Editor’s Note: This is the second chapter in Volume Two of Editor Emeritus Donald H. Harrison’s 2022 trilogy, ‘Schlepping and Schmoozing Along the Interstate 5,’ which may be purchased in its entirety on amazon.com and at speeches that Harrison makes to community gatherings.

Editor’s Note: This is the second chapter in Volume Two of Editor Emeritus Donald H. Harrison’s 2022 trilogy, ‘Schlepping and Schmoozing Along the Interstate 5,’ which may be purchased in its entirety on amazon.com and at speeches that Harrison makes to community gatherings.

‘Schlepping and Schmoozing Along the Interstate 5’: Exit 21 (SeaWorld Drive): Hubbs SeaWorld Research Institute

From SeaWorld Drive/ Tecolote Road exit of northbound Interstate 5, turn left (west) onto SeaWorld Drive. Take the Ingraham Street/ Mission Bay exit from SeaWorld Drive, careful to move into the left lane so you’ll get onto Ingraham Street. At the first stoplight, turn right at Perez Cove Way. Make a quick left into second driveway. Hubbs SeaWorld Institute is at 2595 Ingraham Street.

By Donald H. Harrison

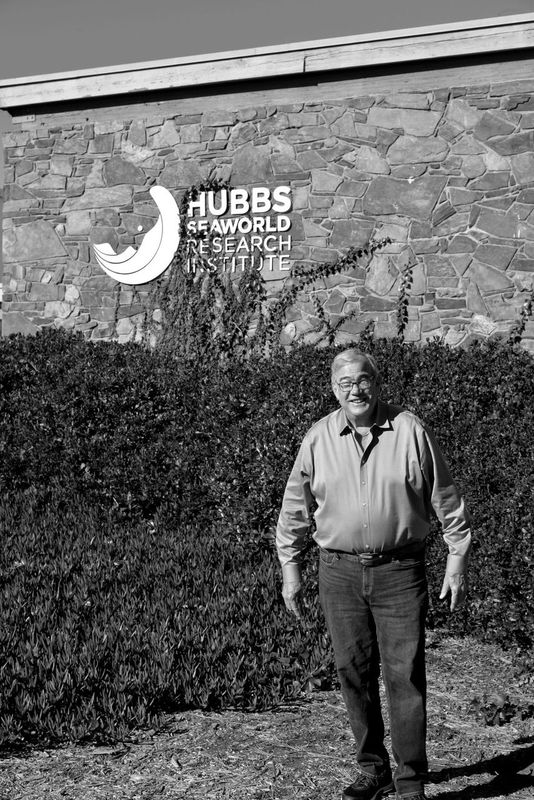

SAN DIEGO — Donald Kent is passionate about food. He cares about what he eats, what the fish raised at Hubbs SeaWorld Research Institute eat, and what he hopes Californians in particular, and perhaps Americans in general, will someday eat.

Kent, the President and CEO of Hubbs SeaWorld Research Institute, quips that he converted to Judaism because he liked blintzes and bagels that he was introduced to at the home of the parents of his future wife Cara Haas.

“The first blintze I had kind of put me over – it was so much better than Frito casserole or Jello with pineapple,” he joked during an interview at the research facility adjacent to SeaWorld.

In 1995, the Institute began construction of another facility in Carlsbad where white sea bass are now raised. The hatchery annually releases 100,000 white sea bass into the ocean. After learning how to grow and manage a species in more than 20 years of operation of that laboratory, the Institute now is embarked upon a far more ambitious and potentially far more impactful project with California yellowtail.

At the Institute’s main laboratory in San Diego, a converted 30,000-square-foot space that once was home to SeaWorld’s Atlantis Restaurant, Kent conducted me through laboratories to large, covered, temperature-controlled tanks in which yellowtail currently are being raised. California Yellowtail (Seriola dorsalis), although a member of the amberjack family, is often popularly referred to as Yellowtail tuna.

Kent’s idea is to vastly increase the supply of yellowtail in the eastern Pacific Ocean by raising them in a system of offshore pens from which they could be easily harvested and brought back to San Diego for processing. The Institute at the time of our interview was urging members of Congress, including a fellow Jew, Democratic Sen. Brian Schatz of Hawaii, to create laws that will govern permitting processes for construction of fish pens in federal waters. The pens that Kent has in mind would measure 30 meters across located in 200 feet of ocean about four miles off Pacific Beach.

One component of the project is to find protein sources for yellowtail to eat that are not from other kinds of fish. It doesn’t increase the overall population of fish if you must go out and catch tons of herring to feed yellowtail. When fish processing plants filet fish, the heads, guts, and tails are left behind. The scientists at Hubbs SeaWorld Research Institute are experimenting with grinding up these leftovers and mixing them with soybeans to create an alternative protein diet for the yellowtail. “With every fish species we work with, we are trying to develop different diets that use less and less fish in them, so you end up with a net increase in seafood as opposed to 1:1,” Kent said..

The current focus on yellowtail is because “it is a local species with an established market that is met with imports,” Kent explained. “When you eat hamachi at a sushi bar here, it is Japanese yellowtail; it is all flown in from Japan. So, why can’t we just grow it here? Put the jobs here. It costs $1 to ship a kilogram; that means we can grow it and sell it for $1 less making it more affordable so more people can eat it. It’s a real shame that seafood could become the rich person’s food unless you are willing to eat just tilapia, and even that is becoming expensive. We need to provide a better-quality protein for people at a lower cost without sacrificing the environment.”

