Editor’s Note: This is the 19th chapter in Volume 3 of Publisher and Editor Donald H. Harrison’s 2022 trilogy, “Schlepping and Schmoozing Along the Interstate 5.” All three books as well as others written by Harrison may be purchased from Amazon.com.

Editor’s Note: This is the 19th chapter in Volume 3 of Publisher and Editor Donald H. Harrison’s 2022 trilogy, “Schlepping and Schmoozing Along the Interstate 5.” All three books as well as others written by Harrison may be purchased from Amazon.com.

Schlepping and Schmoozing Along the Interstate 5, Volume 3, Exit 47 (Palomar Airport Road): Polo/ Ralph Lauren Factory Store

From Northbound Interstate 5, take the Palomar Airport Road exit, turn right and then make a left onto Paseo del Norte. The Polo/ Ralph Lauren Factory Store is at 5600 Paseo Del Norte, Suite 100.

CARLSBAD, California — The Polo/ Ralph Lauren Factory Store is one of 85 stores at Carlsbad Premium Outlets, which showcases fashion designers, jewelers, perfumers, and other manufacturers who wish to take their products directly to the public. In San Diego County, other Ralph Lauren outlets are located in Alpine, La Jolla, and at the Las Americas Premium Outlets alongside the U.S.-Mexico border.

CARLSBAD, California — The Polo/ Ralph Lauren Factory Store is one of 85 stores at Carlsbad Premium Outlets, which showcases fashion designers, jewelers, perfumers, and other manufacturers who wish to take their products directly to the public. In San Diego County, other Ralph Lauren outlets are located in Alpine, La Jolla, and at the Las Americas Premium Outlets alongside the U.S.-Mexico border.

We take outlet stores for granted today, but back in the 1960s when Ralph Lauren still was getting started, department stores offering many varieties of goods were where most people shopped. The executives of these stores wielded lots of power. They could decide whose products would be shown and whose wouldn’t be, where and how they would be shown, and under what set of financial arrangements.

Lauren was one of the earliest designers to bolt the department store system, developing his own outlets rather than give into demands that his creations be marketed under a department store’s brand name or that he surrender his autonomy in designing and marketing clothing and accessories.

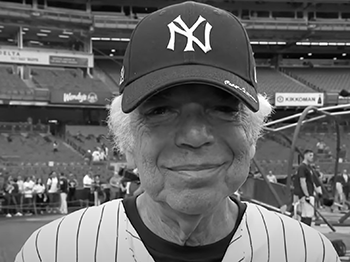

So, who is this fellow whose name is immediately identifiable with fashion? Articles too numerous to enumerate and many books have been written about him. If there is consensus, it is that when he was growing up as Ralph Lifschitz, the fourth child of Jewish immigrant parents he became enamored with the movies and the lives that they portrayed. Even as far back as middle school, he adopted the idea that “if you dress like them, you can be them,” which sounds like a variant of the popular expression, ‘fake it until you make it.”

Author Jane O’Connor, in Who is Ralph Lauren, published in 2017 for young readers, wrote, “For Ralph, seeing a movie wasn’t just about watching an exciting story unfold on a big screen. He could actually picture himself in the movie. He was John Wayne, riding off to catch the bad guys, wearing a cowboy hat, chaps, and dust-covered boots.”

Kathleen Baird-Murray, in the 2015 book Vogue on Ralph Lauren, noted that Lauren’s love of the movies was requited when his clothing was selected to dress Robert Redford as Jay Gatsby in the 1973 film, The Great Gatsby. Four years later, he supplied the eclectic clothes for Woody Allen and Diane Keaton in Annie Hall.

As a youth, Ralph became obsessed with fine clothing along with such other accoutrements of wealth as English sports cars. As a young man, he purchased a dark green Morgan sports car while still living with his parents. He could talk all day long about fashion and styles, but about other subjects he expressed very little interest. Although he made it through bar mitzvah and yeshiva, and later through DeWitt Clinton High School in the Bronx, academic subjects bored him. But talk to him about the cut of a jacket, or the width of a tie, and he would attend to the conversation with laser-like focus. Even sports did not hold that much interest for him; he liked to play basketball, but, according to former teammates, his idea of a winning game was when he looked stylish on the court.

