By Donald H. Harrison

SAN DIEGO – Descendants of two well-known Jewish graphic artists shared stories about their forebears during back-to-back panels Thursday, July 20, at the Comic-Con convention.

Karin Babbitt told a packed room that her mother, Dina Gottliebova Babbitt, volunteered to be transferred from the Theresienstadt model ghetto to Auschwitz in order to accompany her mother, Johanna, to the notorious death camp.

Assigned to a children’s barracks, Babbitt painted on a wall a scene from Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs, an animated film she had risked her life to see seven times prior to her incarceration by tearing from her clothing the Yellow Star that identified her as a Jew.

SS guards saw how beautifully Dina Babbitt painted and brought to her photographs of family members on which she modeled portraits. Her skill—especially being able to render skin tones very accurately—brought her to the attention of the camp’s sadistic doctor, Josef Mengele, who was known to the prisoners as “The Angel of Death” because he decided which arriving inmates should be permitted to work at the camp, and which should be sent immediately to the gas chambers. Mengele was also notorious for conducting cruel medical experiments on the prisoners.

Mengele ordered Dina to paint pictures of Roma and Sinti prisoners, who like the Jews were victims of the Nazi genocide. She successfully bargained with Mengele that she would do so if he would spare the life of her mother.

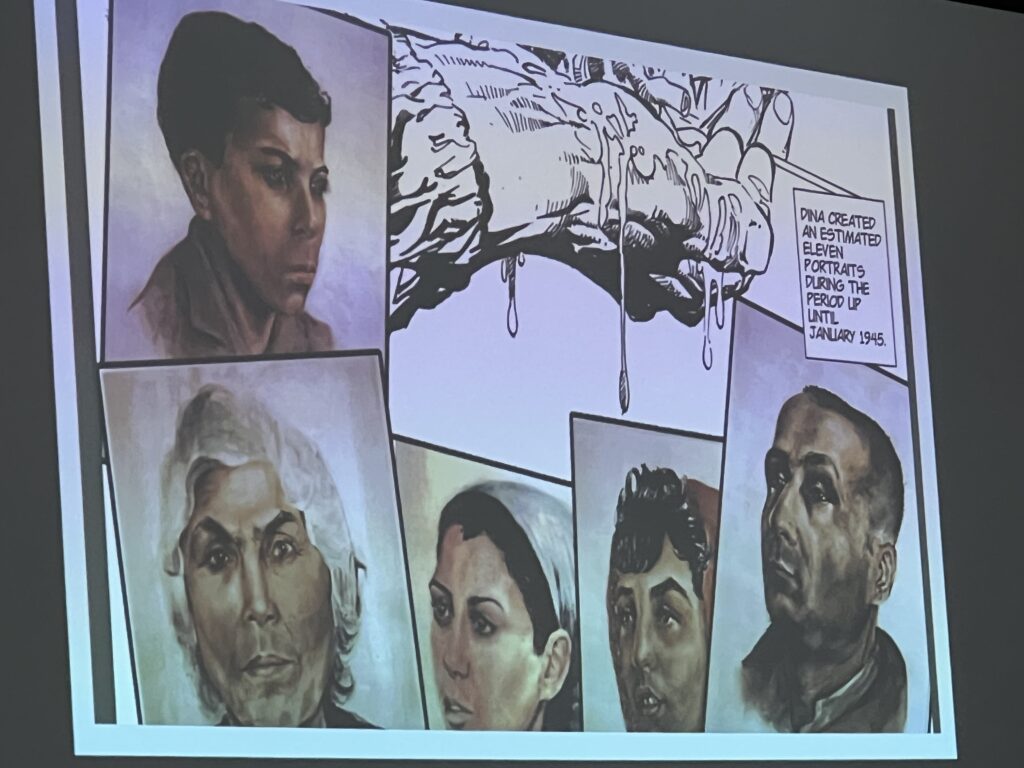

According to Karin, “Mengele sent her into the room and forced her to paint not only the Roma and the Sinti, but a lot of his experiments.” Karin showed a slide of some of her mother’s paintings, which the Auschwitz-Birkenau Museum had refused to deed over to Babbitt, despite a campaign that won the support of many members of Congress prior to her death in 2009.

The eyes of her subjects are anguished, which, according to Karin, was one way her mother tried to graphically portray the horrors of the Nazi genocide.

A French Roma woman named Selim, who was wearing a scarf, “had just given birth and the baby died because she was unable to provide milk,” Karin reported at Comic-Con. “My mother was painting her and taking a very long time because she knew when she was done painting, Selim would be murdered.”

