By Emily Scalmanini

SAN DIEGO — The late philanthropist Ben Weingart, a prominent businessman and a dedicated advocate for the betterment of Southern California, is remembered in San Diego through the Weingart City Heights Library, a cultural and educational hub that serves City Heights, one of the most culturally diverse neighborhoods in San Diego.

The library, one of the busiest in the county, stands as a testament to Weingart’s commitment to community development. Described as “fabulously wealthy,” and respected as a gracious, old-fashioned gentleman not without his quirks, Weingart had a passion for helping those less fortunate. He lived authentically, and never wavered from his commitment to improving the lives of various members of his communities. Thankfully, his impact and legacy live on today.

Weingart was born to Jewish parents in Kentucky in 1888 in what can only be described as humble beginnings. At four years old, after his father died tragically, he and his two younger brothers were left by his ailing mother at the Hebrew Orphans Asylum in Atlanta, Georgia. He was adopted at age six by a devout Christian Scientist mother, eventually converting to her religion himself.

After traveling the country through small towns as a young man selling magnifying eyeglasses with a grifter named Leiber, Weingart moved to Los Angeles in 1906. After stints delivering laundry, managing hotels, and successfully inventing several useful items including toilet roll holders, Weingart eventually built a fortune. He became a millionaire by his early twenties, owning over 200 hotels, including Consolidated Hotels Corporation which operated multiple properties on Skid Row.

His “baby,” however, was his founding of Lakewood, later to become a city near Long Beach, California. His partners were Louis Boyar and Mark Taper in the development that constructed 17,000 houses. The $8,535 homes were purchased mainly by former military service personnel utilizing low-interest loans. In 1951, Time magazine referred to Lakewood as “the biggest US housing project.”

Through these pursuits and countless more, Weingart amassed a fortune which he used to create a lifetime of philanthropy, dedicated to racial and ethnic justice. A self-proclaimed “anonymous orphan” remembered for his tendency to wear suits for multiple days in a row and dining daily on an afternoon meal of PB&J sandwiches, Weingart no doubt was impacted by his precarious beginnings.

Deeply concerned for society’s most vulnerable populations, he used his vulnerability as fuel to create lasting change. Intelligent, gracious, and wealthy, Weingart had no shortage of romantic relationships. He married in 1917, and he and his wife Stella established the still active Weingart Foundation in 1951.

After Stella’s death, he entered into a relationship with Laura Winston, a Christian-Scientist who Weingart met in 1959 when she was 34 and he was 71. When Weingart died in 1980, a 15-year controversy erupted between Laura Winston and Weingart’s business partners, who were conservators of his estate. Winston stated that she was “like a wife” to Weingart, and he once referred to her as “the most thoughtful girl I’ve ever known.”

“I used to remember telling people how close we were by saying, “Did you ever have a partner on the dance floor that you were so close – and I don’t mean physically – that there was no resistance when your partner stepped away? Well, Ben and I were like that in life,” Winston explained in an interview. “My business was to keep Ben healthy and happy. And I think I did a terrific job. Ben said he was happier with me than with anyone in his whole life.”

Weingart’s will originally intended to give Winston a monthly $2,000 for 15 years, an apartment, car, diamond ring, partial ownership of an apartment building, and $50,000 on top of that. Winston had argued in court that Weingart had wanted to give her even more, about $2 million, but this claim was denied by the conservators and she was evicted from their home. After a long fight, Winston won a private settlement in the “low seven figures” in 1988 according to the New York Times. The majority of Ben Weingart’s fortune was thus left to the Weingart Foundation.

The foundation continues to play a pivotal role in supporting numerous nonprofits and

initiatives aimed at addressing issues in education, healthcare, human services, and community development. The Weingart Foundation’s mission statements explain that the Foundation is dedicated to “racial, social, and economic justice for all,” helping “those who have historically been excluded due to their race, income level, gender, religion, immigration status, disability, age, sexual orientation, or zip code.”

It has disbursed more than $1 billion in grants and loans, benefiting a multitude of organizations throughout the Southern California region. A portion of these efforts went into the creation of libraries, recognizing the pivotal role they play in fostering education and community connectivity.

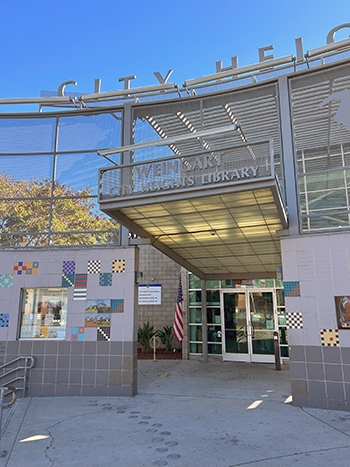

The Weingart Branch Library, named in honor of the philanthropist whose contributions were steered by Price Club founder Sol Price, opened its doors in 1998 as a vibrant community space designed to serve residents of all ages. As visitors stroll through the library’s doors, they’re not just stepping into a space of learning; they’re stepping into a community that’s tight-knit and thriving.

Nestled in the heart of City Heights, the library has become a vital resource for education, recreation, and community engagement. Branch Librarian Uyen Tran is clear on the library’s goals and impacts. “What I love about City Heights,” she explains, “is that they had such a great vision. The city wanted a new police department here in City Heights but they didn’t have the money. So, Mr. [Sol] Price, founder of Price Club and Price Philanthropies, said that he would donate and help build this area- but he got to do the urban planning. He decided this was going to be a walkable urban village center. It has to have a police department next to a retail center next to a park next to an elementary school next to a library. Very forward thinking. And the Weingart family donating to social causes to address inequality and racism- this is way before BLM (Black Lives Matter) and all these things. We should be proud of our name! These people were great at seeing the future and having a lasting impact. I can’t think of any other libraries that had that much foresight.”

The library isn’t just shelves and hushed whispers; it’s a dynamic space, serving around

12,000-13,000 folks each month. Before the COVID 19 pandemic, they were hitting around 20,000 visitors a month, reflecting just how much the library serves the community. “City Heights is a community of immigrants. A lot of our books are on citizenship, ESL learning, and foreign language collections – in every language we can get our hands on because we know that our community is so diverse.”

When asked about the library’s thoughts on nation-wide efforts of book banning, Tran explains, “I think it’s sad. Books are about literacy. We are trying to get people to read. That’s our priority. If anyone wants to complain about a book, great – you’re

reading!”

Although there is nothing in the library about Weingart with the exception of his name, the Weingart Branch Library reflects Ben Weingart’s commitment to providing accessible and enriching opportunities for learning, reflecting a pattern of his other projects. The library hosts various programs and events, from children’s story hours to adult education classes, creating a dynamic space for free and community-driven programs.

The library also hosts cultural events, such as that of Dia de Los Muertos [Day of the Dead] and Lunar New Year, as well as youth camps, educational programs, summer reading, music classes, and sustainability and gardening programs. “Because we know

there is a food desert here- families don’t have access to healthy and nutritional food, we want to create a space where kids can get introduced to different fruits and vegetables to connect with nature, learn and eat at the same time.”

As residents and visitors alike continue to enjoy the resources and opportunities provided by the Weingart Branch Library, Ben Weingart’s vision for a connected community thriving on racial amity remains a vibrant reality in the heart of San Diego.

*

Emily Scalmanini is a senior history major at the University of San Diego. This article was part of an internship with San Diego Jewish World‘s Editor Emeritus Donald H. Harrison.