By Alex Gordon

HAIFA, Israel — The Jewish dream of equality with the peoples of the Diaspora has a long and bitter history. Emancipation expanded Jewish living space, occupation and education. They broke down the walls of the ghettos, came out of the local settlements and read many books in different languages in addition to, and gradually instead of, the holy books of the Jewish people. They fought for civil rights and equalization with non-Jews.

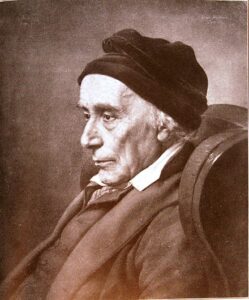

In Jerusalem (1783), Moses Mendelssohn described a version of Jewish life based on reason and consistent with Enlightenment ideas: one could be a Jew who kept the commandments and an enlightened German. He believed that Jews were a cultural, religious, but not a national group. The goal of the Jewish Enlightenment – the Haskalah he founded – was to synthesize Jewish and world culture. An “Enlightened” Jew could remain a Jew, enjoy all the civil rights of the country of residence, and receive non-religious education. But in Germany, Jewish liberalism became increasingly associated with Reform Judaism, and then with indifference to religion and with the authorized law of 1876 on the right to leave the Jewish community without the obligation to join another religious community, passed on the initiative of a Jewish deputy, the lawyer Eduard Lasker.

Calls for the assimilation of Jewish culture in world culture gave impetus to the assimilation of German Jews in German society and led to radical, unexpected, and unpleasant results for the philosopher: four of Mendelssohn’s six children and eight of his nine grandchildren were baptized.

One of the most striking examples of the results of Moses Mendelssohn’s activism is represented by the activities of his student and follower David Friedländer.

Friedländer was born in Königsberg in 1750. His father, Joachim Moses Friedländer, a wholesale merchant, belonged to a group of “patronized Jews.” In 1770 David Friedländer settled in Berlin, where he established a silk factory in 1776. He was appointed counselor to the state commission that reviewed the state of the textile industry. In 1809 he became the first Jew elected to the Berlin municipality.

A year after moving to Berlin, the 21-year-old Friedländer met Mendelssohn and became his pupil and friend. His marriage to the daughter of banker Daniel Itzig, one of Frederick II’s favorites, brought him into the circle of wealthy and influential families of court Jews. In 1778 Friedländer was among the founders of the Jewish public free school Education for Young Men, where Haskalah’s ideals were carried out. For 20 years he was the principal of this school. It was the first Jewish school that allowed the young poor, not just the rich, to read and speak German, acquire a general education and socialize with non-Jewish students.

The example of the Friedländer School proved contagious: twelve cities established similar schools, among them Dessau (Mendelssohn’s hometown), Hamburg, and Frankfurt. The school was called “free.” It was the epitome of liberation from the weight of allegiance to traditional Judaism. In 1779 Friedländer became an energetic advocate of Reform Judaism. Perhaps his main motivation was his dismay at seeing the wave of baptisms that had recently taken place. The reasons for shifts in religion of this type were pragmatic and mercantile. He was not an opportunist and could not accept the “surrender” of individuals to the religion of the majority.

From 1783-1812 Friedländer led the Prussian Jews’ struggle for equal rights. In 1787, King Frederick William II established a commission to reform the status of Prussia’s Jews. A delegation of Prussian Jewish communities under Friedländer’s leadership rejected the commission’s proposals because the Prussian authorities were actually unwilling to give Jews equal rights. Friedländer believed that in order to achieve emancipation, radical changes must be made in the way the Jewish religion was practiced. He believed it was possible to abandon the Talmud and the observance of many of the commandments. His refined Judaism began to morph into philosophical deism.

In 1799 Friedländer, along with other “Jewish landlords in Berlin,” sent an open letter to Wilhelm Teller, a high-ranking Protestant pastor. The letter stated that Jews and Protestants could unite on the basis of “pure” monotheism, without Jews being forced to accept the tenets of Christianity, which lacked rational justification. Friedländer wrote that Jews were willing to join the Protestant church if Teller accepted them on the basis of moral principles common to both religions, without them having to acknowledge the divinity of Jesus and be formally baptized. In return, the Jews would give up the characteristic features of Jewish worship.

