By Sam Ben-Meir

BOSTON, Mass. – During his 50 years as a painter, Canadian American artist Philip Guston created a body of work that stands out as among the most significant and daring of the 20th century. His development as an artist involved several phases, and culminated with images notable for their dark, biting humor, distinct palette, unmistakable lexicon of objects, and concern with themes when taken together seem designed to heighten our uneasiness and have us question everything we thought we knew about painting. Perhaps the most important feature of these works, however, is their uncompromising interrogation of racism and white culpability, signaled by the persistent and discomfiting image of hooded Klansmen, or simply “hoods” as Guston referred to them.

The Museum of Fine Art in Boston is presently hosting “Philip Guston Now,” a much-anticipated retrospective of Guston’s work. Comprised of 73 paintings and 27 drawings, the exhibition reexamines an artist who began as a representational painter, but by the late 1950s was highly acclaimed as an abstract expressionist. Notwithstanding the adoring critics, Guston ultimately declined to settle into his role as one of the country’s preeminent abstract artists.

His return to figuration was disparaged and ridiculed when the paintings first came before the public in his now infamous 1970 solo exhibition at New York City’s Marlborough Gallery. Despite fierce criticism, Guston insisted on confronting some of the most difficult and pressing questions our society continues to face. These paintings, preoccupied as they are with the nature of the self and its relationship to evil, violence, and bigotry are destabilizing, disruptive, and precisely for that reason they cannot afford to be overlooked.

Born in 1913, the son of Ukrainian Jewish immigrants who fled extermination in the pogroms of 1905, Guston was no stranger to racial hatred which he would encounter firsthand growing up in Los Angeles. Ku Kluxers first appeared in Guston’s work of the early 1930s, including a 1932 mural based on accounts he had read of the trial of the Scottsboro boys, nine Black youths falsely accused of rape in Alabama in the spring of 1931. A terrifying and brutal depiction of a Klansman whipping a roped black man, Guston’s mural was desecrated, along with several others, by a group “led by the chief of the Red Squad [a unit of the Los Angeles Police Department that went after Communists and strikers].”

Neither was Guston a stranger to tragedy: despondent and reduced to rag picking, his father hanged himself from the porch, and was likely discovered by Philip who had his tenth birthday only three days earlier. Ropes and porches will emerge in paintings such as If This Be Not I (1945) and Porch II (1947), both included in the current exhibition. The figures in these paintings are compressed, and flattened against each other, accentuating the overall sense of claustrophobia. They are also evocative of the Holocaust: in the lower left of If This Be Not I, a figure wearing the striped pajamas of the concentration camp is laying on his back, his head turned so that he looks vacantly at us from over his right shoulder, while his right hand slumps lifelessly beside a discarded light bulb (one of his favorite motifs). In the figure’s left hand, he clutches a tin horn against his chest, perhaps suggesting an angel. The dangling rope of Porch II may refer to his father’s suicide; while a man hanging upside down, exposing the soles of his shoes, is an image that Guston will use in alluding to the Holocaust.

The early work demonstrates Guston’s mastery of a style informed by the great Mexican muralists (‘Los Tres Grandes’), the stylized forms of Giorgio de Chirico and Pablo Picasso, as well as the Italian Renaissance frescoes of Piero della Francesca, who painted “like a visitor to the earth… as though opening his eyes for the first time… without manner.” Guston in fact displayed Piero’s Flagellation of Christ (c. 1456-60) for much of his life: “I want to look at [it] when I have eggs and coffee in the morning or my drinks at night.” Something of Piero’s depiction of the violent flogging of Jesus is recognizable in a painting such as Martial Memory (1941), a scene of children fighting in costume (a theme to which Guston returned more than once): in this case, the children have paused momentarily, holding their weapons in the air, echoing Christ’s tormentors in the Flagellation.

Figurative painting was unequivocally set aside with the lush hues of Red Painting (1950), generally regarded as Guston’s first foray into pure abstraction, to which he would be wholly devoted for the next 16 years. Unlike colleagues including Jackson Pollok (with whom Guston attended high school in Los Angeles), Guston painted with short rapid brushstrokes, working extremely close to the canvas. The results were rich, and visually enticing tapestries of color with touches reminiscent of Turner and especially Monet.

“Decisions to settle anywhere are intolerable,” Guston would write, “[U]nless painting proves its right to exist by being critical and self-judging, it has no right to exist at all – or is not even possible.” Having achieved international recognition for his abstract paintings, Guston forsook critical acclaim by returning to figuration, but in an entirely new, almost cartoon-like style informed by the aesthetic sensibilities he developed as an abstract artist. Although derided when they first appeared, it is the work from this third phase – characterized by the extensive use of his signature pinks and recurring objects, such as light bulbs, nails, shoes, clocks, and paintbrushes – for which Guston would be chiefly remembered.

