By Donald H. Harrison

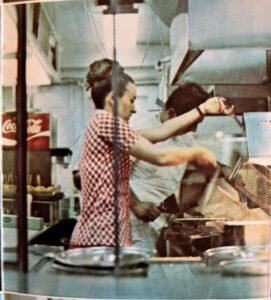

CARLSBAD, California – One thing is for certain when Chabad of La Costa has its gala fundraising dinner on Wednesday, August 9. They absolutely won’t let in-house caterer Sheila Lebovitz anywhere near the kitchen. They want her seated at a table with other guests. After all, she is the honoree!

So, if not her, who will do the cooking for the fundraiser? I asked the inveterate caterer and restaurateur.

“We have a staff that is pretty much in-house that I have been training for a while, and I have one or two of my old restaurant workers who will be coming in to help,” Lebovitz responded. “They said I am banned from the kitchen for the night.”

Cooking is Lebovitz’s world. The kitchen from which she has been banished, for that one night only, officially has been named “Grammy’s Kitchen” in honor of Lebovitz, 85, who is called “Grammy Sheila” by the nine children and 15 grandchildren of Rabbi Yeruchem Eilfort and Rebbetzin Nehama Eilfort, as well as by other younger members of the congregation.

Asked what will be served at a gala dinner honoring a caterer, Lebovitz said there would be five stations, all with appropriate side dishes to accompany the main servings. One is a carving station for turkey and ribeye steak. Another will be a cheese-less Mexican food station. Yet another will be an Italian food station, serving osso buco. A fourth will be “my corned beef, and they are letting me make that, but I am making it in advance.” The fifth station will be Shor Habor hotdogs – and therein lies a nostalgic salute to an important part of Lebovitz’s life.

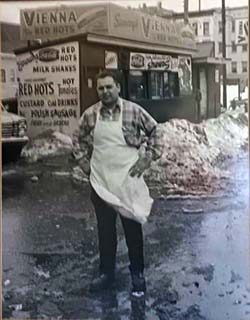

Lebovitz and her late husband, Norman, or “Normie” as she likes to refer to him, had a chain of 39 hot dog stands named “Lemmy’s” – the name selected because Chicagoans had a habit of saying “Lemme have a hot dog!” Lebovitz, who earned a degree in arts and design from a Chicago art school, designed a self-contained mobile hot dog stand, measuring 18 by 10 feet, that, like a motor home, could be hooked up to electricity, water, and sewage lines. She and her husband had them placed throughout metropolitan Chicago. Before that, from the time he was a young teenager, Norman ran another hot dog stand called Sammy’s.

The various branches of the United States military liked the mobile food stand design, so Lebovitz had them manufactured for dozens of bases both in the U.S. and abroad. “We would deliver them, set them up, and teach the people how to operate them,” she recalled in an interview. The military would move the coaches around their bases, at the time preferring to do their own cooking rather than bringing onto the bases fast food chains as they do today.

While the hot dog stands were accepted in most areas of metropolitan Chicago, Lebovitz recalled one alderman who wouldn’t approve the placement of a coach in his district unless the Lebovitzes made him a partner in that facility. He told Norman that “everyone needs a godfather.” Norman responded that, “I have one father that I support; I don’t need a godfather.” The Lebovitzes took the matter up with others at City Hall, including the vice mayor. “If Normie wanted something, he would fight tooth and nail for it,” Lebovitz said. A lawsuit was filed, and eventually the Lebovitzes got the spot they wanted, she said.

Norman decided that Lemmy’s should make its own pickles, so he started a side business in Mexico growing the small bumpy variety of cucumbers known as gherkins. He named the company Papa’s Pickles. The Vienna Beef company, from which the Lebovitz family obtained their hotdogs for Lemmy’s, purchased these pickles from the Lebovitzes, and eventually asked Norman to bring that business into their company, making him a vice president of Vienna Beef.