Friedländer’s proposal of “dry baptism,” as it was later called, had in mind the formation of a common union of churches and synagogues. He hoped that a rational international religion could emerge from the Enlightenment movement and could unite Jews and Christians under one roof. Friedländer was opposed to Jewish acceptance of Christianity. He regarded the Jewish religion as an example of honoring the pure idea of the unity and holiness of God, unknown to any other people. In respecting biblical Judaism Friedländer was a faithful disciple of Mendelssohn. But he went beyond the teacher and away from Judaism. Like many other wealthy Jews in Berlin, he believed that a liturgical reform of the Jewish religion was necessary.

In a pamphlet entitled On the Necessary Changes in the Synagogue Ritual in Connection with the New Organization of Jewry in the Prussian State (1812) he proposed to remove from the prayers the mention of the coming of the Messiah, thus making a concession to the Christians. He translated the Jewish prayer book (siddur) into German, and generally considered it necessary to substitute Hebrew for German in the Jewish liturgy. He belonged to the few Reformers who thought it possible to abandon circumcision.

In Friedländer’s revision, Mendelssohn’s idea of remaining faithful to Judaism while integrating with the surrounding society underwent a major change. It is inconceivable that Mendelssohn was completely unaware of the feelings of his children and colleagues. In several respects he was probably partly responsible for them. Before his death in 1786 he seemed to have come to terms with the fact that his eldest son had abandoned his Hebrew studies and, like Friedlander, had ceased to observe the commandments of Judaism in the strict sense. Mendelssohn appointed Friedländer as director of his literary archive and dedicated his last book to him, calling Friedländer “my favorite assistant and supporter.”

Friedlander’s decision to turn to Teller was no accident. Teller was the most educated and respected Protestant minister in Germany. The Christianity he preached was rational and enlightened. If Teller had agreed with Friedländer’s idea, the realization of the project could have allowed Jews to gain civil and political rights denied to them without adopting Christian principles. This would have equalized the Jews with the baptized Jews. Friedländer’s initiative went much further than what Mendelssohn could have imagined and envisioned. In his books, Mendelssohn described Judaism as a rational religion. However, he never doubted the correctness of halakha. The call for unity between the Protestant and Jewish religions was a departure from Mendelssohn’s teachings.

Teller’s response to Friedlander’s open letter was negative. As a philosopher, Teller found sympathy for Friedländer’s proposal for the unification of religions. As a spiritual shepherd of the praying people in the Berlin cathedral, he regarded the proposal with contempt. The language of the reply was arrogant. The priest forgave Friedländer’s ancestors who had rejected Jesus, but he did not forgive Friedländer’s own refusal to recognize Christ as savior. In Teller’s opinion, Friedländer and his fellow Berlin landlords should recognize Christianity as the highest religion, morally superior to the faith of the Jews, used mainly for ceremonies. The representatives of Protestantism unanimously condemned Friedländer’s address. Their language was harsh; anger over “his insolence” did not subside for months. The priests were outraged by Friedländer’s assertion that Jesus was merely a rabbi or Jewish prophet.

Later, too, Jewish reaction to Friedländer’s proposal became largely hostile (“shameful act,” attempted “defection” to the enemy camp). However, there was no substantial public criticism. Friedländer was soon elected head of the Jewish community in Berlin. As the official representative of the Jews, he fought against their inequality on all fronts: “In civil and criminal matters, the oath of a Jew must have the same meaning as the oath of any other person. The Jew is as much a man and citizen as any other, and nothing in his religion makes him less trustworthy than a Christian. How many criminal cases there have been in which Christians have declared in court that they did not think they were committing a sin by killing a Jew! How does this characterize Christian morality? There is only one way to destroy these prejudices, as dangerous as they are shameful, in the minds of all men: equality before the law, the same trust in all, the same penalties for perjury.”

In 1812 a long-awaited event took place in the life of German Jews: in March the restrictions on the rights of Prussian Jews were abolished. Jews were recognized as equal citizens of Prussia. Liberal tendencies brought by Chancellor Karl August von Gartenberg, Friedländer’s friend and patron, convinced Friedrich Wilhelm III to implement the emancipation of the Jews. The order to grant equality to the Jews led to a dramatic increase in the number of baptisms, which doubled between 1812 and 1819. Parallel to the baptisms was an outbreak of fervent patriotism among Prussian Jews: a very large number of Jewish volunteers actively participated in the German war against Napoleonic France in the ranks of the Prussian army.

