By Alex Gordon

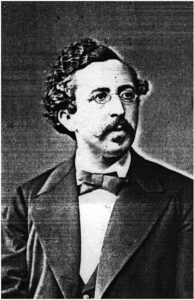

HAIFA, Israel –The German philosopher and religious Jew Hermann Cohen (1842-1918), was the only full professor of philosophy in Germany to receive this title without baptism. He was one of the founders of Neo-Kantianism and believed that Judaism was the first religion that could be qualified as a “religion of reason.”

The philosopher’s father was a cantor and teacher of religious subjects. Cohen received his traditional Jewish education at home while attending the city’s grammar school. He was a student at the Jewish Theological Seminary in Breslau, but gave up his intention of becoming a rabbi. Cohen studied philosophy at the universities of Breslau, Berlin, and Halle. From 1876 to 1912 he was professor at the University of Marburg, and from 1912 he was professor at the College of Jewish Studies in Berlin.

Cohen was an ethical socialist, calling Marx the messenger of God in history, but rejecting historical materialism and atheistic tendencies in the labor movement. He emphasized the spiritual affinity of Judaism with the teachings of Kant. His conclusion is a stretch. In claiming this affinity, the philosopher mixes the ideas inherent in Judaism with his own views. Judaism views man as “an accomplice in creation.” According to Cohen, man’s task is the creation of a united humanity, that is, the realization of a messianic kingdom, presented in terms of philosophical socialism as a struggle for justice and the rights of the poor. The coming of the messianic kingdom must be preceded by the creation of communities living in peace and harmony, which will serve as a model for humanity. The Jewish people, according to Cohen, constitute such a community.

The philosopher eclectically sought to reconcile the idea of Israel’s chosenness with the idea of humanity’s unity. Israel was chosen and dispersed among the nations in order to become the embodiment and symbol of humanity’s unity in history and thus to establish the kingdom of God on earth. Cohen’s messianism is secular rather than religious. His views are similar to those of Marx and Lassalle, spokesmen for a secular and often antireligious “messianism.”

Beginning with the Kant and Moses Mendelssohn dispute, the German-speaking world debated the question of whether Judaism was a religion of reason. Cohen believed that Germany was the only country in which reason and religious feeling could easily be combined because of its philosophical idealism. After the publication in 1879 of the historian von Treitschke’s article “On Our Jewishness,” a discussion ensued between Cohen and the author of the article. In polemicizing the historian’s anti-Jewish statements, Cohen preached a complete fusion of German Jewry with German society, “without any double loyalty.” Treitschke, however, thought: “Our demand of our fellow Jews is simple and elementary: let them become Germans, simply and truly feel German without distorting their old and sacred memories and the faith respected by us all. We do not want the millennial German culture to be replaced by an era of mixed Jewish-German culture.” The historian thought that full assimilation would be impossible: “The Jews will always remain as Oriental people who only speak German.” Von Treitschke considered Judaism an irrational religion, backward and preventing Jews from accepting German society. Cohen rejected Zionism as a betrayal of the Messianic ideal. The philosopher imagined the Jews as part of the Germanic world, attributing to them a Germanophonie “since all the basic potencies of mind and thought are shaped by language.” He wrote of a “profound fraternity between Judaism and Germanism.”

Cohen ignored what Oswald Spengler wrote about the Jews during World War I: “Even when [the Jew] considers himself part of the people of the country where he lives and shares its fate, as happened in 1914 in most countries, he does not actually experience this event as his fate, but he enters into a struggle for it, views it as an interested observer, and for this very reason the deep meaning of what is being fought over remains unavailable to him.” Spengler was putting aside the Jews who are raring to fight for the good of other nations. The “deep fraternity between Judaism and Germanism” of which Cohen wrote soon turned out to be a bottomless alienation and boundless hatred of the German nationalists toward the Jewish patriots of Germany.

World War I infected many German Jews with German nationalism. Cohen, who was caught up in the war in Berlin, believed that “in this patriotic war the highest ideals would be realized” and that it would bring Germany “heroic victory” over her malignant enemies. The harmonious coexistence of Germans and Jews is the conclusion of Cohen’s insight into the characteristics of both peoples. Cohen reached his conclusion about the idyll of Germans and Jews living together during a fierce discussion with von Treitschke, who called the Jews “our misfortune.”

