By Donald H. Harrison and Emily Scalmanini

SAN DIEGO –The USNS Ruth Bader Ginsburg has not yet been built at the General Dynamics/ National Steel and Shipbuilding yards at 2798 East Harbor Drive. However, its construction has been approved by the U.S. Department of Defense as the eighth fleet replenishment oiler in a class of ships named for people who contributed greatly to the cause of equal rights for all. The ship is expected to be launched in 2026.

Ruth Bader Ginsburg (1933-2020) was an Associate Justice of the U.S. Supreme Court, known throughout her career for her belief that the U.S. Constitution demands that men and women be accorded equal rights.

During a hearing before the Senate Judiciary Committee, Ginsburg declared to Senator Edward Kennedy of Massachusetts, “I am alert to discrimination. I grew up during World War II in a Jewish family. I have memories as a child, even before the war, of being in a car with my parents and passing a place in [Pennsylvania], a resort with a sign out in front that read: ‘No dogs or Jews allowed.’ Signs of that kind existed in this country during my childhood. One couldn’t help but be sensitive to discrimination living as a Jew in America at the time of World War II.”

When built, the USNS Ruth Bader Ginsburg and others in its class of civilian-staffed ships will symbolize America’s ongoing commitment to the goals set in the preamble of the Constitution: “to form a more perfect Union, establish Justice, insure domestic Tranquility, provide for the Common Defense, promote the general Welfare, and secure the Blessings of Liberty to Ourselves and our Posterity.” All the ships were named for deceased individuals whose efforts were notable in advancing these causes.

The first such ship was named for the late Congressman John Lewis, D-Georgia, an African-American who had been a key figure in the U.S. Civil Rights Movement of the 1960s. All the replenishment oilers that follow are members of the John Lewis class of ships.

After the John Lewis, replenishment oilers were named for Harvey Milk, Earl Warren, Robert F. Kennedy, Lucy Stone, Sojourner Truth and Thurgood Marshall. Following construction of the USNS Ruth Bader Ginsburg, the next ship will be named for Harriet Tubman, according to the Defense Department.

Ships with a USNS designation are owned by the Navy but operated by the Military Sealift Command. That command utilizes U.S. Coast Guard-certified civilian employees of the Defense Department rather than U.S. Navy sailors. These ships carry no offensive weapons, except for pistols and rifles which crew members may use to defend themselves. On the other hand, ships with a USS designation have offensive weapons aboard and are crewed by trained military.

When Secretary of the Navy Carlos Del Toro announced on March 31, 2022 that the seventh of 15 John Lewis-class replenishment oilers would be named for Ginsburg, the Navy described the ships as being “designed to transfer fuel to the Navy’s operating carrier strike groups. The oilers have the ability to carry a load of 162,000 barrels of oil, maintain significant dry cargo capacity, aviation capability, and a speed of 20 knots.”

The Navy added that General Dynamics-National Steel and Shipbuilding Company designed the vessels with double hulls that protect against oil spills as well as strengthened cargo and ballast tanks. The 742-foot long ships, known to the Navy by the initials T-AO’s, with a full load displace 49,850 tons, according to the Navy. The Ruth Bader Ginsburg will carry the military identification of T-AO-12.

Columbia Law School Professor Jane Carol Ginsburg, daughter of the late Supreme Court Justice, was named as the ship’s sponsor. As such, she may participate in the ceremonial milestones of the ship including its keel laying, christening, and commissioning. According to the Navy, “Far beyond participation in ceremonial milestones, Sponsorship represents a lifelong relationship with the ship and her crew. While this bond begins with the ship’s christening and the initial (plank owner) crew, it will ideally extend throughout the ship’s service and even beyond. Sponsors are encouraged to make every effort to foster this special relationship, and to maintain contact with the initial and successive captains and the amazing men and women who comprise her crew. This can be as simple as exchanging e-mails or holiday greetings to participating in sail-aways and homecoming events.”

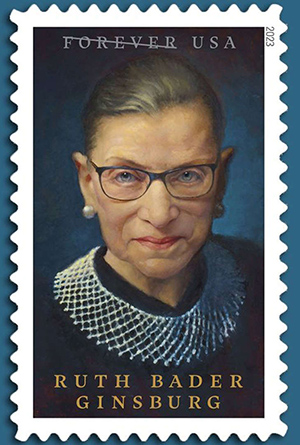

Jane Carol Ginsburg directs Columbia Law School’s Kernochan Center for Law, Media and the Arts. Asked what she would like the civilian crew who will serve aboard the Ruth Bader Ginsburg to know about her mother, she replied in an email that they “might peruse two of her books: My Own Words and Justice, Justice Thou Shall Seek. The latter title was taken from Deuteronomy 16:20: Tzedek, tsedek, tirdof. For a keepsake, or memento of her mother’s, she suggested the ship may wish to display the poster that accompanied the issuance in October 2023 of a U.S. Post Office stamp in Judge Ginsburg’s honor.

Jane Carol Ginsburg directs Columbia Law School’s Kernochan Center for Law, Media and the Arts. Asked what she would like the civilian crew who will serve aboard the Ruth Bader Ginsburg to know about her mother, she replied in an email that they “might peruse two of her books: My Own Words and Justice, Justice Thou Shall Seek. The latter title was taken from Deuteronomy 16:20: Tzedek, tsedek, tirdof. For a keepsake, or memento of her mother’s, she suggested the ship may wish to display the poster that accompanied the issuance in October 2023 of a U.S. Post Office stamp in Judge Ginsburg’s honor.