After Napoleon’s defeat, which brought emancipation to the Jews in a number of places, the equality order was revoked after three years in effect. While the emancipation order was in effect, Friedländer was in a state of euphoria. The happy reformer urged young Jews to volunteer for the army: “A marvelous feeling we have now: we have a homeland! We are happy to call this place, this piece of land – our homeland. […] Together with other soldiers we will fulfill our great task. They will not be able to take away from us the title of brother, which we have rightfully received.”

The temporarily emancipated Jews began to reform Judaism with vigor. The annulment of the equality order did not cool the Jews’ ardor to establish synagogues of a new, “lighter” type. The government initially closed the first non-traditional synagogue. Reform-type prayers were held only in private homes. The king was frightened by the reform that the Jews were intensively producing. He had two reasons for this line of behavior: 1) he feared that the reform would prevent Jews from being baptized, and 2) the “enlightenment” might attract Christians to Judaism or lead to reform in the Lutheran church.

The rapid progress of the Jews’ quest for equality led to unrest and protests by Christians. On August 2, 1819, pogroms broke out in Würzburg, instigated by students at the local university. In Würzburg, a mob of laborers, artisans, merchants and students broke into stores owned by Jews. The rioters beat Jews with shouts of “Death to the Jews!,” looted and destroyed stores. Two Jews were killed and about 20 were injured. Authorities quelled the riots to prevent the massacre. About 400 Jews of the city were forced to flee and live for several days in the surrounding villages in shanties, as their ancestors did upon leaving Egypt.

The pogroms spread to other towns and villages in Bavaria, and from there to the center and southwest of Germany. Hundreds of Jews fled from Hamburg, seeking refuge in Denmark. There had not been such persecution of Jews since the Middle Ages. On August 18, 1819, Friedrich Schlegel, writer and philosopher, one of the founders of Jena Romanticism, wrote to his wife Dorothea, the baptized daughter of Moses Mendelssohn, aunt of the composer Felix Mendelssohn, that the events taking place were “a return to the dark Middle Ages.”

David Friedländer died in Berlin in 1834. The emancipation of German Jews was not achieved. It is surprising that the Jewish believer Moses Mendelssohn, thinker and Jewish educator, failed to take into account that, unlike other religions, Judaism is inextricably linked to Jewish nationality. Christianity and Islam require believers to fulfill the precepts and dogmas of these religions and do not see them as people of a particular nationality. Judaism requires belonging to the seed of Abraham, Isaac and Yaakov – the chosen people. The gap between Judaism and belonging to a Jewish nationality was to lead to a departure from the Jewish religion and assimilation.

Emancipation contained an internal insurmountable barrier preventing the Jewish people from becoming like everyone else. The effort to sever the link between Judaism and belonging to the Jewish nation was a campaign of national self-aggrandizement, a hysterical confusion, an act of self-deception. Attempts to normalize Jewish life among the surrounding nations were doomed to failure, because Jewish membership itself was a challenge to the surrounding nations. The Jews’ longstanding efforts to normalize their oppressed situation, where the main thing was to maintain religious affiliation with the Jewish people and to join others, were inconsistent and largely dictated by self-deception and/or the need for salutary deception of non-Jews. Racial antisemitism ended the illusions of achieving Jewish equality.

The Enlightenment and emancipation individualized the Jew, depriving him of his national “we.” his collective being. The dual way of life of Enlightenment Jews led to their double defeat. Non-Jewish society treated the rising, masquerading, mimicry Jews with distrust and dislike. Jews began to treat their own people worse and worse. The Jewish world of tradition, community, locality, ghetto, which had protected the Jew, was crumbling. The Jew found himself alone with the alien and hostile non-Jewish world. He cut off his roots and turned himself into a man from nowhere, a copycat, an imitator of German culture. The bifurcation of the people’s soul required by Mendelssohn and Friedländer to normalize Jewish life did not solve the old problem, but created a new one.

*

Alex Gordon is a native of Kiev, Ukraine, and graduate of the Kiev State University and Haifa Technion (Doctor of Science, 1984). Immigrated to Israel in 1979. Full Professor (Emeritus) of Physics in the Faculty of Natural Sciences at the University of Haifa and at Oranim, the Academic College of Education.