Lauren enjoyed looking the part of a wealthy prep school graduate at an Ivy League college, or a member of the English nobility riding over his estate, or a sportsman engaged in a polo match, or a well-to-do rancher in the American southwest. Later on, he would design a range of outfits to go along with these imaginary environments — outfits and facades that other people wishing to project their own success were happy to buy into.

Warren Holstein, who was a teenager with Lauren, described him in an interview with Michael Gross, author of the 2003 biography: Genuine Authentic: The Real Life of Ralph Lauren. Holstein said that Lauren would often emulate “a certain character in a certain movie, a guy in an ad, a salesman we thought was cool. A chemistry teacher who buttoned his jacket in the wrong hole, and it was so cool. … He, out of whole cloth, had a vision of himself in the role of Prince Albert. He envisioned things and he stuck with them.”

These visions, in which he transformed himself from the son of working-class parents to the scion of old-money American families, were shared by the loyal clientele who rallied around the Polo/ Ralph Lauren brand. Author Jeffrey A. Trachtenberg in his 1988 biography Ralph Lauren: The Man Behind the Mystique, reported, “Many critics believe that his customers represent the worst in over-materialistic self-servers. To some, Ralph is symptomatic of a generation that values Hagen-Daz’s ice cream, designer jeans, and foreign sports cars more than marriage, kids, and good credit ratings. Ralph Lauren customers have always been pictured as insecure usurpers willing to pay almost any price to be accepted. Some see in these strivers an almost appalling lack of sensitivity to others, and consequently resent both the large salaries such customers earn and their self-indulgence. In turn, they resent Ralph Lauren.”

Initially, Lauren’s career consisted of a drab succession of jobs stocking shelves, or staffing a store counter, or selling products like ties to department stores. However, along the way, he learned the trade, and concluded that most stores were mired in the past, either unaware or uncaring that customers hungered for something different. He also understood that the more some consumers paid for a product, the more they valued it, however little it might have cost to produce it.

According to author Trachtenberg, Ralph followed the lead of his father Frank in changing his last name from Lifschitz. This was not only because of the scatological jokes that name evoked. His father wanted to be taken seriously as an artist and thought the name Frank Lauren would attract more interest and possible patronage for his art than the name Lifschitz. (I can relate. In 1909, my great-grandfather Velvel and grandfather Meyer changed our family name from Harowitz to Harrison, anticipating that to do so would assist my grandfather’s career as an architect.) On the other hand, author Gross reported that Frank’s name change was not official; it was an alias used for business only. Instead, it was Ralph’s older brother Jerry who initiated the name change for both of them. The brothers officially became Laurens in April 1959, a half year before Ralph’s 20th birthday on October 14th.

Ralph’s new moniker complemented the sense of fashion for which he was known all through high school and a truncated college career. What he may not have realized is that the Lifschitz name connected him to some of the most prestigious names in Ashkenazi Jewish history. According to the research of biographer Gross, these included Rabbi Lippman Heller of Prague; the Katzenellerbogen family of Padua, and such luminaries as Karl Marx, Helena Rubinstein, philosopher Moses Mendelssohn, composer Felix Mendelssohn, and England’s Montefiore and Salomon families.

While working as a salesman for A. Rivetz & Co., he won approval to design a line of ties. At that point, most men wore thin ties; Lauren decided to go in the opposite direction, choosing various materials for ties that were 3 1/2 inches wide. After he decided to market the ties on his own, executives at Bloomingdale’s wanted him to narrow the tie slightly and Lauren daringly refused. Although winning Bloomingdales’ account, in anyone else’s eyes, would have been a big victory, Lauren had larger ambitions to become himself a name brand. Lauren found other stores to sell the wide tie to, and as their popularity increased, Bloomingdale’s resistance correspondingly decreased. Whereas thin ties sold at the time for $5, Lauren’s ties commanded between $7.50 and $15. The more people paid for them, the more they valued them.