An article by Nancy Gertner in the Shalvi/ Hyman Encyclopedia of Jewish Women noted that Ruth Bader Ginsburg “was one of only nine women in a class of over five hundred.” She made law review at Harvard, later transferring to Columbia Law School, where she tied for first place in her class. Despite her obvious qualifications, Ginsburg received no job offers from New York’s law firms. In Joyce Antler’s 1997 book, The Journey Home, Jewish Women and the American Century, Ginsburg was quoted as saying, “In the Fifties, the traditional law firms were just beginning to turn around on hiring Jews. But to be a woman, a Jew and a mother to boot — that combination was a bit too much.”

Eventually, Ginsburg secured a job as an assistant professor at Rutgers University Law School, later moving on to offer the first course on women’s rights at Harvard Law School in 1971. She became the following year the first tenured female law professor at Columbia Law School. In 1972, she co-founded the Women’s Rights Project, where, according to Gertner, “her storied career as an advocate began.”

In a Sept. 20, 2020 article by Liz Mineo in The Harvard Gazette, Harvard Law Prof. Tomiko Brown-Nagin commented, “Well before she ascended to the Supreme Court, Ginsburg had left an indelible mark on law and society. At the ACLU Women’s Rights Project, she was the chief architect of a campaign against sex-role stereotyping in the law, arguing and winning five landmark Supreme Court cases during the 1970s. These decisions established the principle of equal treatment in the law for women as well as men and banished numerous laws that treated men and women differently based on archaic gender stereotypes. Her achievements as a litigator made her, as many have said, the Thurgood Marshall of the women’s rights movement.”

In 1971, she wrote the brief in Reed v. Reed by which she was instrumental in persuading the Supreme Court to extend the 14th Amendment’s equal protection clause to women. Incrementally, she continued to achieve victories establishing equality of men and women. In 1975, in Weinberger v. Wiesenfeld, she successfully argued that widowers should be entitled to the same survivor benefits provided to widows by the Social Security Administration. In 1979, in Duren v. Missouri, she successfully argued that jury duty should be a requirement for both men and women, not just men.

In 1980, Ginsburg was appointed by President Jimmy Carter to the U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit where she served with future Supreme Court colleague (and fellow opera fan) Antonin Scalia. In 1993, President Bill Clinton appointed her as an Associate Justice of the U.S. Supreme Court, succeeding Justice Byron White. Clinton later would remark in an interview with ABC News, “Her 27 years on the Court exceeded even my highest expectations when I appointed her. Her landmark opinions advancing gender equality, marriage equality, the rights of people with disabilities, the rights of immigrants, and so many more moved us closer to ‘a more perfect union.’”

Her appointment to the nation’s highest court was the sixth for a jurist of Jewish faith. Predecessors were Louis Brandeis, Benjamin Cardozo, Felix Frankfurter, Arthur Goldberg, and Abe Fortas. During Ginsburg’s tenure from 1993 to 2020, she was joined on the High Court by two other Jewish Justices: Stephen Breyer and Elena Kagan.

One of Ginsburg’s most famous decisions, written for the majority, came in United States v. Virginia in which the U.S. Supreme Court ruled as unconstitutional the policy restricting admission to the Virginia Military Institute to men. Another was her dissent in Lily Ledbetter v. The Good Year Tire & Rubber Co., Inc. in which the majority ruled that Ledbetter had protested pay disparities between male and female employees too late in her career. Ginsburg countered that “Small initial discrepancies may not be seen … particularly when the employee, trying to succeed in a nontraditional environment, is averse to making waves.” Author Nancy Gertner observed that “the message was heard by the Congress. In 2009, Congress passed the Lily Ledbetter Law” which stated that “the statute of limitation for filing an equal pay lawsuit reseats with each new paycheck affected by the original discriminatory act.”

In 2003, in an essay for the book I Am Jewish, edited by Judea and Ruth Pearl, in honor of the declaration by their son Daniel Pearl before he was beheaded by terrorists in Pakistan, Ginsburg wrote: “The command from Deuteronomy appears in artworks, in Hebrew letters, on three walls and a table in my chambers. ‘Zedek, Zedek tirdof,’ ‘Justice, justice shalt thou pursue,’ these art works proclaim; they are ever present reminders to me of what judges must do ‘that they may thrive.’ … I am a judge, born, raised and proud of being a Jew. The demand for justice runs through the entirety of Jewish history and Jewish tradition. I hope, in all the years I have the good fortune to serve on the bench of the Supreme Court of the United States, I will have the strength and courage to remain steadfast in the service of that demand.”

This is not to say that Ginsburg was enthralled with all Jewish practices. True to form, she protested that boys at her synagogue had the opportunity to become a bar mitzvah but that she, as a girl in that era before bat mitzvahs became common, had no such opportunity.

Phil Weiser, a reporter for the Forward recalled that Ginsburg had a “Sandy Koufax moment.” Like the Los Angeles Dodger pitcher who declined in 1965 to pitch on Yom Kippur, Ginsburg, although not religious, refused to sit with the High Court at a session scheduled for that Day of Atonement. “As a result,” wrote Weiser, “Chief Justice Rehnquist changed the schedule, and the Court has not sat on Yom Kippur since.”

*

Donald H. Harrison is editor emeritus of San Diego Jewish World. Emily Scalmanini, who is interning with this publication, is a graduating senior in history at the University of San Diego.