Chapter 26, Exit 17A (Hawthorn Street): County Administration Building

From exit, follow street as it curves to the left and continues to Pacific Highway. Turn left. The County Administration Building is at 1600 Pacific Highway.

From exit, follow street as it curves to the left and continues to Pacific Highway. Turn left. The County Administration Building is at 1600 Pacific Highway.

If he were so inclined, Greg Smith could have a lot to brag about. Over a period of 25 years, he won seven elections to serve as the San Diego County Assessor as well as the county’s recorder and clerk. He headed a staff of between 400 and 500 county workers in the combined operations of assessor-recorder-clerk.

Yet, characteristically, when he relates anecdotes about the two and a half decades he spent as an elected official before taking a job in private industry, Smith prefers to tell self-deprecatory stories. He was serving as chief deputy assessor to E.C. Williams in 1983, when Williams decided to call it quits. On a 3-2 vote, the Board of Supervisors decided to allow Smith to fill the vacant position until the 1984 election when someone could be chosen to fill the balance of Williams’ four-year term.

Smith was in his early 30’s at the time and had been serving as chief deputy assessor for only a year. Remembering when he sat in the Board of Supervisors’ chambers awaiting their vote, he recalled thinking, “Oh my God, this is the most important day, the most important time of my life and nothing could be more important.”

Then, he became aware of a click-click sound next to him in the aisle. When he looked over, he saw a man in a wheelchair who was drawing on his oxygen supply, which click-clicked every time he took a labored breath. Smith said at that point he remonstrated with himself: “Greg, you are such a silly SOB. Here you are worried about this appointment and this poor guy is fighting for every breath to live!’

It was a lesson he said he never forgot.

Another indelible lesson came a few years earlier while he was serving as the ombudsman for the City of Chula Vista – an office designed to hear citizen complaints and to initiate inquiries to the relevant officials in city government to get answers.

“If they were sick of the bureaucracy, they would call me,” Smith told me. “Usually, it was things like tree trimming or a problem of not getting their trash picked up, or potholes, whatever the case might be.”

“The lesson I learned was a very important lesson. In the City of Chula Vista, they had council meetings every Tuesday night at 7 p.m. Anybody could come up on any subject that was not on the agenda and talk to the City Council. I remember I was in the audience and this one guy comes up and says, ‘Hey, I’ve been trying to get ahold of this guy Greg Smith’ – and the councilmen and the manager are looking at me like they were going to kill me – ‘and I have a flooding problem at 4th and J Streets.’ I had referred it to Public Works, but I had not gotten back to him yet. He said, ‘Nothing has happened. I have not gotten any response.’ So, the City Manager says, ‘Mr. Smith is in the audience and Mr. Smith will meet with you right after the meeting and will take care of it.’ I rushed after this guy and took care of it, and from that I learned that you should always take care of business. … I made sure that they (staff members) got back to me. Every Monday, or Tuesday, I would go to the people who made a complaint and say, ‘Have you gotten a response from staff yet?’ That was something I developed early on and checked to make sure that the staff got back to the people and got that matter resolved. I never wanted to be embarrassed again at the council.”

The lesson influenced his management style while serving as the county assessor. “I developed a tickler system which was an accordion file numbered 1 to 31,” he said. He’d give the dozen people who directly reported to him a written assignment and “I’d give them a copy and I would take a copy myself, and say, ‘Okay, I want this back in two weeks.’ On February 15th, say, I’d look in the file on my desk and I would pick up the phone. “Joe, what happened on that assignment? What is going on?’ That basically was how I assured accountability. I know that people have these things on computer now, but back in the day they didn’t have that, so I had a manual tickler system. There were requests from the Board of Supervisors, citizens, the State Board of Equalization, a myriad of different things that had to be responded to in a timely fashion. So, I trusted, but always verified—the Ronald Reagan approach.”

