By Donald H. Harrison

However, Baron told the Conservative congregation’s Men’s Club, Roosevelt did work behind the scenes to persuade countries in Latin America and the Caribbean to accept Jewish refugees.

Over 60 percent of the Americans polled at that time said they did not want any relaxation of the immigration quotas to help the beleaguered Jews, said Baron, professor emeritus of history at San Diego State University.

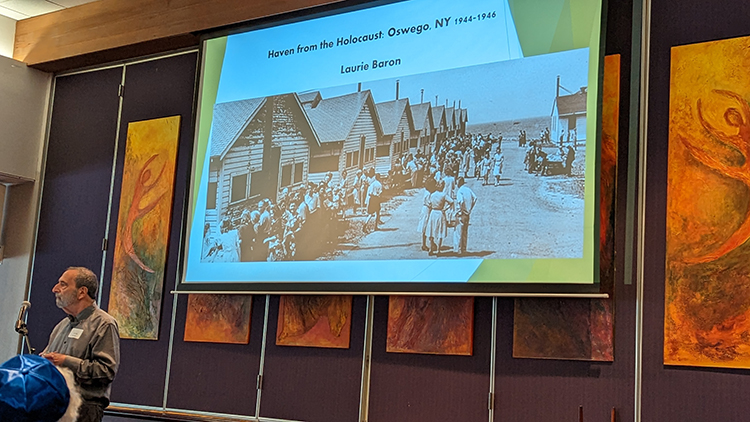

Baron, who also is the former director of SDSU’s Lipinsky Center for Judaic Studies, said that public opinion reversed during the late years of the war, and then, and only then, was Roosevelt willing to take approximately 1,000 refugees onto American soil at Oswego, New York, on the shores of Lake Ontario.

The former professor quipped that while Winston Churchill was known for his two-finger “V” for Victory salute, Roosevelt was known for his raised index finger testing the political winds.

The refugees were rescued from Italy, which came under German domination following the overthrow of Fascist leader Benito Mussolini.

More Jews could have been saved if Roosevelt had not been so concerned with losing his political support, Baron said. Just as Oswego had a military base where refugees could have been temporarily housed, so too did many other cities have similar bases.

The refugees were kept confined to Fort Ontario under rules administered by the same U.S. agency that was in charge of the internment of Japanese-Americans during World War II, Baron said.

Ironically, German and Italian prisoners-of-war who also were sent to the camps in the United States had more freedom than the refugees at Fort Ontario, most of whom were Jewish. The enemy POWs were allowed to work under supervision at necessary civilian jobs, whereas the refugees were not.

As a legal fiction, the refugees had not been permitted to enter the United States, Baron said. Just as produce and products can be held in an American “free port” on a temporary basis before going on to their American destinations, such was the case in 1944 of refugees sent from Europe to Fort Ontario. They, in essence, were being lodged in a “free port.” The reason for this fiction was to distinguish the refugees from immigrants, upon whom Congress had set quotas.

After Roosevelt died in 1945, President Harry S. Truman continued sequestering the refugees at Fort Ontario until deciding, while Congress was out of session, to permit the people interned there to settle in the United States.

First, however, they were required to go to Canada, fill out paper work, and then be admitted to the United States as postwar refugees.

Among those attending Baron’s talk was Rabbi Lenore Bohm, who had been the founding rabbi of Temple Solel and the first female pulpit rabbi to serve in San Diego County. She said that her grandparents were among the refugees who were temporarily lodged at Fort Ontario before eventually making their way to New York, where their son (the rabbi’s father) had been able to settle years earlier. Her grandparents were not very religious. By becoming a rabbi, she quipped, she was the “black sheep” of the family.

*

Donald H. Harrison is editor emeritus of San Diego Jewish World. He may be contacted via donald.harrison@sdjewishworld.com