By Jerry Klinger

LONDON, England — A recent trip here gave me one day to wander. The Charles Dickens Home and Museum, where I believed I had an antisemitic bone to pick, was on the top of my menu.

The Charles Dickens Home and Museum, at 48 Doughty Street, is where Dickens wrote Oliver Twist, perhaps his greatest novel, 1837-1839. I knew of the antisemitic controversy surrounding Dickens.

The word “Jew” appears in Oliver Twist, 326 times. The name “Fagin” appears 306 times, almost always linked to the word Jew. The linkage was intentional.

Fagin means to criminally corrupt children. Unless Dickens linked Fagin to the word Jew, Fagin would have been another criminal product of London’s underclass.

Dickens needed something more his readers could readily understand. Fagin became the Jew.

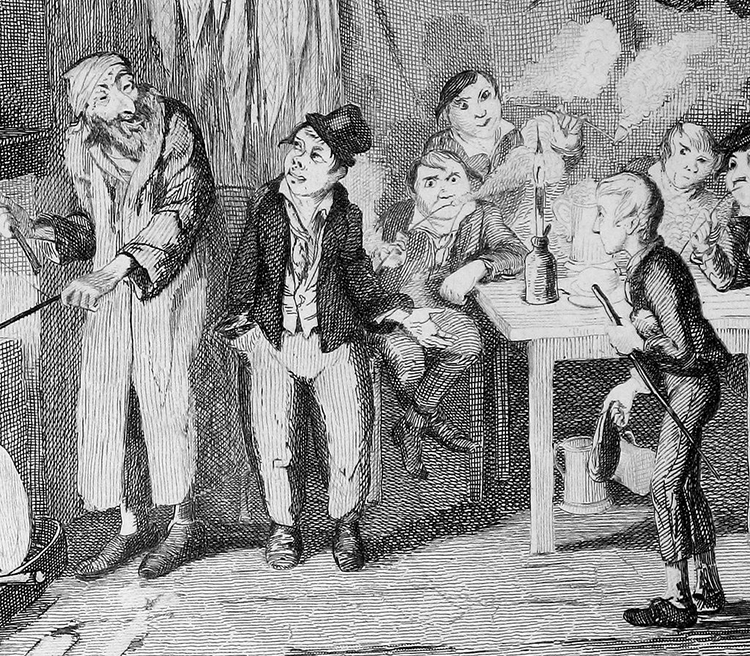

“He (Jack Dawkins – the Artful Dodger) threw open the door of a back-room and drew Oliver in after him….

In a frying-pan, which was on the fire, and which was secured to the mantelshelf by a string, some sausages were cooking; and standing over them, with a toasting-fork in his hand, was a very old, shriveled Jew, whose villainous-looking and repulsive face was obscured by a quantity of matted red hair….

…’This is him, Fagin,’ said Jack Dawkins; ‘my friend Oliver Twist.’ …

Bill Sikes, the murderer in the novel, was a violent, criminal drunk, – a man of absolute evil. Sikes is named 352 times. Never once was he branded as a Protestant or a Catholic.

Victorian English readers automatically understood the word “Jew” antisemitically, as malicious, malevolent, greedy, and corrupt.

Antisemitism has long been a part of British popular culture. Post-Holocaust it had been significantly frowned upon. Contemporaneously, post October 7, antisemitism has viciously reemerged with another adjective for Jew – Zionist.

Going to Dickens’ home, confronting the docents was an opportunity to lash ropes to his virtuous statue and perhaps metaphorically pull it down a bit in righteous indignity. Americans have a lot of experience doing that with our 18th and 19th century icons viewed through our 21st century dark pink sunglasses.

There never were any Jews at 48 Doughty Street in London. The only Jew at 48 Doughty Street was the villainous Dickens’ imaginary character.

When Dickens wrote Oliver Twist, he had never known a Jew. He based Fagin upon a notorious Jewish “thief and fence” he read about in the Times of London – Ikey Solomon. Dickens never admitted shaping Fagin after Solomon.

Dickens was asked why he made Fagin a particularly odious Jewish character?

He answered – “it unfortunately, was true, of the time to which the story refers, that that class of criminal almost invariably was a Jew”…

“I have no feeling towards the Jews but a friendly one. I always speak well of them, whether in public or private, and bear my testimony (as I ought to do) to their perfect good faith in such transactions as I have ever had with them.”