The Lebovitzes allowed the managers at the hotdog stands to acquire many of their respective locations, with Sheila Lebovitz retaining a few of the stands for her personal management. On one occasion the Vienna Beef Company asked their vice president to travel to California to deal with a customer who owed them lots of money.

In the process, Norman fell in love with San Diego and “decided he would give up his Vienna vice presidency—which to this day I could kill him for—and stay in California,” Lebovitz related. “That was in 1984 and I didn’t actually move here until 1987. He had a midlife crisis. I sold the stands in Chicago.”

In 1985, Norman opened a new restaurant in La Jolla called Sluggo’s, which became one of the first sports restaurants in San Diego County. “Normie and I are very avid sports fans,” she said. “We had satellite dishes and we would have all the Cubs games, Bears, Bulls, and Blackhawks, and we had huge crowds of people to watch the games.”

What about the White Sox? I asked innocently.

“Not them, ever,” Lebovitz said. “Just the Cubs.”

One day the National Football League announced that to watch out-of-the-area football games, people and establishments would have to purchase tickets via Direct Television. “They decided no more satellite dishes, you had to take cable,” Lebovitz said. “We started a group called the Association for Fans’ Rights, and he fought the NFL and he won. He did that on our nickel, our money.”

Sluggo’s grew to a chain of six restaurants around San Diego County, and continued until the time that Norman became ill and eventually died in 2014 – 54 years after their wedding. The Sluggo restaurants, with all their Chicago sports memorabilia, were closed.

Even though Norman left its employ, the Vienna Beef Company last November honored him and Sheila, recounting in their Chicago-based Hall of Fame the family’s involvement in Sammy’s, Lemmy’s, Sluggo’s, and Papa’s Pickles.

It was the pickle business that first brought the Lebovitz family into contact with Rabbi Eilfort. A cousin of Norman’s is Dr. Michael Lobatz, a neurologist who was an active member of Congregation Beth Am. Introduced to Rabbi Arthur Zuckerman of that congregation, Norman asked if he could be a mashgiach for Papa’s Pickles, which name Vienna Beef permitted Norman to reclaim. Zuckerman recommended that an Orthodox rabbi, such as Rabbi Eilfort, be contacted instead.

The year that Dr. Lobatz’s mother died, Lebovitz realized that there was no place that could cater kosher food for a shiva house. She decided to build a kosher kitchen at the company’s warehouse in Barrio Logan, at 25th and Crosby. “We had a big room there that we koshered, and we put in our own equipment,” she said. “Yeruchem was the mashgiach and Nehama baked challot, which we also sold to Ralph’s.”

Another enterprise was Sheila’s Café, a sit-down, tablecloth, kosher restaurant located in the Clairemont neighborhood of San Diego. Although it was the only such establishment south of Los Angeles, it didn’t garner sufficient patronage from local Orthodox families, who continued to travel to Los Angeles for their family functions. As for non-Orthodox Jews, Lebovitz said, “there were enough Jews, but not enough people willing to spend the money. They don’t support each other here, truthfully.”

Rabbi Eilfort was very young when his mother died in an automobile accident. When his oldest child, Elia Eilfort was born to him and Nehama in 1990, the rabbi’s father, David Eilfort, insisted that Elia and all subsequent Eilfort children should have a bubbe in California. “That’s how I became Grammy Sheila to all his children,” Lebovitz declared. Elia today is a Chabad rabbi headquartered in neighboring Encinitas.

Lebovitz has biological grandchildren in Chicago. In addition, the children and grandchildren of the Eilfort clan “call me Grammy,” Lebovitz said. “Three years ago, when I flatlined, they were all there, my biological and my Eilfort grandchildren to keep me going through the whole trauma. I died May 14, 2020—for 28 minutes.”