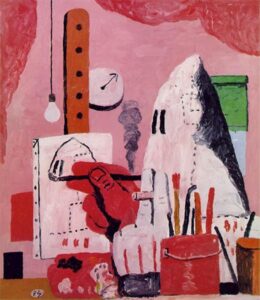

The Studio (1969), a meta-self-portrait (that is, a painting of the artist painting a self-portrait) unabashedly announced Guston’s move away from abstraction and his return to figuration and representationalism. The uneasiness that this painting generates arises from Guston’s decision to present himself in a Klansman’s hood, working at his easel, holding a cigar with his left hand and a paintbrush in his right, as he creates a self-portrait of his hooded persona. Guston would say of the many hooded figures to follow, “They are self-portraits. I perceive myself as being behind the hood. … I almost tried to imagine that I was living with the Klan. What would it be like to be evil?”

Guston’s Web (1975) is as disturbing as any of the Klan paintings – and, in fact, the over-sized eye of the bean-shaped head (standing in for the artist himself) is itself shaped like the hoods of his Klansmen. The red rim of the eye and three-day stubble is suggestive of sleeplessness, which can be understood here not only in terms of insomnia as a medical condition, but also as a crucial metaphor for modern subjectivity under conditions of late capitalism. Guston’s cyclops is vigilant without seeing anything – it is like the vigilance of one who is chained to being, contracted to exist and unable to escape the anonymous il y a (or ‘there is’) as the philosopher Emanuel Levinas would put it.

At the top of the painting, two black spiders spin their webs which partially ensnare Guston’s head if not his brain-shaped companion, a stand in for his wife Musa McKim, characteristically represented as a kind of sun rising or setting on the horizon. The spiders are weavers of time and fate – like the two women who busily knit their black wool, spinning the thread of each man’s life, at the entrance to the Company’s offices in Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness (1899).

Painting, Smoking, Eating (1973) is among Guston’s most recognizable works – and it is replete with the objects that variously inhabit the paintings from this period: cigarettes, light bulbs, the soles of shoes; and once again the single massive and vigilant eye of the artist’s oval-shaped head. In this case, the painter is lying in bed, smoking a cigarette, covered up to his chin by a blanket, with a plate of French fries propped on his chest. Behind him is a disordered and motley collection of shoes, a can of brushes, and a disembodied hand with its index finger pointing to the wall on which it has drawn a vertical red line. This image touches on the inevitable question, who precisely is painting in this picture? Is the artist painting in his imagination as he lays in bed? The disembodied hand marking the wall in blood invariably recalls the mystic hand which appeared before Belshazzar as he feasted in his palace, as related in the Book of Daniel, and famously depicted by Rembrandt in Belshazzar’s Feast (1635).

The prophet Daniel informs the Babylonian ruler that he was ‘weighed in the balance and found wanting’ – a stern judgement, and for Guston a kind of self-reproach with which he was not unfamiliar and that helps us to understand his departure from pure abstraction. As Guston would recall: “When the 1960s came along I was feeling split, schizophrenic. The war, what was happening in America, the brutality of the world. What kind of man am I, sitting at home, reading magazines, going into a frustrated fury about everything-and then going into my studio to adjust a red to a blue?”

A great deal of controversy preceded this exhibition, which will travel from Boston’s MFA to the Museum of Fine Arts in Houston, followed by the National Gallery of Art in Washington, and finally Tate Modern in London. In response to the “the racial justice movement that started in the US,” following the murder of George Floyd on May 25, 2020, all four institutions intended to postpone the exhibition until 2024, according to their joint statement – a testament to Guston’s ability to unsettle and even shock audiences over 40 years after his death.

Thankfully, the museums reversed their decision when a fierce backlash ensued. Guston’s daughter, Musa Mayer, pointedly observed: “My father dared to unveil white culpability… our shared role in allowing the racist terror that he had witnessed since boyhood, when the Klan marched openly by the thousands in the streets of Los Angeles… He understood what hatred was. It was the subject of his earliest works.” Indeed, one can hardly conceive of a more appropriate time to present the work of an artist whose paintings are not only a condemnation of evil, its banality and proximity, but a critical reflection on our collective responsibility for bigotry, antisemitism, and violence.

*

Sam Ben-Meir is a professor of philosophy and world religions at Mercy College in New York City.