HAIFA, Israel — The narrow corridor of the Physics Department of the Technion – Israel Institute of Technology in Haifa, was strewn with doors all bearing plaques with the names of professors in Hebrew. I walked down the corridor, seeing “Professor …” everywhere. When I reached the very end, I noticed a door with a small metal plaque bearing a name but without the title “Professor.”

The year before my emigration from the USSR, the Institute of Physics of the Academy of Sciences of the Ukrainian SSR where I worked, published a brochure for its 50th anniversary. I, as an “enemy of the people” and a “traitor to the motherland,” was excluded from the text of the brochure. The historical summary of the brochure opened: “For five years, beginning in 1932, Professor Lev Shtrum served as head of the Theoretical Department. (The compilers of the brochure erred: Shtrum could not have been head of the Theoretical Department for more than four years: by 1936 he was no longer alive. ̶ A. G.). […] Then, for about two years, during his stay in the Soviet Union, the Theoretical Physics Department was headed by Nathan Rosen. He worked on the theory of the atom and elementary particles.”

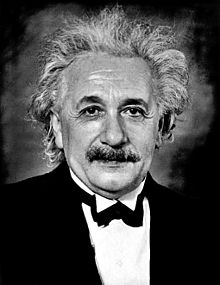

Shtrum (1890-1936), Doctor of Physical and Mathematical Sciences, also Head of the Department of Theoretical Physics at Kiev University, was condemned and shot by the KGB. He was an outstanding scientist, a talented individual, and an active citizen who was involved in the revolutionary activity popular among Jews. During one of the conferences abroad, Shtrum met Albert Einstein and received an autographed photograph from him. Shtrum was the prototype of the main character, the physicist Victor Shtrum, in Soviet writer Vasily Grossman’s novel Life and Fate. Together with 36 other defendants, scientists and researchers (the “Professors’ Affair”), he was sentenced by the Military Collegium of the USSR Supreme Court to execution. The sentence was carried out on October 22, 1936.”

In 1978, my colleague, a doctor of physics, a future member of the Academy of Sciences of Ukraine, a member of the USSR parliament in the future, a minister of science of Ukraine in the future, who tried to dissuade me from repatriating to Israel, said: “The quota system for Jews in the USSR is not discrimination, but rather the right policy to regulate relations between nationalities in a multinational country: the number of Jews admitted to universities should not exceed their percentage in the overall population.” His worldview recalls the “moderate antisemite” as defined by Jean-Paul Sartre in Reflections on the Jewish Question (1944): “A moderate antisemite is a polite person who tells you, ‘I have no hatred for the Jews. For one reason or another, I think it is necessary to limit Jewish participation in the life of the country.’” The colleague expressed this opinion after hearing my story about the persecution of my father and aunt in the “cosmopolitan” campaign (1949).

My coworker said that my decision to leave the Soviet Union would harm other Jews, explaining that even he, a “progressive man,” would not hire “potential traitors.” He saw the Jews as hostages, collectively responsible. He presented me as an enemy of the Jews, causing them harm. He said that the USSR was in dire straits, and noted that I could make a significant contribution to the country, but was choosing instead the role of deserter, hostile to the homeland that had given me so much. He accepted with ease the popular Soviet and Ukrainian narrative: during World War II, Jews were deserters and traitors. In his opinion, I was following in their footsteps and was also an anti-patriot. He accused me of the same charges leveled at my family 30 years prior during the “cosmopolitan” campaign. The circle closed. I was labeled an “enemy of the people.” He was shocked by my decision to emigrate to Israel, the world of capitalism and the country of “aggressors” and “occupiers.” I really was a “traitor” because I hated the USSR regime and did not see the Soviet Union as my country, learning Hebrew and the history of the Jewish people underground. In that country, anyone could be accused of treason against the motherland ̶ me, who did not love it, and my father, who loved it.

Neither the jubilee brochure nor the plaque on his office door explained who N. Rosen was. In fact, Rosen collaborated and co-authored with Einstein the famous article Can the quantum mechanical description of physical reality be considered complete? (A. Einstein, B. Podolsky and N. Rosen, 1935). He was a member of the Israeli Academy of Sciences and professor emeritus at the Technion. It turned out that Rosen was the founder of the very same Physics Department at the Technion in whose corridor I first encountered him.

Rosen was born in Brooklyn in 1909, two years after his parents fled from the pogroms in Russia. In 1934, Rosen became Einstein’s assistant at the Institute for Advanced Studies in Princeton and remained in that capacity until 1936. After that, Rosen worked in the Soviet Union, where Einstein had recommended in a letter to the Chairman of the Council of People’s Commissars Vyacheslav Molotov that Rosen be hired. Ukrainian researcher O.Yu. Koltachikhin (2008) outlines Rosen’s history of employment, describing Molotov’s directive to Moscow physicists to deal with Einstein’s request from a professional point of view: “From the archives of the Academician Alexander Heinrichovich Goldman (the founder and the first director of the Institute of Physics in Kiev. ̶ A. G.) it has become known that in the summer of 1936, the Institute received a letter written by order of the Presidium of the Academy of Sciences of the USSR, Doctor of Physical and Mathematical Sciences B. M. Vul, with an offer to hire Dr. N. Rosen, a young American theoretical physicist and a close associate of Professor A. Einstein, to work at the Institute. I [Goldman] immediately went to Moscow, ascertained the immediate circumstances of this proposal and, having become acquainted with Dr. Rosen, took steps to approve him for work at the Institute, which I was able to do after overcoming considerable difficulties.’”

