Editor’s Note: This is the seventh chapter in Volume 2 of Editor Emeritus Donald H. Harrison’s 2022 trilogy, “Schlepping and Schmoozing Along the Interstate 5.” All three books may be purchased from Amazon.com or at any of the lectures that Harrison delivers to groups around the county. Harrison may be contacted via donald.harrison@sdjewishworld.com

Editor’s Note: This is the seventh chapter in Volume 2 of Editor Emeritus Donald H. Harrison’s 2022 trilogy, “Schlepping and Schmoozing Along the Interstate 5.” All three books may be purchased from Amazon.com or at any of the lectures that Harrison delivers to groups around the county. Harrison may be contacted via donald.harrison@sdjewishworld.com

Schlepping and Schmoozing Along the Interstate 5, Vol. 2: Exit 26A (La Jolla Parkway): Congregation Adat Yeshurun

From northbound Interstate 5, follow La Jolla Parkway exit to the first right turn, which takes you onto La Jolla Scenic Drive North. The synagogue at 8625 La Jolla Scenic Drive north is on the right-hand side.

LA JOLLA, California – When South African-born civil engineer Brian Marcus relocated from his first American home in Dallas to La Jolla, it was just in time to volunteer his help for three major projects for Congregation Adat Yeshurun. First came the building of the sanctuary and campus of the Orthodox congregation. Next came the completion of a mikvah on the property. And third came the most complicated task of all: erecting an eruv.

LA JOLLA, California – When South African-born civil engineer Brian Marcus relocated from his first American home in Dallas to La Jolla, it was just in time to volunteer his help for three major projects for Congregation Adat Yeshurun. First came the building of the sanctuary and campus of the Orthodox congregation. Next came the completion of a mikvah on the property. And third came the most complicated task of all: erecting an eruv.

Oh, the engineering was relatively simple, said Marcus. What made the project complicated was that the residents of La Jolla, a community with a documented history of antisemitism, fought against allowing an eruv in their neighborhood every step of the way.

In a November 2020 blog for the Times of Israel, Jessica Levine Kupferberg recalled that after she and her doctor husband Duvy moved to La Jolla, “we were desperate for an eruv. Without one, each time we had a baby, I was tethered to home on Shabbat while Duvy attended Shul. We could not easily go to friends’ houses for a meal, or on a Shabbat stroll with a stroller, and when Duvy did a weekend shift working at the hospital, I felt utterly isolated. (I feel now that this was boot camp for the COVID era, as I learned how endless a stretch of time can feel when you are segregated from family and friends.)”

Her husband, Dr. Duvy Kupferberg, became president of Adat Yeshurun at the time and was instrumental in getting the city approval for the eruv. The family subsequently made Aliyah to Israel.

Jewish law prohibits working on the Sabbath. Carrying outside of the home is considered a form of work, whether what is carried is a package or a child. An eruv symbolically extends the home to an enclosed space surrounding the neighborhood, thereby greatly expanding the area within which someone might carry a baby or push a stroller.

La Jollans fought over the eruv through much of 2006. Fifteen years later, when Marcus was serving as president of the congregation the battle still was remembered with some bitterness.

“Obviously they couldn’t oppose it on religious basis, so they had to have other kinds of reasons why this was supposedly terrible,” Marcus recalled. “They included unsightliness, that it was going to be a blight, and secondly that it was going to be an environmental hazard to the birds, and birds would be flying into these invisible wires and killing themselves.”

While those were the “official” reasons for the opposition, other far more nasty and prejudiced reasons surfaced in letters-to-the-editor and at required community meetings preparatory to the issue going before the San Diego City Planning Commission and later to the San Diego City Council.

The San Diego Union-Tribune reported in February 2006 that one opponent said, “If this is approved, obviously we’re going to have a Jewish community. I don’t want to live in an all-Jewish or all-anything-else community.” Another opponent characterized those seeking the eruv as “religious fanatics.”

In a letter to the La Jolla Light, a writer described an eruv as the boundary line of a shtetl. The writer went on to ask: “What happened to the concept of diversity? Did non-Semitic residents with homes within this eruv not have a choice in becoming part of this Jewish shtetl? They moved into the village of La Jolla and not into a Jewish shtetl. Did these residents vote on joining a shtetl within an eruv?”

With most community groups recommending against the eruv, the issue went to the City Planning Commission which two years before had approved an eruv in the neighborhood near San Diego State University where Beth Jacob Congregation is located. The Planning Commission followed precedent, giving its approval both to the La Jolla eruv and to another one that had been sought by Chabad of University City, located several miles to the southeast.

To satisfy La Jolla opponents who were worried about bird safety, it was decided that reflective tags should be attached every five feet in those places where monofilament was used to connect natural barriers.

Opponents led by the La Jolla Community Planning Association decided to appeal the City Planning Commission’s decision to the City Council. At that meeting, the Council decided that the reflective tags were not necessary—in fact would be ugly—so instead instructed Congregation Adat Yeshurun to report to city officials any instances of bird deaths because of flying into the wires.

“In the 15 years since, have any birds died?” I asked Marcus.

“Not one,” he responded.

Councilman Jim Madaffer, who represented Del Cerro, San Carlos and Tierrasanta, expressed his displeasure with the opponents. “The Chabad eruv [in University City], there was no incident, no complaints,” he said. “Then again, we’re talking about La Jolla here … This appeal and debate totally amazed me. I’m sorry, but I think there are still folks in La Jolla who simply don’t like folks of the Jewish faith. This is strictly a public-use issue. This is poles and a line, and all I can say is, ‘Get over it.’”