Kent believes greater reliance on fish in our diets would greatly improve the global environment. Today, he noted, “we rely on beef, chicken, and pigs for our animal protein. Seafood is maybe 30 percent of our diet in the U.S. and most of that is being imported from somewhere so there is a carbon footprint associated with bringing it into the country. We only catch and grow 6 or 7 percent of the seafood we consume here. So, by bringing it in from somewhere it has a big footprint.”

“Another problem is that there is going to be another two billion people on the planet in 30 years and they’re [going to be] hungry,” Kent continued. “The more cows we grow, the more methane we produce, plus the conversion efficiency on cows is terrible. … It takes about 400 gallons of water for a pound of ground round. And then there’s methane production: a cow puts out about 50 gallons of methane a day, and this is fine if it is one cow, but when it is over 1.5 billion cows! And then you have to feed them. It is estimated for us to make up the difference in what we need in animal protein between now and 2050 will take two thirds of the area of South America for forage and grazing, so that isn’t the way to go.

“We can grow a yellowtail which has a much better conversion efficiency, has an excellent Omega-3 fatty acid profile – it doesn’t have the bad cholesterol; it has all the good Omega-3 fatty acids – and it doesn’t require any fresh water. If I grow it four miles out to sea and bring it in to the same seafood supply chain that we already have – in other words, take it to Chesapeake Seafood and let them process it and put it into the distribution system – it doesn’t have to be flown in and we’ve created 300 jobs doing it.”

He recalled that San Diego used to be the center of the tuna industry, but now seiners focus their activities in the western Pacific. “What is left here is a smattering – they catch a little bit of tuna hook and line. They catch sea urchins and lobsters, basically a very small operation. We do about $10 million a year in ex-vessel value from about a thousand tons of product landed. A thousand tons is what a good-size tuna seiner would bring in on one trip and they did two or three trips a season. There were 40,000 cannery and vessel maintenance jobs here that are all gone now. … What the Port of San Diego is interested in: we have a seafood industry infrastructure here but the amount of product that comes in and is sold really doesn’t justify the cost of what the industry needs. But if you had a farm designed to produce 4,000 to 5,000 tons a year, at least four times what all the commercial fishing does, its ex-vessel value would be $40 to $50 million per year and create 300 new jobs.

“It gives the guys at Chesapeake who process seafood more business. It gets the guys who fix boats more business. It creates additional ancillary jobs. So, there is a lot of socio-economic interest in it and my Institute’s role is to make sure that the biological and technological aspects of it are appropriate with ultimate respect for the environment.”

Kent credits former Republican State Sen. Larry Stirling (who later served as a Superior Court judge) with providing the impetus for the white sea bass hatchery in Carlsbad and the subsequent strides made locally in fish farming.

“One day Larry Stirling came by and said, ‘You know, I visited the fisheries laboratories in Eilat, Israel, and they’re doing this.’ I said, ‘Well, the Mediterranean is doing this all over. Eilat is unique because of the location [on the Red Sea] but if you go to the Mediterranean, they are growing sea bream and sea bass. It is an industry over there, growing branzino.’ … His parting words to me were ‘I’m going to create this program to get you the money to make this happen.’ So, he created that opportunity based on a visit he had to Israel.”

Kent built on a program that already had begun by SeaWorld Board Chairman Milton Schedd, who was a sports fishing enthusiast. Kent recalled that “we started trying it, and we started getting white sea bass, started learning how to do it, how big to grow them. A couple of years ago we got back a fish that had been out for 20 years. It was released from Dana Point, and it was caught off Palos Verdes by a kayak fisherman and it took him 40 minutes to land it. It was a 50+ pound fish. I like to think in terms of, ‘well, that fish for a good 17 years has been making baby white sea bass.’ [White sea bass don’t spawn until they are three-years old.] The whole idea is not to create a put-and-take fishery but to increase the size of the adult population so we can be self-sustaining.”

The white sea bass hatchery is “really a unique facility, the only thing of its kind on the West Coast dedicated to marine species, which are a lot different from trying to grow catfish or salmon,” Kent said.

“The reason that white sea bass needs to be enhanced is because we have captured too many of them. They knocked the red drum population in the Gulf of Mexico down by overfishing them and so now they are trying to rebuild that stock back up again. Well, when you do that with salmon, if you put a billion salmon smolts out in the ocean, you are lucky to get a million of them back. But if you put a billion salmon smolts in a pen and rear them up, you get almost a billion adult salmon back that you can feed people with. So, half the world’s seafood is now coming from farming. The white sea bass program created the opportunity for us to demonstrate how we can both catch and grow our seafood.”

Kent explained that the yellowtail and white sea bass projects are just two research areas occupying the attention of 40 Hubbs scientists in San Diego and Carlsbad, California, and in Melbourne Beach, Florida. “We did studies on how to clean sea otters if there is an oil spill. We did studies on the acoustics of marine mammals.”

Hubbs SeaWorld Research Institute is involved in numerous other projects. One of them, in collaboration with San Diego State University, developed a bioreactor to eat petroleum products as a way to clean up oil spills. Others looked at the effects on marine mammal populations of rocket launches from Vandenberg Air Force Base, California, and the impact on birds in Florida when rockets take off from Cape Canaveral. “We were up at Mono Lake looking at the effect of water diversion from the lake,” from which water is piped to Los Angeles. “We studied how it impacts the birds who migrate there. We did work on how ferry boats could avoid striking whales in Venezuela…”

*

Donald H. Harrison is editor emeritus of San Diego Jewish World. Next Week: Exit 21 (Tecolote Road): University of San Diego.