Cohen declared that to serve Germany was a holy cause, “like serving God.” The philosopher dismissed the conflict between German culture and Jewish cosmopolitanism as ignorant absurdity. The tragedy of the philosopher’s position is particularly felt in his conclusion about the unity between the German and Jewish peoples: “We live by the high feelings of German patriotism, by the conviction that the unity between Germanism and Jewry, for which the whole history of German Jewry has paved the way, will eventually shine as cultural historical truth in German politics and in the life of the German people and even in the spirit of the German people.” Eighteen years after these lines were written, the “cultural historical truth” according to which Jews had no place in the Third Empire of the German nation became prevalent under Nazism.

In 1915, in the midst of World War I, the philosopher wrote his article “Deutschtum und Judentum” (Germanness and Judaism). Paraphrasing the title of Kant’s book on “pure reason”, we can classify Cohen’s work as a work of “pure madness.” His Germanic patriotism was mega-patriotism: “So, as Jews we too are proud to be Germans in this epic age in which the fate of nations is at stake, because we have realized that we must convince our fellow Jews throughout the world of the religious significance of Germanism, of its influence on the legal rights of Jews among the nations of the world both for their religious development and for all their cultural activity. In this way we feel as German Jews conscious of the central cultural force that calls to bring the people of the world together in consciousness of messianic humanity, and we can reject the reproach made against us [as Jews] that our historical nature corrupts the nations and tribes of the world. When again a serious effort at international reconciliation and a real, well-grounded peace is made, our example may properly serve as a model for the recognition of Germanic domination.” The philosopher’s words about “recognizing German supremacy” sound particularly frightening given the Nazis’ rise to power in Germany 18 years after these lines were written.

The progressive role of the German army in the liberation of humanity and the Jewish people, as expressed by Cohen, seems grotesque: “We also hope for a triumph of the German armed forces which will give human dignity to men. […] For ourselves, too, we hope above all to achieve the further establishment of full equality for our community along with the other religious communities of the German state […] and that the moral and religious equality of our religion will find unconditional recognition, that on the basis of this free step, this enlightenment our religious community will be linked to the Christian confessions in which our particular character still forms an indispensable basis for the ethical development of monotheism, which will finally open the gates universally.”

Contrary to Cohen’s hopes, no equality or recognition of Jewish religion was brought about by the Second German Empire. He had already been a professor at the university in Marburg for three years when in 1879 Wilhelm Marr’s first work of new, racial antisemitism, The Victory of Jewry over Germanism, viewed from a non-religious perspective was published, or rather was cast into the darkness. From that moment until the publication of the philosopher’s optimistic utopia Germanism and Judaism, 36 years passed. The number of works of racial Judophobia grew, supplanting religious Judophobia. The philosopher had enough time and material to recognize the change in Judophobic fashion: religion was receding into the past, condemnation of blood was taking its place, but Cohen continued to dream of a rapprochement of Jewish religion with Christian denominations. He argued that Judaism and Christianity would in the future merge into one, comprehensive, universal faith. In his terms, a “connubium” (Latin for legal marriage, a term from Roman law) between Judaism and Christianity, into a common “religion of reason,” would be easier in Germany than anywhere else in Europe.

Like Moses Mendelssohn, Cohen was against baptism, which he called a “religious false oath.” Like Mendelssohn, Cohen unintentionally generated the idea of the dissolution of the Jews into Christianity and German society, which pushed them out even during the “liberation,” World War I, which threatened both peoples equally, but which did not bring them closer together, but perhaps alienated them. The desire to be normal, like everyone else, produced an anomaly. The acute Jewish desire for emancipation seemed to be overblown, hysterical and unnatural.

Hermann Cohen died on April 4, 1918. The second empire of the German nation still existed, but the “victorious” war had already been lost. Contrary to Cohen’s expectations, the German armed forces had not given people human dignity. The philosopher had time to learn that “German supremacy” remained his unfulfilled dream, and that “full equality” for the Jewish community with other religious communities in Germany had not been achieved.

Today, the building of the philosopher’s last workplace, where he created the utopia Germanism and Judaism, is located in Berlin, at number 9 on the street named after the Jewish writer Kurt Tucholsky. Since 1999, the university building in which Cohen wrote his utopian work on German-Jewish unity has been called the Leo Baeck Building and is the seat of the Central Council of Jews in Germany. Europe, in the form of Sweden, did not recognize Tucholsky, who had fled Germany to Sweden, as its citizen. Desperate to be accepted by Europe, Tucholsky committed suicide in 1935. Hermann Cohen died his own death, but tried to live someone else’s spiritual life, in which he could find no place for himself or his people.

*

Alex Gordon is a native of Kiev, Ukraine, and graduate of the Kiev State University and Haifa Technion (Doctor of Science, 1984). Immigrated to Israel in 1979. Full Professor (Emeritus) of Physics in the Faculty of Natural Sciences at the University of Haifa and at Oranim, the Academic College of Education.