eventually isolated and shunned by his schoolmates.

The visit by the narrator to Silbermann’s home reveals a luxurious apartment around which contains objets d’art (Silbermann’s father is an antique dealer), and he suddenly sees that his own home is not in the best of taste. His own father is a lawyer, and by chance it falls to him to adjudicate in a case where Silbermann’s father is accused of fraud. At his friend’s request, the narrator seeks to intercede on Silbermann senior’s behalf with his father, whereupon he is subjected to a lecture about the sanctity of the law, the pursuit of justice, and the absolute refusal of his father to take any personal relations into consideration.

The narrator’s parents advise their son to abstain from any further relations with Silbermann, and it is at their instigation that Silbermann’s father is asked to remove his son from the school. This leaves Silbermann with no option but to leave France and join his uncle in the U.S. where, instead of becoming a man of letters, as he had hoped, he will become a merchant in the jewelry trade.

Before Silbermann leaves France he and the narrator have one final meeting in the woods where they first met. Silbermann embarks on a lengthy tirade, telling his friend that Jews will always rise to the top wherever they are, that they are a superior race, that “the chosen people” is not just an empty phrase but the true nature of Jews everywhere. Enumerating the wealthy Jewish families in Paris and their lavish homes, he derides the intellectual inferiority of the nations in which Jews find themselves, and the benefit those nations derive from having Jews in their midst. This speech, which combines brilliance with arrogance, leaves a lasting impression on the narrator (and on this reader).

Bearing in mind that this book was written in 1922, long before the Holocaust and all the horrors it conveyed, there us something almost visionary in the account of the behaviour of the boys in the class, in many cases even aided and abetted by their teachers, as well as in the account of Silbermann’s arrogance and sense of intellectural superiority.

At the end of the book the narrator finds that in order to curry favour with an important politician, his father has exonerated Silbermann’s father, and this realization causes his ultimate breach with his parents.

I found this well-written book both gripping, entertaining, and enlightening, and would recommend it as a prescient account of life in pre-war France (and Europe) for anyone who is prepared to make the effort to read it in French.