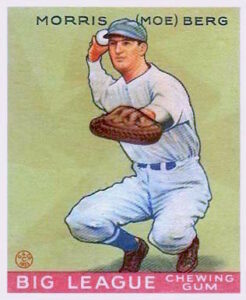

Moe Berg (March 2, 1902-May 29, 1972) was born as Morris Berg in New York City to pharmacist Bernard Berg and his wife Rose Tashker. The family moved in 1906 to New Jersey and at the age of 7, Berg played baseball for the Methodist Episcopal Church team. At age 16, he was graduated from Barringer High School and was selected by the Newark Star-Eagle to play third base on its high school team. Berg did his freshman year at New York University, then transferred to Princeton University, from which he graduated magna cum laude after learning seven languages: Latin, Greek, French, Spanish, Italian, German and Sanskrit.

On Princeton’s baseball team, he played shortstop. When an opposing player was on base, he and Crossan Cooper, the second baseman, communicated plays in Latin. In 1923, Berg signed a contract with the Brooklyn Robins, a forerunner of the Brooklyn Dodgers. Never a strong hitter, Berg batted .187 that season, and made 21 errors in 47 games. After the season, Berg went to the Sorbonne, where he enrolled in 32 different classes, and after the semester finished, toured Italy and Switzerland. He was sent to the minors in 1924.

In 1926, Berg returned to the major leagues, but missed several months in order to study for a law degree at Columbia Law School. In 1928, a series of injuries left the Chicago White Sox without a catcher, and Berg filled in. His 1927 debut in that position was against the fabled New York Yankees lineup that included Babe Ruth and Lou Gehrig. The battery of Ted Lyons and Moe Berg beat the Yankees 6-3, with Berg catching a wild throw from the outfield, then spinning and tagging Joe Duggan out at the plate. In 1928, he led all American League catchers in throwing out would be goniffs on the base paths.

In February 1930, Berg received his law degree. In the interim he tore a ligament in his knee, causing him to sit on the bench through much of the 1930 season as well as the 1931 season after being traded to the Cleveland Indians. In 1932, he made a comeback with the Washington Senators, with which he ended up second in the American League for double plays by a catcher and throwing out runners trying to steal a base.

In 1932, Berg went to Japan to teach baseball at Japanese universities, staying after his assignment to explore Japan, other parts of Asia, Egypt and Germany. In 1933, Berg was released by the Senators, but was picked up by The Cleveland Indians. In 1934, he joined a group of baseball All-Stars including Ruth, Gehrig, Jimmie Foxx, and Lefty Gomez to play against a Japanese all-star team. Berg was not nearly as good a player as his colleagues, but spoke some Japanese and was invited to address the legislature.

On a visit to Saint Luke’s Hospital, he went to the roof and filmed the city and port with his movie camera. This film was later turned over to American intelligence for use in bombing raids.

He played next for the Boston Red Sox, averaging fewer than 30 games in his five seasons. In February 1939, Berg was a contestant three times on radio’s Information Please quiz show, wowing audiences with the span of his knowledge. He terminated his appearances when moderator Clifton Fadiman started asking too many personal questions.

During World War II, Berg served in the Office of Inter-American Affairs under Nelson Rockefeller. He moved to the Office of Strategic Services’ Special Operations Branch, a forerunner of the CIA Special Activities Branch. From Washington, he monitored the situation in Yugoslavia. In 1944, he traveled around Europe, where he recruited Antonio Ferri to relocate to the United States to work on the development of supersonic aircraft. President Franklin D. Roosevelt quipped, “I see that Moe Berg is still catching very well.” Following the war, the CIA sent him again to Europe to learn what he could about the Soviet atomic bomb project.

Berg remained a bachelor for his entire life, living for 17 years with his brother Samuel, and later with his sister Ethel. Without explanation Berg declined to accept the Medal of Freedom from President Harry Truman, but his sister accepted it after his death and donated it to the Baseball Hall of Fame.

Tomorrow, March 3: Arthur Kornberg

*

SDJW condensation of a Wikipedia article