1863, Eliza Davis, a Jewish balabusta, and her husband purchased a later Dickens’ home. She was not afraid to confront the now revered great British author, “liberal humanitarian,” about his antisemitism. She wrote to him.

“Charles Dickens the large hearted, whose works please so eloquently and so nobly for the oppressed of his country … has encouraged a vile prejudice against the despised Hebrew.”

Dickens was taken aback by the letter. He responded defensively.

Mrs. Davis wrote again asking Dickens to “examine more closely into the manners and character of the British Jews and to represent them as they really are.”

To Dickens’ credit, he did just that. He rewrote sections of Oliver Twist for future republication that toned down but did not eliminate the pejoratively tense word, “Jew.”

The docent and I agreed to disagree respectfully. He denied Dickens adultery and illegitimate child, the origin of his protagonist – Oliver from the Foundling Hospital a few blocks away and the willful antisemitism of Oliver Twist.

The Foundling Hospital Museum today, where abandoned infants found in the streets of London had been brought, rather than left to die of exposure or be eaten by dogs and pigs, is another Jewish story, for another time.

I left Dickens’ home recognizing that Dickens was a flawed man of the 21st century but a decent man of the 19th.

Confronting antisemitism, confronting bigotry, is not an epiphany, a sudden revelation or change. It is a process.

Dickens was willing to examine himself and his views. In a later book, Our Mutual Friend, Dickens created Riah, a Jewish character, a man as honest and noble of soul as any Christian.

The book did not sell well.

In the nearly two hundred years since Oliver Twist first appeared, it has been increasingly sanitized of its blatant antisemitism. Stage plays, musicals and movies have been produced, frequently by Jews.

Stripped of its bigotry, Oliver Twist is a good Christian story, a masterpiece of Victorian literature. Children’s versions of Oliver Twist do not have the word Jew in it.

The original version of Oliver Twist used to be required reading in public high schools. It is no longer the case. For that matter neither is the Diary of a Young Girl by Anne Frank.

*

Jerry Klinger is the president of the Jewish American Society for Historic Preservation.

Goldie Morgentaler of the University of Lethbridge in Alberta, Canada, is a professor of English literature. The work of Charles Dickens is a specialty. Here is her comment on Jerry Klinger’s article above:

“I have a few minor bones to pick (Oliver Twist is by no means Dickens’s masterpiece). But I don’t disagree with the general tenor of the argument. Dickens subscribed to the genteel antisemitism of his time and there is no getting around that, not even for admirers like me. He did try to write a more sympathetic Jewish character in answer to Mrs Davis’s complaint in Our Mutual Friend, but that portrayal is also antisemitic in the opposite way, namely, in its depiction of a saintly Jewish character without a blemish who dresses like some biblical character and has zero personality. In his letters, Dickens was full of prejudice against Jews, although I don’t think he knew very many personally. I’ve actually published several articles about the Jews in Dickens including one called “When Dickens Spoke Yiddish,” about the translations of Dickens’s novels into Yiddish, of which there were many. You may be surprised to learn that Oliver Twist was the most popular of Dickens’s novels for Jewish readers in Eastern Europe. That article appeared in Dickens Quarterly and can only be accessed through a university library, but it is quoted extensively here in an article from the Forward: https://forward.com/culture/448358/why-jews-loved-charles-dickens-and-even-fagin/. As the title says, Dickens was the favourite non-Jewish writer of east European Jews, so that too needs to be taken into account in any assessment of Jewish reactions to his work. My major disagreement with the author of the piece in SDJW is his final assessment that Dickens was a flawed man of the 21st century but a decent man of the 19th. Dickens was more than a flawed and decent man. He was a great writer, one of the greatest novelists ever to my mind. That is why we care about him and that is why we Jews are dismayed by his antisemitism. “

Way to go, Jerry. Do a similar study on Shylock.

Jerry… Having read many of your commentaries, literary offerings and musings over the years, and having found them informative and thought provoklng (as well as amusing on occasion), I found your commentary on Dickens and his character Fagin very, very interesting. I have always recognized the uncomfortable depiction of Fagin as scurilous and intentional. But your essay clarified (for me) the context of Dickens’ characters with the time of publication and the genuine nature of the person the author seems to have been.