Editor’s Note: This is the fourth chapter in Volume 2 of Editor Emeritus Donald H. Harrison’s 2022 trilogy, “Schlepping and Schmoozing Along the Interstate 5.’ All three books may be purchased from Amazon.com, or at any of the lectures that Harrison delivers to groups around the county. Harrison may be contacted via donald.harrison@sdjewishworld.com

Editor’s Note: This is the fourth chapter in Volume 2 of Editor Emeritus Donald H. Harrison’s 2022 trilogy, “Schlepping and Schmoozing Along the Interstate 5.’ All three books may be purchased from Amazon.com, or at any of the lectures that Harrison delivers to groups around the county. Harrison may be contacted via donald.harrison@sdjewishworld.com

Schlepping and Schmoozing Along the Interstate 5, Vol. 2: Exit 22 (Clairemont Drive/ Mission Bay Drive): Mission Bay.

From northbound Interstate 5, turn left at Clairemont Drive/ Mission Bay Drive exit and follow to Mission Bay. At East Mission Bay Drive, turn right and follow to the San Diego Mission Bay Resort at 1775 E. Mission Bay.

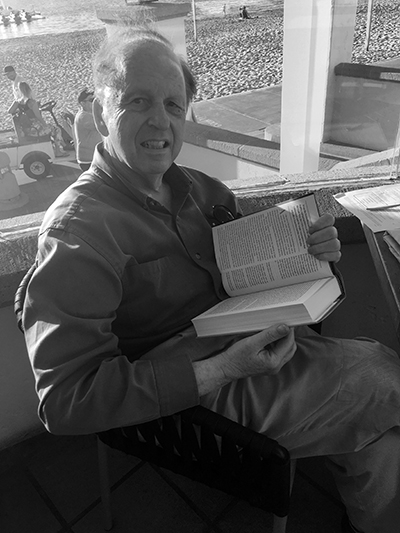

SAN DIEGO — For our interview, former California State Assemblyman Howard Wayne and I chose a table at the San Diego Mission Bay Resort overlooking a narrow band of beach alongside the blue waters of Mission Bay. The Bay is one of San Diego’s major water recreation areas. Over coffee, Wayne explained to me that water from the higher elevations runs off regularly into the Bay. Sometimes it’s rainwater; other times it is water from people watering their lawns, or hosing off their driveways, or washing their cars. This water heads downhill, picking up whatever debris and pet excrement may lay in its path. Eventually, the polluted water may find its way into a storm drain and then flow down to Mission Bay or to any of the beaches along the Pacific Coast.

SAN DIEGO — For our interview, former California State Assemblyman Howard Wayne and I chose a table at the San Diego Mission Bay Resort overlooking a narrow band of beach alongside the blue waters of Mission Bay. The Bay is one of San Diego’s major water recreation areas. Over coffee, Wayne explained to me that water from the higher elevations runs off regularly into the Bay. Sometimes it’s rainwater; other times it is water from people watering their lawns, or hosing off their driveways, or washing their cars. This water heads downhill, picking up whatever debris and pet excrement may lay in its path. Eventually, the polluted water may find its way into a storm drain and then flow down to Mission Bay or to any of the beaches along the Pacific Coast.

While most swimmers and surfers were aware that the waters of the beach and bay could become polluted after a heavy rain, few realized that the outflows of storm drains, even during dry months, could be dangerous to the health of swimmers and surfers. Wayne, himself, only learned this while he was campaigning in 1996 as a Democratic candidate in the 78th Assembly District, which then ran in a narrow coastal swath from La Jolla south all the way to the Mexican border. Donna Frye, who five years later would be elected to the San Diego City Council, was then the owner of a surfboard shop in Pacific Beach. When Wayne came to call on her, she asked him to follow her to the rear of her shop, where he could witness a storm drain discharging into the surf. Impressed, Wayne said if he were elected to the state Assembly, he would try to do something to remedy the situation. He did win, defeating Republican Tricia Hunter, a friend of California’s then Republican Gov. Pete Wilson.

Sworn in as an assemblyman in December 1996, Wayne promptly invited Frye and other environmentalists to his district office in the State Building on Front Street in downtown San Diego. For Wayne, who is Jewish, protecting beach users against toxins was an obvious example of tikkun olam – helping to make the world better. In a strategy session, the group decided that Wayne should introduce a bill in the Legislature that would do four things: 1) Establish standards for when waters would be considered unsafe for human contact; 2) Regularly test ocean and bay waters near storm drains; 3) Post information about polluted waters that might pose a risk to swimmers and surfers; and 4) Keep a record of where problem areas were located.