She was at a hospital to have surgery for spine compression, “but they never got to that part. I died first. The rabbi was the first person whom they called at 6 a.m. He was at Scripps in 10 minutes and all the hospitals were locked down because of COVID. He went to the hospital as my clergyman and –the doctors told me this, not the rabbi, who is too modest—he told them to keep working, don’t stop, and they did chest compressions. He said to me, ‘You’re not leaving, we need you here’ and he made them keep doing it, and I came out of it. I was intubated and I was in the hospital for a month.” This was followed by a 17-month rehabilitation period at home where (because of COVID), “I was in the house by myself, except for the nursing staff. I had to have all kinds of therapy. They had to teach me how to talk, how to walk, how to swallow. When you flatline like that, your brain goes down and you have to learn it all over again.”

That was the kind of devotion that Rabbi Eilfort had for Lebovitz and her husband, a devotion that was returned. When Norm died, Eilfort accompanied the family back to Chicago, and conducted the funeral in subfreezing weather. The ground was so frozen, Lebovitz said, that cemetery workers had to use dynamite to blast open a grave for her husband. “The rabbi is the most loving, caring, honest person on the face of the earth,” she said. “I am not a Chabadnik, I’m an Eilfortnik!”

Although Lebovitz lives in Rancho Bernardo, she drives 50 miles roundtrip at least four times a week to Chabad of La Costa in Carlsbad. There she caters kosher food for individuals and wedding parties who stay at the nearby Omni Hotel, and also cooks meals for synagogue kiddushes and celebrations, as well as soup and challah for delivery to shut-ins.

Personally, Lebovitz is not shomer Shabbos – she’ll drive on Shabbat for example, and eat nonkosher food at restaurants—and sometimes rues that she is not an observant Jew. Rabbi Eilfort remonstrates with her: “Don’t say that, you observe everything you can. Your heart makes you an observant Jew.” Lebovitz says whether she is 100 percent observant or not, “I am dedicated to being a Jew 100 percent.”

Rabbi Eilfort says of Lebovitz: “She has been a Jewish activist her whole life. Her Judaism is the core of her identity. She is also a fiercely patriotic and proud American citizen who loves this country and the opportunities it has afforded the Jewish people. Any person who walks in, walks out as Grammy Sheila’s best friend. She finds a way to connect to everyone and she truly cares about everyone – and that is not an exaggeration. She is in her eighties, but has boundless energy. In fact, when we do our barbecues, she won’t let anyone else at the grill. In her own way, she is kind of a food snob, and I mean that in a loving way.”

Dubbed “A Night to Remember,” the August 9 fundraiser, at $180 a plate, is to raise money to complete the lower level, or “educational floor” of Chabad of La Costa, which is located at 1980 La Costa Avenue. Plans include installing preschool classrooms, a teacher’s lounge, a larger library and a walk-in freezer.

“Channah came to Chabad about 13-14 years ago; she had recently lost her husband and was at odds with herself,” Lebovitz said. “We became very close, as widowed people do. We shared all our angst and intimacies. We devoted ourselves 100 percent to the shul and began doing all the special things for the shul. Because I was always in the kitchen, Channah became part of the kitchen crew – the kiddush crew – and they keep saying ‘Make the egg salad the way that Channah made the egg salad.’

“Channah was a first generation American from Maine,” Lebovitz added in tribute to the friend who will be her co-honoree at the fundraiser. “She used to say that she was from Anatevka and the rest of us were from America. She supported three congregations: one in Maine; Temple Solel, when Rabbi [David] Frank was there, and her heart was with Chabad, with Rabbi and Nehama. During COVID, she made sure there was money for the soup and challah Fridays, and she contributed money every month. To this day, money is being contributed by her trustee. She contributed anytime that anything occurred: her hand was in her pocket immediately. She died last August. Her first-year yahrzeit is coming up. The rabbi took her home to Maine to be buried.”

Looking ahead to the gala, Lebovitz told me, “The one thing in which I hold the greatest pride is that I have become the matriarch of this shul. I am so proud to have Yeruchem and Nehama as special parts of my world.”

*

Donald H. Harrison is editor emeritus of San Diego Jewish World. He may be contacted via donald.harrison@sdjewishworld.com