Wide ties required dress shirts with different collars, which in turn prompted the development of jackets, suits, and a whole line of menswear. The fact that Lauren named his brand “Polo” bespoke his desire to identify his clothing line with the wealthier classes — who else has the time or resources to ride perfectly groomed mounts around a field while attempting with a flexible mallet to knock a 3 1/5-inch diameter wooden or plastic ball into a goal? Eventually, Lauren would expand beyond men’s clothing into women’s fashion, fragrances, housewares, and other products. Not only was he conceptually the well-dressed actor in his mental movies, he also was the tasteful set designer. In Manhattan, he took over a four-story mansion to display his many product lines.

Lauren’s wife, the former Ricky Anne Low-Beer, like Ralph, was the child of immigrants. Also, like Ralph, she had remarkable Jewish yichus (lineage) — on her father’s side. The Loew-Beers, like the more famous Rothschilds, had been financiers in central Europe. Another branch were clothing manufacturers in Czechoslovakia. However, her mother was Catholic. Author Gross quoted a friend of Lauren’s from the early days of his marriage. “She’s half-shiksa,” the friend said. “He didn’t want his parents to know. He didn’t tell me why he didn’t. It was a compulsion, I think. He never talked politics, he never talked sports. Only taste. It was what he lived for. He liked her. He liked her looks … And they were all shiksa.”

Traditional Judaism holds that religion is passed down through the mother, in which case Lauren’s three children could not be considered Jewish. On the other hand, Reform Judaism says the children of a Jewish father are Jewish if they are brought up with his religion and profess no other. Ralph and Ricky’s sons Andrew and David both celebrated their bar mitzvahs after attending Hebrew school. Daughter Dylan did not have a bat mitzvah.

Lauren’s successful career made him a very wealthy man. He and Ricky purchased a 300-acre country estate in New York’s Westchester County; a two story Manhattan apartment; another home on the Montauk beach of Long Island; a ranch in Colorado; and a house in the Caribbean nation of Jamaica.

Lauren’s philanthropy has quietly assisted his old Bronx neighborhood’s institutions, including his public school and his synagogue. But he is better known for his support of cancer research. He cofounded the Nina Hyde Center for Breast Cancer Research in Washington D.C, and established a Ralph Lauren Center of Cancer Prevention and Care at North General Hospital in Harlem. He actively promoted cancer research fundraising through Fashion Targets Breast Cancer. He also created Pink Pony T-shirts, bearing a pink version of his polo pony logo. A portion of sales from each T-shirt is donated to cancer research.

Additionally, Lauren has supported literacy campaigns in New York. He donated $1.3 million for the restoration of the 30′ by 34′ flag that inspired Francis Scott Key in 1814 to compose “The Star Spangled Banner” — a job that author O’Connor reported took eight years because “every stitch in the flag had to be repaired.”

Lauren’s oldest son, Andrew (born 1969) has produced such movies as The Spectacular Now; High Life; Vox Lux; Anything’s Possible; The Squid and the Whale; The Brutalist; G; Light Years; Life 2.0; Mateo; and This Is Not a Robbery.

The younger son, David (born 1971), followed his father into the fashion design business as Polo/ Ralph Lauren’s vice chairman and chief innovation officer. He is married to Lauren Bush (who goes by Lauren Bush-Lauren), a model, fashion designer, and the granddaughter of the 41st U.S. President George H. W. Bush and niece of the 43d U.S. President George W. Bush. Lauren Bush-Lauren started FEED Projects in 2007, a fashion business that donates school meals to children in the U.S. and abroad with every product sold.

Ralph and Ricky’s daughter Dylan (born 1974) owns in Manhattan the 15,000 square foot Dylan’s Candy Bar, which promotes itself as the “largest candy store in the world.” She travels around the world to find unusual candies and by 2020, according to an article in the azureazure, was able to offer more than 7,000 varieties at her store. She is the author of the 2010 memoir Dylan’s Candy Bar: Unwrap Your Sweet Life.

*

Donald H. Harrison is publisher and editor of San Diego Jewish World. He may be contacted via sdheritage@cox.net