For two years Rosen taught at the University of Kiev, the same place from which I graduated many years later. Rosen did not know Russian; his lectures were translated for students from English. For two years (1936 ̶ 1938) he worked at the same Institute of Physics, where I myself worked many years later. He told me how he, an unemployed American scientist, found work in the USSR and how he realized he had to escape when the events of 1937 ̶ 1938 began.

Why did Rosen seek work in the USSR? Daniel Kennefick, an American astrophysicist and historian of science, discusses this question in his book Traveling at the Speed of Thought: Albert Einstein and the Quest for Gravitational Waves (2007): “Born in 1909 in Brooklyn, New York, Rosen, like Infeld and many other scientists of the time, was a socialist. In accordance with his convictions, he passionately wished to live and work in the Soviet Union.” Rosen was looking for work in the Soviet Union, not only because of the economic crisis in the United States, but also for the realization of the ideas of socialism.

Upon his arrival in Kiev, Rosen was shocked to learn of the fate of his predecessor Shtrum, who had been repressed because of his acquaintance with Academician Semen Semkovsky (Bronstein), a philosopher who was Trotsky’s cousin and who had been criticized by Lenin. Shtrum was arrested on March 23, 1936, twenty days after Semkovsky’s arrest, on charges of “Trotskyist-counterrevolutionary conspiracy.” On June 2, 1936, a new article of accusation was added, the “organization of terrorist acts against the leaders of the All-Union Communist Party (of Bolsheviks),” including the murder of Sergei Kirov, one of the leading Bolsheviks, as well as cooperation with the Gestapo (as ridiculous as that accusation seems regarding a Jew).

When I told Rosen about my work at the Institute of Physics in Kiev, the first person he inquired about was Goldman. The second shock that ultimately convinced Rosen to return to the United States was the arrest in 1938 of Academician Goldman, a senior colleague of Shtrum. Goldman was a professor of basic physics and chemistry at the university. Goldman’s father, a physician, was killed during the Civil War in a Jewish pogrom in the village of Lebedin, right in his doctor’s office. Goldman experienced a pogrom of a different kind. He was accused of participating in counter-revolutionary crimes ̶ anti-state subversion and terrorist activities. He was brutally tortured during interrogations, but he categorically denied all accusations and said nothing that would contribute to fabricating a case against others, as the investigators demanded. Without a court order he was exiled to Kazakhstan for five years. During his exile he was allowed to teach in a secondary school. Goldman survived the exile, was rehabilitated in 1956 and returned to Kiev in 1959. I had time to get to know him. A year after I started working at the Institute of Physics, Goldman was killed in a car accident. At the age of 87, he was hit by a police car. Goldman and Rosen had been on friendly terms. I told Rosen what I knew from my brief acquaintance with Goldman about his life and death including details about Shtrum’s “life and fate.”

A sense of Rosen’s life in Kiev can be obtained from an article written by Ukrainian researcher O.A. Shcherbak (2012). She cites some of Rosen’s letters to Einstein, sent from Kiev: “In the first letter to A. Einstein since moving to Ukraine (February 26, 1937), Rosen wrote: ‘I do research at the Institute of Physics of the Ukrainian Academy of Sciences and teach at the University of Kiev. I am constantly busy, so much more needs to be done. But I don’t have any free time at all, unlike what I had at Princeton. But I have something more important: I feel needed and wanted (and without this feeling life is meaningless). And today I do not need to seek the support of small people in high places to earn a piece of bread. I am sincerely grateful to you for helping me to come here.’”

In Rosen’s last letter to Einstein from Kiev which is dated July 31, 1938, the tone is different: “When I last wrote to you, I had planned to visit the United States this summer. But my plans have changed. I am going back to America in a few weeks and will stay there. I am very satisfied with what I saw in the USSR, and I really like living here. The reason for this move is mainly because I’m not satisfied with my own work and not [realizing my] potential. I feel that I am not doing as much as I should. My doubt doesn’t allow me to stay here. I am going back to the States and will look for a job that is not research related. If I find one, then I will work and do research in my spare time without feeling any responsibility.” Rosen told me that he understood that the letters were being perlustrated. Rosen, who longed to live under socialism and was scared to death of its realization in the USSR, returned to the United States under the rule of capitalism.

In the U.S., Rosen worked at the University of North Carolina before repatriating to Israel, where he became a professor at the Technion in Haifa (1953). While working in the USSR, he learned to read a little Russian. I gave him a first Russian edition of Einstein’s book on the general theory of relativity from the personal library of my late stepfather, Professor of Physics Mikhail Deigen, with an inscription. One day I let Rosen read the anniversary edition of the brochure of our common Institute of Physics of the Academy of Sciences of the Ukrainian SSR, where his name was mentioned, the institute from which he had fled the inevitable repression and from which I had been thrown out as “a traitor to the homeland.” We met far away from Princeton and the Kiev of his youth and far away from the Kiev that I had forsaken. For 15 years we lived in Haifa next door to each other and often saw one another at the faculty he had created. He carefully picked up the brochure, closely read the place where he was mentioned, looked at the pictures of the Institute where he had worked for two years, and then shook my hand.

*

Alex Gordon is a native of Kiev, Ukraine, and graduate of the Kiev State University and the Technion in Haifa (Doctor of Science, 1984). He immigrated to Israel in 1979. He is a Full Professor (Emeritus) of Physics in the Faculty of Natural Sciences at the University of Haifa and at Oranim, the Academic College of Education. He is the author of eight books and about 500 articles in print and online, and has been published in 62 journals in 14 countries in Russian, Hebrew, English, and German.