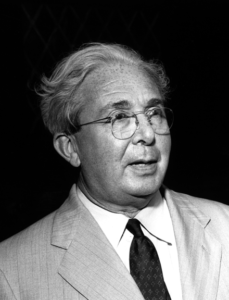

Leo Szilard (Feb. 11, 1898–May 30, 1964) was born in Budapest as Leo Spitz to civil engineer Lajos Spitz and his wife Tekla Vidor. In 1900, the family changed its name to Szilard, a Hungarian word for “Solid.” Although Jewish, he attended a Lutheran school along with such others as Edward Teller. After being sent to officer school by the Austro-Hungarian Army’s 4th Mountain Artillery regiment, he came down with the Spanish Flu and was discharged in November 1918 after the Armistice. Denied an opportunity to enroll at the Budapest University of Technology because of his Jewish ancestry, Szilard immigrated to Berlin, where he enrolled at Friedrich Wilhelm University, attending lectures by such luminaries as Albert Einstein and Max Planck.

Leo Szilard (Feb. 11, 1898–May 30, 1964) was born in Budapest as Leo Spitz to civil engineer Lajos Spitz and his wife Tekla Vidor. In 1900, the family changed its name to Szilard, a Hungarian word for “Solid.” Although Jewish, he attended a Lutheran school along with such others as Edward Teller. After being sent to officer school by the Austro-Hungarian Army’s 4th Mountain Artillery regiment, he came down with the Spanish Flu and was discharged in November 1918 after the Armistice. Denied an opportunity to enroll at the Budapest University of Technology because of his Jewish ancestry, Szilard immigrated to Berlin, where he enrolled at Friedrich Wilhelm University, attending lectures by such luminaries as Albert Einstein and Max Planck.

Szilard’s dissertation on a physics puzzle known as “Maxwell’s Demon,” involving the exchange of gaseous molecules between two different rooms, won top honors in 1922. Thereafter Szilard was appointed an assistant in to Max von Laue at Germany’s Institute of Theoretic Physics. He applied for patents for a linear accelerator, a cyclotron, and an electron microscope, and worked with Einstein on a refrigerator that had no moving parts. In 1933, after Hitler’s ascension as chancellor, Szilard moved to London. There, he obtained a patent for a neutron-induced nuclear chain reaction, which was assigned to the British Admiralty to ensure its secrecy. With Thomas Chalmers, a physicist, he developed a method for the preparation of medical isotopes. In 1938, Szilard moved to the United States, where he worked at Columbia University to demonstrate the concept of nuclear fission. He drafted a letter to President Franklin D. Roosevelt, which he got his more famous mentor, Albert Einstein, to sign warning of Germany’s nuclear weapons project. This eventually prompted the creation of the Manhattan Project at the University of Chicago. Szilard became a U.S. citizen in 1943.

The physicist foresaw what terror atomic weapons could unleash on the world and argued that they be demonstrated to enemies in the hope that they would surrender, rather than face annihilation. However, the decision was made to drop bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Szilard later turned his attention to the fields of molecular biology and short story writing.

In 1951, he married Trude Weiss, a physician whom he had known since 1929. In 1964, he became a resident fellow of the Salk Institute for Biological Studies in La Jolla but died of a heart attack that same year. His papers were donated to the library at the University of California San Diego.

Tomorrow, Feb. 12: Judy Blume

*

SDJW condensation of a Wikipedia article

A brilliant scientist (and humanitarian) – glad to see this bio.

Not included was that he was one of the major proponents trying to convince President Truman to drop the first Atomic Bomb offshore (to Japan) to demonstrate its destructive power.

The Wikipedia page on Leo is much more comprehensive

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Leo_Szilard

He never received a Nobel Prize.

A “lifetime achievement award for Service to Humanity” would have been totally appropriate.

His wife; Gertrude (Trude) Weiss – Szilard [Austrian-American physician and civil servant] had an illustrious career as well, and spent her later years in San Diego gathering Leo’s papers.

https://www.wikidata.org/wiki/Q52149296

She was a pediatrician colleague of my father’s in Vienna, and I had the privilege (while in high school in Chicago) of spending a Sunday Afternoon with my parents and them at their apartment in Chicago (totally clueless other than that they were “friends of my parents” from Vienna).

Thanks for the excellent article paying homage to Leo Szilard, one of the greatest Jewish scientists of the 20th

century. I had the privilege of knowing his wife, Trude Szilard, a brilliant woman in her own right.