Another management technique that Smith favored was management by walking around. “I would go into the different offices. I didn’t just pick up the phone; I walked around. I talked to the staff on a regular basis. I went down to the auditor, met with the CAO, Tax Collector, Supervisors if they had questions. The staff always wanted to see the boss there; they wanted to know that the boss was working and that the boss cares.”

The Assessor’s office evaluates for tax purposes the private properties within the county. The recorder keeps records of land and property transactions. The clerk maintains the record of vital statistics –births, deaths, and marriages. It issues marriage licenses, and, in what Smith said was the favorite part of his job, conducts weddings for between 40 percent and 50 percent of the couples who marry in the County.

“I did a lot of ceremonies,” Smith said. “I had the couple looking at the audience and I stood off to the side. They didn’t want to see my ugly punim; they wanted to see the bride and groom.” Smith also officiated at gay weddings, which California legalized during his time in office.

Smith also deputized friends or relatives of the couple to conduct the wedding ceremony if that was what the bridal couple wanted. Standard vows were written out for the deputized officiant, and Smith would instruct what portions were legally required and which could be left out or substituted. “One of the things I always encouraged them to do was to prepare some personal vows. I always stressed write it down. Don’t memorize it. I had them put it on an index card and then have them say it. Invariably one would get nervous and forget their lines, so I would pull out the card and give it to them and everything worked out of time.”

To make the weddings more memorable, “we would sell them a Polaroid picture of them signing the license. We would sell them a commemorative pen that they signed their marriage license with, and the ceremony was filmed, and we would sell them a video of the ceremony. … We had weddings in the ‘Arbor of Love’ outside. We had weddings on the web for military families for whom we had a special room with video cameras so the parents could see their son or daughter getting married live.”

To make weddings and other services of his several offices more accessible, “we had branches in Chula Vista, El Cajon [since relocated to Santee], Kearny Mesa, North County plus the County Building … I wanted people to be served in their communities, not to have to drive downtown, and I didn’t want long lines. If we had lines at our offices, I’d tell staff ‘Pull our people from the back and get them to the counter. We do not want people waiting in line.’”

He said he also made it a practice to personally interact with the public. “I took phone calls all the time from angry property owners” who were upset by the size of their property tax assessments. “I would listen to them and say, ‘I can’t promise you anything; I will look into it [and] get back to you.’ … I took those calls directly, referred them to staff, and we got back to them, maybe not with good news – we couldn’t lessen the assessment or something like that – but at least they got an answer. .. That was a top priority of mine: public service.”

The former assessor noted that people in La Jolla sometimes would ask his office to remove offensive provisions from their property deeds, such as the prohibition in former times against Jews, African-Americans, and Asian-Americans buying property in La Jolla. As much as he sympathized, “I said we can’t do that. The restriction is null and void; the Rumford Fair Housing Act wiped all that out. We can put a stamp on it, ‘No longer applicable’ but we cannot unring the bell. We cannot remove that part of history, that part of the legal document.”

He said the way real estate agents circumvented the law was by never posting ‘For Sale’ signs on the properties in La Jolla. “Everything was a pocket listing. So, you’d go to a realtor. ‘Mrs. Smith, there’s a beautiful house down the street. Mrs. Goldberg, I just don’t have anything for you here. But maybe Pacific Beach is a good area.’ That’s how they did it. No ‘For Sale’ signs.”

Smith said his service-to-others philosophy was greatly influenced by his mother, Isabel Dorothy “Janet” (Weiner) Smith, who was Jewish and who raised him Jewish with the support of his father, Robert Smith, who was not Jewish. His mother always stressed to him to “be a good person, a mensch. Always help other people.’ This teaching was augmented by his bar mitzvah training at Rodef Shalom in San Rafael, “treating others like you wanted to be treated yourself, the Golden Rule. I have never intentionally tried to hurt anyone.” Smith and his wife Arlette were married at Congregation Beth Israel in San Diego and their two children, Julie and Harrison, had naming ceremonies there.

