By Donald H. Harrison

SAN DIEGO — Now in its eighth year of existence, San Diego Generations of the Shoah is comprised of approximately 100 descendants of survivors of the Holocaust. Its two main missions, according to Sam Landau, who chairs the steering committee, are “remembering our parents and those relatives who were murdered in the Holocaust” and “providing funds to organizations that support Holocaust education.”

Landau, 75, said the group’s creation was prompted by the realization in 2016 that Holocaust survivors were dying at a rapid rate, and that after they were gone, their children were needed to retell their stories. “They went through so much and they have histories and stories.” Through the Generations of the Shoah group, “we are letting them know we remember you, we respect you, we appreciate you, and we don’t want your stories to die when you do.”

Children of Holocaust Survivors, known to each other as “the Second Generation,” decided to create a number of subgroups to accommodate different interests. One group works with a separate organization, The Butterfly Project, which was co-founded by Landau’s wife, Jan. The Butterfly Project memorializes the lives of 1.5 million children killed by the Nazis by painting and exhibiting throughout the world one ceramic butterfly for each of those children. “We’ve developed a speakers bureau so that people other than the Butterfly staff can come and tell their stories as well,” Landau said.

Other sub-group discuss books about the Holocaust, movies relating to the Shoah, and practice communicating in Yiddish. Another sub-group focuses on the question of “What do we do for the Third Generation? How do we get them to participate?” Landau told me during a recent interview.

Events bring together the general membership. Recently, there was a gathering they called their “Precious Legacy” at which members brought in various artifacts from their parents’ former lives. A reprise of that event is planned in December at the Rancho San Diego County Library, where an exhibit curated by Second Generation member Sandra Scheller focuses on the lives of survivors who immigrated to San Diego County. Scheller’s parents were Ruth and Kurt Sax of Chula Vista.

Another event sponsored by San Diego Generations of the Shoah is an annual summer picnic, which is a continuation of a tradition started by many of their parents as members of “The New Life Club.” That club, still in existence and recently brought under the auspices of the Jewish Federation of San Diego, has provided social opportunities for Holocaust Survivors since it began in 1953.

Children of Holocaust survivors swap tales about how they grew up, and how their parents’ experiences in the Holocaust impacted them. Without mentioning anyone by name, Landau said the experiences are quite varied. One member confided to their group about a mother who was verbally abusive. When that mother’s children made a mistake, or failed to live up to her expectations, “she really lashed out at them,” Landau said. “Sometimes, she wished that maybe she had died at Auschwitz, instead of having kids like them.”

Asked why a mother would behave like that, Landau, an organizational psychologist, commented, “I’m not a clinician, so I can’t go into the psyche, but I think it was just a form of frustration, a form of letting out fears. I don’t think there was physical harm. I don’t think she hit them.”

In contrast, said Landau, his own mother, Elka Fellner Landau, “was overprotective.” She followed the sha shtill philosophy of “not standing out, being more quiet, and staying in the background, based on her experiences,” Landau reflected. “I think as a child growing up, I was very timid. I remember in school knowing the answers to questions but not raising my hand. When I was called on, sometimes I got it right, sometimes I got it wrong, but that was what it took to get me to speak out. I think I was more focused on my mother. I reflect more of her characteristics than I do of my dad’s.”

His father, Max, who lived to the age of 104, “had always been very forward, vocal, and strong in voicing his opinions,” Landau said. “He didn’t shy from expressing himself.”

Both his parents came from Buczhaz, which was then part of Poland and today is part of Ukraine. They knew each other as children, but the war took them in different directions. Elka was one of 11 children in her family, only three of whom survived the Holocaust. Her parents, who had a bakery, and older siblings who had children of their own “all were murdered during the war.” Elka saved herself by fleeing to Russia, where she was put to work on a collective farm.

Max, who had been apprenticed to a printer before the war, escaped to a different part of Russia after his brother was shot to death in the street. Diminutive in stature, Max worked as a lumberjack, “chopping down trees in the wintertime,” Landau said. “He didn’t like that very much, so he went to a town near where he was working and there was a print shop there.” At first, there were no openings, but after one worker was fired for drunkenness, he was offered a job as a typesetter. He didn’t get to work there too long before he was drafted into the Russian Army, where “he worked on a newspaper for the generals, so he was away from the fighting.”

After World War II ended, Elka and Max returned separately to Buczacz, located about 84 miles southeast of Lviv. They were married shortly after their reunion and made their way to the Bindermichel Displaced Persons Camp in Linz, Austria, where Landau was born and lived until he was two years old. The family almost resettled in Israel, where Max’s brother had preceded them, but a visa from the United States changed their direction. Max told his son that “because of me, we got to San Diego. I was kvetching when we came through immigration.” Representatives of the American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee “felt sorry for me, this little kid, and they said, ‘Do you want to go to Chicago or San Diego?’ And he said, ‘What is San Diego?’ and they said, ‘It is nice and warm there.’ This was January 1950, and it was cold and miserable in New York, and he said, ‘Yes, I want to get out of the snow.’ So, they sent us here. We were very fortunate.”

