By Alex Gordon, Ph.D

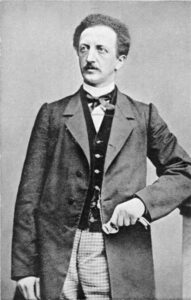

HAIFA, Israel – It is not known what the revolutionary movement and nascent socialism would have looked like had it not been for the unfortunate love affair of this man, hated by his famous rival for leadership in the labor movement, Karl Marx. On August 31, 1864, Ferdinand Lassalle, the German philosopher, jurist, and politician, died in Geneva at the age of 39 from wounds sustained in a duel.

Lassalle was a “wunderkind” of the socialist movement. At the age of 23, during the revolution of 1848, he was already a prominent figure in the radical Democratic Party in Prussia. As an employee of the radical New Rhine Gazette, whose editors were Marx and Engels, he claimed to be a follower of their ideas. Lassalle defied the authorities by “challenging them to a duel” with his vivid sociopolitical agitation. His fame was aided by the charge of high treason for this activity. He was arrested, the jury acquitted him, but the correctional police court sentenced him to six months’ imprisonment. In 1858 he became known as a philosopher by publishing a work on the ancient Greek philosopher Heraclitus. Three years later he became famous as a jurist through the publication of a major work, The System of Acquired Rights (1861). In 1863 Lassalle founded the workers’ union, from which today’s Social Democratic Party of Germany grew.

Karl Marx saw Lassalle as a powerful competitor and disliked him, although he accepted occasional monetary help from him. Lassalle was a Polish Jew. Marx considered Polish Jews “the dirtiest race,” probably because they were more observant than other Jews of Judaism and engaged in petty trade. Marx went as far as racism in his hatred of Lassalle: “That Jewish Negro Lassalle! Empty-faced and chest-thumping idealist! It is now quite clear to me (and the shape of his head and his hair prove it) that his ancestors were Negroes! Only the combination of Jewishness and Germanness with a primordially Negro substance could produce such a strange subject!”

Ferdinand Lassalle was born in Breslau on April 11, 1825. He was the son of a Jewish silk and weaving merchant. As a child he went with his father to a Reform synagogue and found prayers and rituals boring and meaningless. At home they observed traditional food and Sabbath rules and celebrated the holidays, but after the Sabbath meal they sat down to play cards, and during the Passover ceremony they read the account of the Exodus of the Jews from Egypt in excerpts to get down to eating as quickly as possible. Lassalle wrote in his diary on February 2, 1840, that although he did not keep the commandments, “I consider myself one of the best Jews in the world.” He wrote that his dream was “to be at the head of the Jews with arms in hand and lead them to independence.” Three days after this entry came the news of the bloodbath in Damascus.

During the Damascus trial of the Jews, a radical change occurred in Lassalle’s views. He lashed out at his people: “Despicable people, you deserve your fate. The worm caught under your feet tries to twist itself, and you only grovel more. You do not know how to die, to destroy, you do not know what fair vengeance means, you cannot die with your enemy, strike him down by dying. You were born to slavery.” Lassalle felt no solidarity with the Jews of Syria and began to distance himself from Jewry. He decided to become the “messiah” of the working people and break with the Jewish people. He wrote: “I do not like the Jews at all, I even despise them.” When Lassalle decided to break with Jewry, he wrote to his mother, who was observing the commandments of Judaism, that Jewry was “the most perfect ugliness.” He expressed his “messianic” aspirations in his diary on August 25, 1840: “I want to stand before the German people and before all nations with a fervent appeal to fight for freedom.”

Lassalle’s “narrow,” tribal ideal of the liberation of the Jewish people is replaced by the “great” ideal of the liberation of mankind. He believed that the struggle for workers’ liberation was an advanced and important cause, while the equalization of German Jews was a hopeless undertaking because of the inherent vices of the people. He decided that fighting for “universal” values would remove his duality as a Jew and a German and make him a leader of the workers. Apparently, Ferdinand Lassalle was one of the first self-hating Jews in history, as described in the Jewish German philosopher Theodor Lessing’s book Jewish Self-Hatred (1930). He was not only a follower of Marx in the struggle for the good of the proletariat, but also his disciple in the theory of Jewish antisemitism expressed in Marx’s article “To the Jewish Question,” where the author’s Jewish self-hatred is especially embodied in the remark, “The emancipation of Jewry is the emancipation of humanity from Jewry.”

Lassalle considered the state a lesser evil than the liberal party of the “exploiting class.” He did not like the Prussian regime, but he was in favor of a strong state power, not Bismarck’s regime, but Lassalle’s socialist regime. On the basis of his struggle against the common enemy, the liberals, Lassalle became close to Chancellor Otto Bismarck. They had secret meetings which came to light many years later, after Lassalle’s death. Bismarck, who defended the interests of the aristocrats and the military, hated liberals more than socialists. Bismarck saw the middle class, which carried the values of democracy and liberalism, as more serious opponents than the socialists, who, like him, were supporters of “etatism,” that is, of a powerful state.