After 25 years in office, Smith decided it was time for a change. “I was approached by Conrad Prebys, the philanthropist who I had known for many years, and he wanted me to oversee his apartment complexes. I had lots of energy, I was close to being maxed out in my retirement, and I sought new challenges. So, I went with Conrad and that was a great experience. Conrad said to me, ‘Remember, Greg, property management is not rocket science.’ It was just a lot of hard work. I managed his portfolio, I think about 7,200 units at that time, and then when poor Conrad passed away, we had to start selling some of the portfolio, which wasn’t exactly what I wanted so then I went to work for Pacifica Companies where I am now. I am overseeing a little over 12,000 apartment units from Florida to San Diego to Seattle. I enjoy it.”

At the time of our interview in December 2021, Smith was 71 years old. “I have a lot of energy and good health, no hobbies, and the wife doesn’t want me around that much, so it is a perfect situation. I enjoy working; I’ve always enjoyed a challenge, and I have great bosses at Pacifica as well.”

*

From its very inception, the San Diego County government has drawn on the talents of Jewish members of the community. Louis Rose, a Jewish immigrant from Neuhaus-an-der-Oste, Germany, served in 1853 on the very first Board of Supervisors following its creation by the State of California. His inclusion among the Supervisors was automatic because he was serving at the time on the City of San Diego Board of Trustees. Today city and county government are independent of each other.

Some other pioneer Jews followed in Rose’s footsteps, among them Joseph S. Mannasse and Marcus Schiller. Among the earliest responsibilities of the Supervisors was laying out a road system to connect the cities and communities of San Diego County. These often followed the trails that been used for many centuries by the indigenous peoples of San Diego, including the Tipai, Ipai and Kamia groups of the Kumeyaay people. Some of these routes are incorporated in the Interstate 5 freeway of today, as well as the Interstate 8 and Interstate 15 freeways.

Between 2002 and 2008, three of the four independently elected countywide officials were Jewish – Smith (1983-2008); Sheriff Bill Kolender (1994-2009); and District Attorney Bonnie Dumanis (2002-2018). Had a Jew also been elected as the County Tax Collector, all four of the separately elected countywide offices would have been occupied simultaneously by a member of the Jewish community.

There also have been two Jewish members of the county Board of Supervisors. After serving there for eight years, Susan Golding went on to be elected in 1992 as mayor of the City of San Diego, in which position she served another two terms. The other, Terra Lawson-Remer, was elected to the Board in 2020 on an environmentalist platform. She has also been an opponent of so-called “ghost guns” that can be assembled from a kit without registration numbers, and she supported an ordinance requiring the county government’s new hires to be vaccinated against COVID-19.

While a member of the Board of Supervisors, Golding was married to Richard T. Silberman, who had been a co-founder of the Jack-in-the-Box fast food chain and also had served as a top executive under Gov. Jerry Brown. As the marriage was between Golding, a Republican, and Silberman, a Democrat, the marriage was occasionally described as an unusual “political alloyance.”

After returning to private life, Silberman was convicted in 1990 on a federal charge of money laundering and sentenced to 46 months in prison. The couple divorced and voters did not hold Silberman’s misdeeds against Golding. Although she came in second in the primary election, she rallied to defeat economist Peter Navarro in the general election by a margin of 222,603 to 205,448. Navarro surfaced in public life again during the presidential administration of Donald Trump, serving as his controversial and often outspoken White House director of Trade and Manufacturing Policy.

Next Sunday, July 3, 2022: Exit 17A (Hawthorn Street): San Diego International Airport

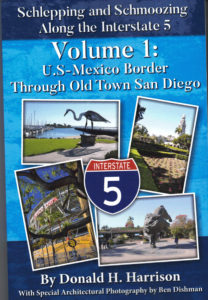

This story is copyrighted (c) 2022 by Donald H. Harrison, editor emeritus of San Diego Jewish World. It is an updated serialization of his book Schlepping and Schmoozing Along Interstate 5, Volume 1, available on Amazon. Harrison may be contacted via donald.harrison@sdjewishworld.com