“I didn’t speak English until I was 5 years old,” Landau recalled. “I went to a preschool, and I picked it up there. Kids wouldn’t understand what I was saying, but we got along playing, and so forth.”

Unlike some other immigrants, his parents were adept at languages. His father spoke Russian, Polish, Hebrew, Yiddish, German and English – remarkable considering that he only had a 6th grade education. In San Diego, Max set type by hand at the Arts & Crafts Press, which used to print phone books. Subsequently he was able to purchase Process Art Press, which was located downtown at 3rd and Market Streets, where he specialized in producing embossed letterheads, envelopes, social stationery, and wedding and bar mitzvah invitations. Elka meanwhile worked at a millinery shop.

They joined Beth Jacob Congregation, where Sam and Jan Landau still are members today. Sam’s only sibling, a sister who is an optometrist, lives in Half Moon Bay.

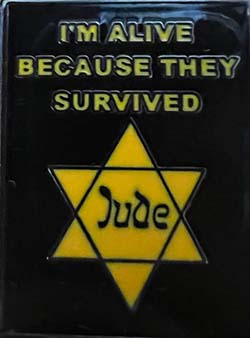

Perhaps everyone speculates on the quirks of fate that led to their parents meeting, being married, and having them as children. Add to that the incredible odds that Holocaust survivors overcame, and people like Landau voice appreciation and a sense of awe that they were born to such a couple and enabled to grow up in the United States. With this idea in mind, Scheller created a pin featuring a Jewish identification patch required by the Nazis that states, “I’m Alive Because They Survived.”

I wondered how Landau met his wife, Jan, and he told me, “She says it was a marriage ‘made in heaven.’ We met on an airplane. ‘Take a ride, come home a bride.’”

Jan, who grew up in Detroit, had been visiting relatives in Los Angeles, and was on a return flight to Michigan. Sam, a San Diegan who was studying psychology at Wayne State University, booked himself on the same flight from Los Angeles, rather from San Diego, because he wanted to experience a ride on a Boeing 747, which at that time had a piano bar on the second floor. They were seated in the same row with one seat between them. When a meal was served, it included a shrimp salad, which Sam didn’t eat because he kept kosher. So, he offered it to Jan, who grew up in an unorthodox home. They started talking, he moved over one seat to be closer, and after they arrived in Detroit, they stayed in touch. Landau often commuted the 45 miles between Wayne State University and the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor, where Jan was an undergraduate. When Jan came home to Detroit to visit with her family, they would go out on dates.

Landau said they were married about 2 ½ years after they met on the airplane. By that time, Jan had completed her undergraduate work and was teaching special education courses. After another two years, Landau completed his doctorate in psychology, and they moved to San Diego. Landau said his religiously observant Jewish parents had a profound impact on Jan, who became very involved with the Jewish community. She served as the principal of the San Carlos campus of the San Diego Jewish Academy before the school moved to a single location in Carmel Valley. Along with Cheryl Rattner Price, Jan also was a cofounder of The Butterfly Project.

The Landaus have four children, ranging in age from 31 to 45. Two of them – Aaron and Michael – are accountants in private industry and two others are Jewish communal workers. Daughter Naomi Shakhman heads the preschool at Soille San Diego Hebrew Day School. Eli is an accountant with the Jewish Community Foundation of San Diego. Naomi’s children, 18-year-old twins Ethan and Sari, having graduated high school, are planning to spend a year in Israel at seminaries for young men and women respectively.

I asked what important lessons from the Holocaust Landau’s parents had passed on to him, and what lessons he, in turn, passed onto his children.

He replied that his parents were “very proud of being in the United States, very happy, very patriotic, and I think some of those values were displayed to me. I feel very strongly about this country and the opportunities that are here and the freedoms that we have. It was so important to them, coming from an environment where they had no say in ruling their lives … It was really a land of milk and honey, a Garden of Eden, compared to what they had in the past.”

Talking to his own children, back when they were growing up, he emphasized how wonderful it is to live in a country where people have opportunities. “I tried to convey that they are lucky to be here for various reasons and emphasized the whole idea of gratitude and appreciation.”

Although Holocaust survivors had different kinds of experiences – some had fled to safety; others managed to live through the torture and deprivation of ghettos and concentration camps; others were hidden as children by Christian families, and still others fought as partisans – among the Second Generation, “there was a sense that we are family, that we are connected, that there was some commonality,” Landau said.

“My best friends, growing up, were children of survivors, mostly members of the New Life Club,” he added, “We went to different schools that were spread out across the county, but when we did get together at social outings, or parties, my best friends were from that group.”

When members of his age group were in their 40s and 50s, their parents encouraged them to create a formal social group for those of the Second Generation. At the time, working at their jobs, raising their families, members of the Second Generation didn’t have the time, or the interest, in sustaining such a group. Once they reached retirement age, however, and observing the resurgence of antisemitism around the world, they were more receptive to creating a Second-Generation group.

Now that Landau and others are septuagenarians, they wonder about their children and grandchildren. Will they too be motivated to keep the memory of the Holocaust alive?

*

Donald H. Harrison is editor emeritus of San Diego Jewish World. He may be contacted via donald.harrison@sdjewishworld.com