In February 1997, Wayne, Frye, and Scott Peters, an environmental attorney, publicized the introduction of the bill at a well-attended news conference at a La Jolla beach. Scott Peters would win a San Diego City Council seat three years later and subsequently serve on the Port Commission before being elected to Congress in 2012. The bill to provide information to swimmers and surfers was numbered as AB 411 – seen by Wayne as a nice coincidence because 411 is the telephone number Californians call for information. The Legislature at the time had a narrow Democratic majority, so narrow that to fill all the committee chairmanships, Assembly Speaker Cruz Bustamonte selected some promising freshmen legislators for prestigious positions. To Wayne’s surprise, he was tabbed to head the eight-member (five Democrats, three Republicans) Assembly Committee on Environmental Safety and Toxic Materials.

Wayne told Bustamonte that he didn’t have a background in biochemistry, to which the Speaker replied that consultants could advise him. When constituents asked him what kinds of subjects the committee handled, he’d quip, “Nothing important, just the air we breathe, the water we drink; that type of thing.” The subject of the bill required it to be referred to Wayne’s own committee for an initial hearing. After the committee unsurprisingly passed its chairman’s bill, it went next to the Committee on Local Government, which “was filled with ex-mayors and ex-city councilmembers.” Before it could be heard, Wayne thought it wise to narrow the bill so that testing of the waters would be only for such substances that might pose an immediate threat to human health. He thereby eliminated mandatory testing of substances that are environmental concerns but do not pose an immediate threat to human life. By narrowing the bill, Wayne reduced the potential cost of testing.

Nevertheless, the bill ran into some opposition from Republican members of the committee, who were concerned that it would impose unnecessary costs on some communities. The bill went next to the Appropriations Committee, where it was passed on a party-line vote. Then, the bill moved to the Assembly floor where the Democratic majority supported it and most of the Republican minority opposed it. Although the bill passed the Assembly, Wayne knew that unless something could be done to satisfy Republican critics, the bill would be in deep trouble when and if it reached Gov. Wilson for signature. He didn’t want to get it all the way through the Legislature only to see it vetoed by the governor.

The next step in the legislative process was a hearing in the state Senate’s Committee on Health. The bill passed 5-2 with opposition coming from the Republican side.

Before the bill could be heard in the Senate Appropriations Committee, Wayne asked that the committee postpone its scheduled hearing, delaying action until he could further amend the bill. At that point he met with Mary McDonald, an environmental specialist in the governor’s office, to see if the bill could be amended in such a way as to improve the chances of Gov. Wilson signing it into law.

Wayne had met McDonald earlier in the year following a hearing in the Assembly Natural Resources Committee on a request for more funds from the Department of Forestry (later called CalFire). While not opposing a measure to enable CalFire to pay its bills, Wayne had questioned the agency’s advocate about why CalFire continually underestimated its needs year after year. “Why don’t you just tell us what the bill is going to be, instead of hiding it when we are considering the budget?” he demanded. After the meeting, McDonald complemented Wayne on his cross-examination of the advocate. She had wondered about the same things.

Wayne and McDonald met again at a dinner conference on environmental issues where, by chance, they were seated across from each other. Wayne used the occasion to brief her on AB 411 and subsequently kept her informed on its progress. After he put the bill on hold, she and other members of the governor’s staff met with Wayne and environmentalists to discuss the bill. The two groups could not come to an agreement on the measure. However, Wayne and McDonald continued their discussions and came up with two mutually agreeable amendments.

First, the bill had included a prescription for how the testing should be done. It was agreed that California state scientists should instead decide the procedures. In agreeing, Wayne said, “I’m a lawyer, not a scientist. I don’t know what tests are appropriate. I am willing to yield to the experts with the understanding that there be no more than a 24-hour turnaround from when the samples were picked up until the testing results would be released. That was a 24-hour window when people could become ill and not know about the danger.”

The other amendment was that local governments would not be required to do the testing until such time as the state government appropriated money to pay for it. After the amendments were put in, the bill was heard and approved on a bipartisan vote in the Senate Appropriations Committee.

The next stop was the Senate floor. All the Democrats voted yes, as did most of the Republicans, except the most conservative. The spokesperson for the bill in the Senate was Bruce McPherson, a highly regarded moderate Republican who, like Wayne, represented a coastal area. The bill passed 28-7, with all negative votes coming from Republicans who were to the political right of Gov. Wilson.

Because the bill had been amended on the Senate side, it needed to return to the Assembly for concurrence in Senate amendments. It was adopted on a 75-2 vote with the two opponents being Republicans, ironically from the San Diego County delegation: Assemblymen Howard Kaloogian from Del Mar and Steve Baldwin from the East County. Baldwin was a member of Wayne’s Committee on Environmental Safety and Toxic Materials, but did not register a vote when the bill originally was heard in committee.