While she was completing the portrait, “Mengele came into the room and was angry that she (Selim) looked so beautiful,” Karin related. “He grabs the scarf and he cuts it away from her ear, and he says ‘Show me the inferiority of the hairline! Make sure that you are recording the inferiority of the ear!”

After the war, Dina made her way to the United States, “broke, poor, and starving.” Seeking work, she went to an animation studio, with a fake portfolio, and was sent away by a receptionist. “She faints from malnutrition right at the desk,” Karin related. “An animator comes from inside, asks what is going on—a beautiful woman, passed out, this is cool – picks her up and carries her into his office. Two months later, Art Babbitt marries Dina Gottliebova and that is how my parents met.”

Art Babbitt was famous as the illustrator of the Disney character Goofy, and also drew the Wicked Witch in Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs. A scene that had Dina so fascinated that she had risked her life seven times to see in Czecheslovakia, of a feather being blown up into the air, was also one of his creations. “So, she married the person who drew her favorite scene.”

Karin Babbitt was a member of a 1:30 p.m. to 2:30 p.m. panel on the Art of the Holocaust that also included Ben Midler, a survivor of six concentration camps; aerospace engineer Edmundo Godinez, who was inspired to take up his old hobby of graphic art to produce scenes based on Midler’s life; Sandra Scheller, the curator of the Holocaust exhibit at the Rancho San Diego library that traces the lives of Holocaust survivors who settled in San Diego County, including Midler; and moderator Matt Dunford, chairman of San Diego Comic Fest. It was the sixth consecutive panel on the Holocaust that Scheller had organized since 2018 at Comic-Con.

Immediately prior to that panel, in the upstairs Meeting Room 4 of the San Diego Convention Center, a larger panel gathered to reminisce over the comic book creations of Jack Kirby (1917-1994), who was born as Jacob Kurtzburg and lived as a youth on New York’s Lower East Side, where he was a member of a street gang that defended its turf against other gangs.

One of Kirby’s drawings shown on screen was of a crowded street scene, where almost every inch of the composition was filled with people engaged in various activities of that neighborhood. There were so many little scenes within the composition that you could see something new in it every day.

Tracy Kirby, granddaughter of the legendary titan of the comic book world, recalled seeing that picture in the hallway between the kitchen and Jack Kirby’s home studio. “Even as I got older, there were so many pieces to look at, you would always find something different,” she said. “It wasn’t something that you got used to as you passed by. And, it would always be, ‘Oh, let me tell you this story about how I drew the picture of the guy with the cigarette up in the left-hand corner, and that would turn into another story and another story. So, these were really cool building blocks which helped create new visions for other stories somewhere else.”

The panel’s moderator, Rand Hoppe of the online Jack Kirby Museum and Research Center, asked Tracy whether the stories that her grandfather told stayed the same or changed. She responded that her grandfather would closely monitor reactions to his spoken stories, and he would “change the story based on how that person, as a kid, would react to it. Now, as I look back, yes, sometimes the stories changed, but it was to create a new story based on how we were reacting at the time, to make it even better.”

While Kirby was perhaps best known as the creator of numerous super heroes, among them Captain America, the Fantastic Four, the Hulk, Ant Man, Thor, Iron Man, Avengers, X-Men, and Black Panther, panelists decided to focus on the comics that he produced or supervised in other genres such as kid gangs, war stories, romance stories (even including divorce stories), animal stories, and crime stories.

Tracy commented that her grandfather benefitted from many sources of inspiration. “There was so much mythology. For Thor, Norse mythology was a big influence. There was Jewish mysticism and mythology. There were historical stories. We had a collection of National Geographics that was amazing. There were so many facets … we need to have another panel!”

Cartoonists Bruce Simon said some of Kirby’s kid-gang stories were influenced by his upbringing in New York City, and the war stories were gleaned from his experiences fighting his way through Europe during World War II. Cartoonist Mark Badger said “Jack’s work is highly, highly skilled. … What Jack did: he brought this incredible intelligence to drawing.” Tom Kraft of the Jack Kirby Museum & Research Center said Kirby often brought to his kid-gang stories similar characters: a wise guy, a brainy guy, a dopey guy and a rather good-looking guy. I think one was even called Good Looks.”

Sydney Heifer, a scholar of romance comics, admired some of Kirby’s plots, including one where a husband shares a home with identical twins, and becomes confused about who is who. Editor John Morrow said Kirby included a reference to his wife in one wartime story: he named a plane the Rosalind K.

There were also Kirby’s story titles that were a bit raunchy, some panelists agreed.

Piped up Tracy Kirby: “My grandfather didn’t tell me any of these stories.”

*

Donald H. Harrison is editor emeritus of San Diego Jewish World. He may be contacted via donald.harrison@sdjewishworld.com