By Rabbi Dr. Israel Drazin

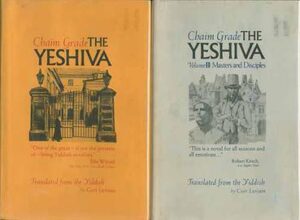

BOCA RATON, Florida — The Chaim Grade masterpiece, “The Yeshiva II,” is subtitled “Masters and Disciples” because it tells of dozens of lives of people in a manner unequaled by other writers. Each of the many people who populate this story has interesting and exciting lives that will fascinate readers. Grade is uniquely capable of telling their tales and weaving them into the impressive drama of the protagonist Tsemakh Atlas, thereby creating a drama much like the biblical coat of many colors given to a loved son. This drama undoubtedly deserves a Nobel Prize for Literature.

Sixty-eight people inhabit this novel set in six Jewish towns in Lithuania after the First World War, six cities that Tsemakh Atlas enters. One would imagine that it is impossible to remember and distinguish so many. But this notion takes no account of Grade’s genius. We have no difficulty. When they reappear, we recognize them as we would recognize and greet a family member.

Three stand out. There is Tsemakh. He is tall, handsome, and intelligent, but is conflicted. He spent close to twenty years in a Yeshiva that emphasized the teaching of Musar, Jewish ethics. Torah and Talmud were also taught but not emphasized. The ethics taught was harsh. It requires the individual to speak his mind unhesitatingly and, if necessary, embarrass people who do not act as the yeshiva teaches, even if it causes the other person to become angry. Tsemakh carries this idea to an extreme. He considers ethical behavior more important than other aspects of Judaism. He is unsure that God exists. He doubts that God answers prayers and helps people. He is confident that ethical behavior is more important than Torah laws because people are evil from birth and cannot become good unless they exert constant effort at self-improvement through ethical studies.

Yet, he feels driven to be a Rosh Yeshiva, the head teacher and mentor at a school for young boys. He signs a contract to marry a woman and leaves her because he sees she is sickly and her father will not fulfill his obligations under the contract. He feels very guilty for causing her distress. He marries instead a gorgeous non-religious woman who loves him dearly, abandons his religious practices, and accepts her family’s offer that he be a worker in a store. He also leaves her and his wealthy in-laws because he feels guilty about the woman he rejected and stopped being religious. He goes to another town and becomes a Rosh Yeshiva without changing his inner conflicts. He falls in love in the new town with a married woman who reciprocates his love because her husband is seldom home. Her husband travels from town to town asking for contributions for yeshivas.

Rabbi Avraham-Shaye Kosover, a renowned scholar and sage, is the opposite of Tsemakh. He suffered a similar betrothal deception. The woman to whom he was betrothed turned out to be much older than he understood and incapable of having a child. She is also very loud and outspoken and turns off many people. But unlike Tsemakh, he marries her. He treats her with dignity, although he does not love her. He acts respectfully to everyone and is highly esteemed by virtually everyone, even Tsemakh. He criticizes Tsemakh’s harsh ethical practices. He said, “Except for certain extraordinary instances when one must not look on and keep silent, we shouldn’t tell another person anything about his character and behavior until he asks us and until we’re certain that he has asked the question so as to improve his character and behavior. Even then, we shouldn’t tell him anything beyond his understanding and his ability to change.” He is convinced that Tsemakh is doing enormous harm to his students by his actions. He takes Chaikl out of Tsemakh’s yeshiva to save this intelligent boy. He makes Chaikl his student.

The third principal character in this novel is Chaikl. Readers should pay special attention to this boy. His father is interested in the Enlightenment, which questions many Jewish ideas, and encourages Jews to engage in secular studies. He disagrees with the approach of Rabbi Avraham-Shaye Kosover who felt that Jews must spend their lives immersed in holy books. He feels instead that Jews must not isolate themselves from the world. Chaikl’s mother, on the other hand, is very religious and wants him to become a rabbi. He is modeled on Chaim Grade, who left the Musar yeshiva and Jewish practices in 1932 at age 22.

The following is a small sampling of the dozens of other people whose stories are told in this novel. There is the crude tobacco merchant who tormented his son, a yeshiva student, and drove him to abandon Jewish practices. He refused to send his wife a divorce for fifteen years. She left the country, settled in Argentina, married another man, and lived in an adulterous relationship. She had children who were considered bastards by Jewish law. Although once prosperous, he turns himself into a beggar. He does not send his wife a divorce but goes from house to house begging for food, acting pious to impress others with his piety despite his terrible treatment of his wife and son.

Sroleyzer, a bricklayer, thief, fence, and a member of Tsemakh Atlas’s congregation, is approached to help solve the problem that arose when the local library gave secular books to the yeshiva students. Tsemakh and Rabbi Avraham-Shaye Kosover agreed that the library books must be stolen and burnt. Sroleyzer was paid to do so. The two were surprised at the uproar in the town when the books were taken. Demands were made to punish the person or persons involved in the theft. Tsemakh suffers greatly. Sroleyzer becomes a hero for claiming that he saved the books.

Elke Kogan, a quiet woman with a mental problem, becomes pregnant. She is unable to identify the man who raped her. The community feels confident that the culprit is Sheeya Lipnishker, a Torah scholar who teaches Judaism to local farmers, a man Elke Kogan admires.