Not long after the Assembly concurred in the Senate amendments, the Legislature adjourned for the winter holidays. Wayne and his wife Mary Lundberg decided to visit the northeastern states of the country. These were the days before cell phones were common, so Wayne arranged for his legislative staff to leave voice mails on an office phone for him whenever there was news about any of his bills. “At the end of our trip,” Wayne recounted, “we were in Bennington, Vermont, and Mary and I had gone out to dinner. We came back, called back, and found out that AB 411 had been signed. By that time the town was shut down, so we went to the candy machine, bought a Baby Ruth and split it, and that was our celebration!” After he returned to Sacramento, he purchased for his car a personalized license plate bearing the letter and number combination AB 411.

Still, the matter was unresolved. Unless Wayne could get an appropriation to pay for the testing, the bill would not go into effect. He was able to persuade his legislative colleagues to put money in the state budget to determine appropriate testing procedures as well as for a fund for local governments to draw on for future testing.

There still was more to do.

If problems were found at the outflows of certain storm drains, Wayne wanted those problems to be remediated rather than simply informing swimmers to stay away.

Assemblyman Mike Machado, a Democrat representing agricultural San Joaquin County, had proposed a major water bond measure, which required a two-thirds vote of the Legislature to be placed on the ballot for voter approval.

Wayne asked Machado to include $90 million for remediation projects along the coast – an idea that Machado resisted, arguing that additional expenses might turn voters off. Wayne, in turn, argued that unless there was something in the proposal to benefit coastal areas, he and other legislators representing such areas would not vote for the bill. So, Machado acquiesced. Meanwhile, Assemblywoman Denise Ducheny of San Diego was able to earmark $3 million of that $90 million for an unrelated project, but that still left $87 million for fixing trouble spots. The bond was approved by the Legislature and enacted by the voters.

So, what was the upshot?

“The number of beaches that were posted began to decline as people paid attention,” Wayne responded. “San Diego beaches, other than Imperial Beach (which is impacted by sewage runoff from Tijuana, Mexico) got very positive ratings, with fewer people becoming ill.”

“People care about beaches,” Wayne summarized. “I represented very diverse communities, La Jolla and Imperial Beach. What do they have in common? The beaches, the water.”

Although our discussion about AB 411 had run its course, Wayne shared with me that he has a special feeling for the immigrant families in Imperial Beach and other cities at the southern end of his district.

He and his brother Bob were grandchildren of immigrants and were the first generation in their family to go to college. They both went on to graduate from law school. Howard earned his undergraduate degree at San Diego State University and his law degree at the University of San Diego. He worked in the office of the state attorney general before and after his three terms in the state Legislature. His brother practices law in Seattle, Washington.

Their father, William Wayne, was among the founding members of the now defunct Conservative Congregation, Beth Tefilah. He was partners with Holocaust survivor Lou Dunst in the Logan Department Store, where William Wayne worked 12 hours a day, six days a week. “He never had the time to be really involved in anything other than his work,” his son said. “I think he had just one dream in his life – I tear up over this – that his two sons would get an education and make something of ourselves. He sacrificed himself to get his kids educated.” William Wayne died at the age of 60.

One year while he was still in the state Assembly, Howard Wayne gave a speech to Hoover High School students as the school’s alumnus of the year. He told the students that “they had a great public school system in San Diego and that I was fighting in the Legislature to make public colleges affordable because I wanted them to have opportunity. I told them two things. One, when you get that achievement, you have an obligation to make sure that the ladder of opportunity is there for those who are after you.” In a football analogy, he said he also told them “their teachers were coaches, their parents and grandparents cheerleaders, and they were on the field and were the captains of their team. It was really on their shoulders to take advantage of this and use the opportunity.”

One year while he was still in the state Assembly, Howard Wayne gave a speech to Hoover High School students as the school’s alumnus of the year. He told the students that “they had a great public school system in San Diego and that I was fighting in the Legislature to make public colleges affordable because I wanted them to have opportunity. I told them two things. One, when you get that achievement, you have an obligation to make sure that the ladder of opportunity is there for those who are after you.” In a football analogy, he said he also told them “their teachers were coaches, their parents and grandparents cheerleaders, and they were on the field and were the captains of their team. It was really on their shoulders to take advantage of this and use the opportunity.”

*

Donald H. Harrison is editor emeritus of San Diego Jewish World. He may be contacted via donald.harrison@sdjewishworld.com