By Donald H. Harrison

SAN DIEGO – The judges at the FIRST World Robotics Competition held April 19-22 in Houston, Texas, were mighty impressed with the looks of “Jerome the Giraffe,” a San Diego robot manufactured at Patrick Henry High School. The usual nickname for Patrick Henry teams is the “Patriots” but the robotics club made a slight change in the name. Their team is the “Patribots.”

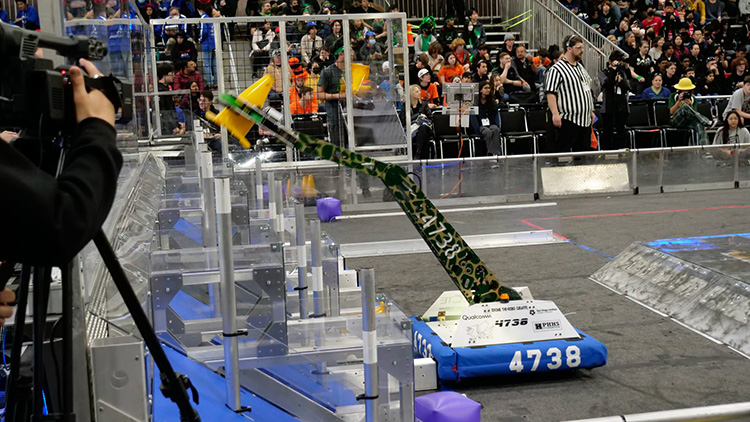

Naming the robot “Jerome” was a bit of alliteration because with a crane like appearance, it looked something like a giraffe. Building on that theme, the 25 to 30 students who regularly participate in club activities, painted Jerome with giraffe-like patterns in green and gold, which are the high school’s colors.

Benjamin Broudy is a graduating senior who served as the Patribots’ director of engineering. The son of Abe and Pam Broudy, he was a co-recipient during the last Jewish High Holy Days of a “Youth of the Year” Award conferred by the Men’s Club of Tifereth Israel Synagogue.

Broudy said the judges at the world competition awarded the Patribots the “Imagery” award, based mainly on how good Jerome looked, but also based on the uniforms worn by the “drive” team and the “pit” team, as well as supporters in the stands of the George R. Brown Convention Center in Houston.

“The main part is how the robot looks, having it look very clean and elegant,” Broudy said. ‘The reason we won was probably a combination of our drive costumes, our theme, which was a jungle safari type of thing, the robot being painted like a giraffe, its clean lines, and all the wires tucked in very nicely, so it looked very professional.”

Around the world, 3,300 teams competed to win an invitation in FIRST’s world competition. FIRST is an acronym: “For Inspiration and Recognition of Science and Technology,” an organization founded in 1989 by Dean Kamen. He is the inventor of the Segway PT, described on Wikipedia as “an electric, self-balancing human transporter with a computer-controlled gyroscopic stabilization and control system.” Eventually, 974 teams from 59 countries competed across three levels of competition, 620 of those teams at the high school level. Organizers said there were approximately 18,000 students altogether at the competition.

Broudy said the object of this year’s competition was to have the robots place cones and cubes on a three-dimensional grid. “The cones may be placed on either the high, mid, or low levels, and they are placed on poles except for the low level which are placed on the ground. The cubes are placed on a shelve.”

The drive team has five members, Broudy said, “three who stand behind the glass during the actual competition. One is driving the robot, the other is operating it, and the third one is the drive coach. There are two team members on the other side of the field who “hand out cones and cubes at the sub-station or loading zone. There is also a technician who drives a cart around and holds the supplies while the match goes on. The pit crew is the group of people who are working in our repair area where we fix the robot.”

The first several days were taken up in qualification matches in which the Patribots competed against other teams. They won all those matches, entitling them to pick two other teams with which to form an alliance to compete in elimination matches. Based on the rankings of teams the Patribots had faced in the qualification matches, they chose to ally with one team from Hawaii and another from Tlalpan, a Mexico City suburb.

Broudy said that most members of the Mexican team spoke good English and “our drive coach is fluent in Spanish,” so there were no problems communicating. As the captains of the alliance, the Patribots decided that its members and those of the Hawaiian team would be responsible for placing the cones at the high and mid-levels, while the Mexican team members would focus on the lower level as well as on some of the cubes.

“We did very well, our highest match that we had ever done,” Broudy related. “We filled out the entire grid as well as putting extra pieces on, which is called super-charging, so we went above and beyond.” In total, the robots placed 28 pieces—most of them cones.

That was good enough to place overall 59th meaning that the Patrick Henry team scored within the top 2 percent of all the competitors in the world.

The matches last only 2 ½ minutes. The first 15 seconds, the robots act autonomously according to their programming, and over the next 2 ¼ minutes, team members take control.

Teams with higher scores “might have had faster cycle time where they could pick up a piece and place it quicker,” Broudy speculated. Perhaps to improve Jerome the Giraffe, the Patribots “could change the gear ratio, as well as getting more driver practice.”

It was when the team was eliminated, and cleaning out the pit, that it was announced that Jerome had won the imagery award for its division. “We had been so excited to be in the eliminations and then we won the award,” Broudy said. The team received a trophy with three acrylic poles, one a square, one a triangle, and one a circle, with a plaque that said: “Curie Division: Imagery Winners.” The Curie Division was named for double Nobel Prize winner Marie Curie, who was a pioneer in the study of radiation.

The Imagery Prize and the 59th in the world ranking were the payoffs for two months of work in San Diego where the team spent 50 hours a week – “more than we spent in classrooms’ – developing and perfecting the robot.

They celebrated on Sunday, April 23, by visiting the Johnson Space Center in Houston, site of the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA)’s mission control. “We all found it extremely cool,” Broudy said. “NASA is one of the main engineering organizations; it was really awesome to see. We walked into a warehouse with a giant rocket in it and it was amazing to stand next to it.”

Some of the team members have picked colleges where they can study aerospace engineering, but Broudy is going a different way. He chose Cal Poly San Luis Obispo where he will major next semester in microbiology. “I really enjoyed my AP (Advanced Placement) Chemistry and AP Biology courses,” he explained.

Robots will thereafter be a hobby. “I probably will join a team at Cal Poly SLO that makes Formula-1 race cars,” he said.

So, what will happen to Jerome the Giraffe, whose looks so impressed the judges in Houston?

“It will be in the shop over the summer,” Broudy replied. “There probably will be people who will work on it. Then, in the beginning of next year, in the fall, there will be off-season events that use this year’s game to train new team members and to get people back into the groove of robotics. It will go to at least one, if not two or three, off-season events to compete there and hopefully win some awards and maybe an entire event.”

An entirely new robot will be built from the ground up for next year’s competition, so there will be no further use for Jerome after that.

Couldn’t Jerome be placed in a trophy case somewhere on the Patrick Henry campus?

“That would be nice, but it usually just stays in the maintenance area with the golf carts,” Broudy said. “We have quite a few robots that are in a line back there, collecting dust. It would be nice to have a display area for them because this is the third robot that has gone to the world competition.”

*

Donald H. Harrison is editor emeritus of San Diego Jewish World. He may be contacted via donald.harrison@sdjewishworld.com