Historically, many property deeds in La Jolla contained covenants and restrictions against selling to Jewish purchasers. Even after such restrictions were ruled unconstitutional, La Jolla real estate agents maintained an informal protocol for turning away Jewish buyers. In the 1960s, the University of California decided it would build a campus within the City of San Diego. (La Jolla is a wealthy part of San Diego.) Administrators who knew the university would likely hire some Jewish faculty members informed La Jolla real estate interests that unless the discriminatory and illegal practice was abandoned, the campus would not b built in La Jolla. Knowing that having a campus of the University of California would be a spur to very lucrative business, the real estate agencies finally complied.

Scott Peters, who was then a councilman representing La Jolla and later became a member of Congress, took issue with Madaffer. “It’s not fair to say nothing’s changed in La Jolla,” he commented. “If you look at the list of community leaders in La Jolla, Jewish leaders are prominent on that list. I can’t say that in any deliberation of a public issue there’s not some prejudice, but I think that was not the motivation.”

Councilwoman Donna Frye, who represented coastal neighborhoods south of La Jolla, also defended the opponents: “A lot of the people who spoke today, I know very well. It’s hurtful to hear these things about them not liking Jewish people.”

That said, the Council voted unanimously in favor of permitting the eruv to be constructed.

*

The area including hills and canyons that the eruv encloses variably has been estimated t between 6.5 and 8 square miles. Marcus sad that going through the permitting process cost Adat Yeshurun more money than building the eruv itself.

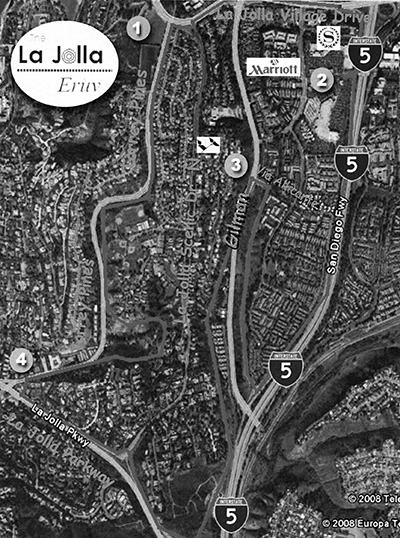

“In Dallas, you had telephone wires and electrical wires to define the area,” he recalled. “Here we don’t have overhead electrical wires, but we were fortunate that an eruv is not only defined by a string. It is also defined by inaccessible slopes or fences or hedges. So, it turns out that all of Interstate 5 has a fence alongside it, so that is perimeter demarcation of the eruv. The big challenge in building an eruv is making sure that the perimeter is a continuous, uninterrupted boundary. Basically, the Adat Yeshurun eruv perimeter extends from the I-5 to La Jolla Village drive down to Gilman and then it follows the ravine of Gilman, jumps over to the other side of the ravine, and covers all of this mesa, including the shul.” (See accompanying map.)

Three Jewish institutions are within the eruv: Congregation Adat Yeshurun (Orthodox), Congregation Beth El (Conservative) and the Hillel House serving the University of California San Diego.

Workers from the Urban Corps filled the gaps among the various natural features, fences, retaining walls, and so forth by stringing a little less than 5,000 feet of 200-pound nylon fishing lines across existing street poles or on newly constructed poles, 15 feet tall, installed for the purpose of the eruv.

The congregation’s longtime spiritual leader, Rabbi Jeff Wohlgelernter, who since has retired, brought in a consulting rabbi, whose halachic specialty was the laws covering eruvim.

“It was kind of interesting,” Marcus recalled. “It was a bad traffic day and he had to get here from Los Angeles. He was supposed to get here at 2 p.m., because he wanted to walk the entire area before he gave it the stamp of kashrut. He only got here by 4 p.m. and it was getting dark by 6 p.m. We were out there with flashlights until 8 p.m. or 9 p.m. with two rabbis, including the inspecting rabbi and myself clambering up hillsides. It was one of the more memorable moments.”

More recently, as the San Diego Association of Governments (SANDAG) was planning the now completed northern extension of the San Diego Trolley from Old Town San Diego to UC San Diego, Marcus said, “I knew from looking at preliminary plans that it would potentially impact our eruv. So, I reached out to them. We ended up going to a couple of meetings with their consultants at a big conference table at SANDAG with me and Rabbi Jeff (Wohlgelernter) explaining what an eruv is and why it is important. It ended up being put into the environmental impact statement for the entire project and put into the construction documents that the contractor is to always maintain an eruv during construction. During the entire 18 months of construction, no one knew why at the gates to the construction site they had a nylon filament with two 15-foot poles on either side of the gate with little reflecting tags on the line, so the truck drivers knew not to bust the wire! That part of the eruv was maintained by the general contractor throughout the construction of the trolley line!”

I met with Marcus on a Wednesday, the day a weekly inspection of the eruv is conducted in advance of Shabbat. He drove me around the eastern part of the boundary line. Another congregant had already inspected the western portion.

I met with Marcus on a Wednesday, the day a weekly inspection of the eruv is conducted in advance of Shabbat. He drove me around the eastern part of the boundary line. Another congregant had already inspected the western portion.

The eruv was intact, but if there had been a break, he said, the congregation would have it fixed during the week. Since the eruv was erected, said Marcus, “we fortunately have been able to get it fixed without anyone knowing that it was down.”

*

Donald H. Harrison is editor emeritus of San Diego Jewish World. He may be contacted via donald.harrison@sdjewishworld.com