At one point Lassalle made a move that drew serious criticism from Marx. He offered Bismarck the support of the workers in exchange for the introduction of universal suffrage, which Marx called a “petty-bourgeois utopia.” Lassalle allowed for the idea, impossible for Marxism, that workers could come to power not by revolution but by winning democratic elections. In 1867, already after Lassalle’s death, Bismarck introduced universal suffrage and labor laws, which, however, he repealed in 1878 after the defeat of the liberals. Lassalle was not an agent of Bismarck, as Marx and Engels mistakenly believed, but for a time an ideological affinity arose between him and Bismarck.

Toward the end of his life, Lassalle began to move away from his radical views and, to the displeasure of Marx and Engels, turned from a revolutionary to a reformist. He created the first trade union movement. At the end of World War I, the right wing of German Social Democracy, justifying its national patriotism and rejection of revolution, proclaimed the famous slogan “Back to Lassalle!” As a result, Lassalle’s ideas gradually displaced Marx’s ideas and made their author one of the ideologues of the right wing of German Social Democracy and the ideological platform of the modern German Social Democratic Party.

In his diary, Lassalle expresses an ardent love for Heine: “I love him, Heine. He is my second self. I love his bold ideas and the power of his language, which destroys everything! […] All the senses obey him, his irony amazes and destroys.” The two Jews, Heine and Lassalle, first met in November 1845 in Paris, where Ferdinand was going to collect material for his doctoral dissertation on the works of Heraclitus. The poet admired the young Lassalle: “No young man – he is 19 years old – has ever made such a strong impression on me with his knowledge and his personality. I am particularly struck by the strength of his intellect and the energy that dreamers like me lack.” Lassalle thought of joining Heine’s struggle with the poet’s relatives. Heine presented the case as “a struggle of genius against a purse of money,” but he framed it as “a struggle for the principle of creative freedom and the independence of the poet.”

When Ferdinand returned to Germany, Heine wrote to him in biblical terms: “The hearts of the moneyed pharaohs are so strong that it is not enough to threaten them, it is necessary to give them ten Egyptian executions. […] If Moses had said nice things, used half-hearted threats and logical arguments, the people of Israel would still be in Egypt.” However, when Heine perceived Lassalle’s calls for militant speeches and revolutionary plans, the poet became wary of this destroyer. He wrote to Lassalle’s father Heimann: “Poor Ferdinand Lassalle! My heart breaks at the sight of such a talent falling prey to demonic self-destruction.”

Heine felt disappointed by Lassalle’s actions. The differences between them began when Lassalle began to appear in German courts in defense of Countess Sophia von Hatzfeld in her divorce case. He began to help the Countess, whose husband had abandoned her, taken her children from her and left her destitute. It was the story he was looking for: a small human drama with great social meaning. A twenty-one-year-old Jewish young man with little legal training, connections, or influence entered into a struggle with a powerful count. In countless articles, at rallies and before judges, he argued that it was not a simple family quarrel, but “an example of the flagrant violation of the civil rights of women in the bourgeois-aristocratic environment,” “savage abuses of power and capital directed against the weak,” “the baseness of the ruling class.” He began a noisy campaign that lasted eight years (1846 -1854) in the courts and in the pages of the press.” The process ended in 1854 with the Countess’s victory: divorce and division of property in her favor. Sophia became Lassalle’s girlfriend. During the process, there was a crisis in the relationship between Lassalle and Heine. As part of the campaign he waged against the Countess’s husband, Lassalle asked for the poet’s help as a famous journalist. Heine did not agree to participate in this struggle. With his characteristic revelation, the poet criticized Lassalle’s activities. He scornfully rejected his request for help, calling the story a topic “belonging to the novels of Eugène Sue.”

In 1864, while in Switzerland, Lassalle, thirty-nine years old, fell in love with and proposed to the sixteen-year-old Helene, a Catholic, daughter of the Bavarian diplomat von Denniges. For the sake of this marriage he was even ready to convert to Christianity. But when he learned of Lassalle’s revolutionary views and Jewish background, the diplomat forbade the marriage. He wished his daughter to marry a Wallachian nobleman. Ferdinand challenged the groom to a duel, in which he was wounded and died of his wounds a few days later in Geneva. Lassalle was buried in the Jewish cemetery in Breslau. In life he cut himself off from the Jews. However, no matter what he did or how he behaved, his many enemies constantly perceived his deeds through the prism of his Jewishness. Thanks to Jewish religious customs, after nearly a quarter of a century of separation from his people, Lassalle was returned to them posthumously.

*

Alex Gordon is a native of Kiev, Ukraine, and graduate of the Kiev State University and Haifa Technion (Doctor of Science, 1984). Immigrated to Israel in 1979. Full Professor (Emeritus) of Physics in the Faculty of Natural Sciences at the University of Haifa and at Oranim, the Academic College of Education.