I’m a German and I want to stay one, I’m a Jew and I want to stay one, I’m a socialist and I want to stay one. […] Everything I have written, I have signed my name. I am fighting for justice against my own country, which I love. — Theodore Lessing

By Alex Gordon

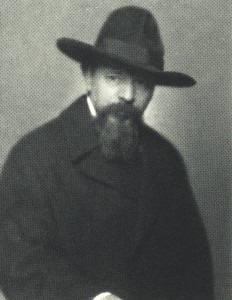

HAIFA, Israel — On February 8, 1872, the German philosopher Theodor Lessing was born in Anderten near Hannover. He was born into an assimilated Jewish family. His father was a prosperous physician in Hannover and his mother was the daughter of a banker. Lessing recalled his school years as miserable: ‘This humanistic German gymnasium, specializing in patriotism, Latin and Greek, […] this institute for the promotion of stupidity, half of it built on white-collar jumping, the other half on false platitudinous German nationalism, was not only incredibly irresponsible, it was utterly boring. […] Nothing, nothing could ever make up for what those fifteen years had destroyed in me. Even now, almost every night I am reminded of the torture of my school days.”

In 1892 Lessing entered the medical faculty in Freiburg, then transferred to Bonn. From 1895 he studied psychology with Theodor Lipps in Munich, and in 1899 he received his doctorate in philosophy at Erlangen. In 1895, while a student in Freiburg, he converted to Lutheranism. In 1898 he returned to Judaism, and in 1900 became a Zionist and a critic of assimilation. In 1906 he published his first philosophical work, Schopenhauer, Wagner, Nietzsche: An Introduction to Modern German Philosophy.

His plans of habilitation [post-doctoral degree] at the University of Dresden were canceled in the face of continuing public outrage over the influence in academia of Jews, socialists, and feminists. In 1906 he traveled to Göttingen to receive habilitation from the philosopher Edmund Husserl. But this plan also failed. On his return to Hannover in 1907, he became professor of philosophy at the Higher Technical School.

With the outbreak of World War I, Lessing was called up for medical service. At this time he wrote his famous essay History as the comprehension of the senseless. Its publication was delayed by the censor until 1919 because of its uncompromising anti-war stance. In his memoirs of World War I, published in Prague in 1929, he cynically wrote: “I became a draft dodger. All through the war, all four years I was sent summonses every month. It became harder and harder to dodge the draft, but I kept inventing and inventing valid reasons.”

“I became skeptical of the beauty and greatness of the German mind. It is different in England. The average person there is more eccentric and unique than we are,” Lessing wrote in an essay on English drama, written during a period of growing discontent between the two nations and reprinted in Culture and Nerves.

After the war he returned to lecturing in Hannover, and from 1923 he took an active part in public life, publishing articles and essays in the Prager Tagblatt (Prague daily) and the Dortmunder Generalanzeiger (Dortmund general newspaper). He quickly became one of the leading political writers of the Weimar Republic. In 1925, he drew attention to the fact that serial killer Fritz Haarmann was a spy for the Hannover police, as a result of which he was not allowed to cover the trial.

Theodor Lessing was one of the most hated men in the Weimar Republic. As a Jew, he was, unlike the German Jewish patriots Walter Rathenau and Fritz Haber, an anti-patriot. During the 1925 German presidential election, he infringed on one of Germany’s holiest shrines, Field Marshal Paul von Hindenburg, a patient of his physician father. In the Prague anti-German newspaper Prager Tageblatt, Lessing published an article Zero – Nero? criticizing the honored field marshal, describing him as a “simpleton,” a “subhuman,” and a “ferocious wolf.” Lessing argued that Hindenburg would be another “Nero”: “According to Plato, philosophers should be the leaders of men. In the case of Hindenburg, it is not a philosopher who will ascend the throne. It’s just a symbolic sign, a question mark, a zero. We could say to ourselves that it is better Zero than Nero. Unfortunately, history shows that behind every zero there is a future Nero.”

Field Marshal Hindenburg, future president of the Weimar Republic, was Germany’s top military leader during World War I – commander of the Eastern Front, later Chief of the General Staff. Both the people and the troops loved him. Lessing’s treatment of the hero of the German nation aroused hatred for the author of the article and led to a rise in popular resentment against the Jews. He denounced Hindenburg and accurately predicted the imminent establishment of a dictatorship in Germany with the assistance of the Field Marshal. He declared that whoever voted for Hindenburg in the election would vote for Hitler.

This article was disliked by nationalists, and his lectures were soon disrupted by protesting antisemites. Lessing received limited public support, and even his colleagues said he had gone too far. On June 18, 1926, Prussian minister Karl Heinrich Becker gave in to public pressure, expelling Lessing indefinitely from the university with a reduced salary. Lessing was deprived of the chair of professor of philosophy at Hannover, which he had held for 18 years.

In the presidential election of 1932, he opposed the nomination of Hindenburg as president of the Weimar Republic. A deserter, an abuser of national hero Hindenburg, and a critic of Nazism, Lessing became one of the greatest enemies of the new government: when the Nazis won the 1933 election, President Hindenburg commissioned Hitler to form a government. Lessing’s political ideals, as well as his Zionism, made him a very unpopular figure in Nazi Germany. On January 30, 1933, the Nazi Party entered the government, and on March 1, Lessing and his wife Ada fled to Marienbad in Czechoslovakia, where he continued to write for German-language newspapers abroad. But in June the Sudeten newspapers reported that a reward had been announced for his capture.

In the summer he participated in the 18th Congress of Zionists in Prague. He lived in Marienbad at the Edelweiss Villa of a local Social Democratic politician. On August 30, 1933, he was working in his office on the first floor when he was shot by his assassins, Sudeten Germans, Nazi supporters Rudolf Max Eckert, Rudolf Zischka and Karl Hönl. After the assassination, they fled to Nazi Germany. Lessing died of his wounds on August 31.

In 1930 Lessing published his major book Der jüdische Selbsthaß (Jewish Self-Hatred), a historical and psychological study of Jewry as a minority in the Diaspora. He apparently took the basic idea for the book from the life of the psychologist, baptized Jew Otto Weininger, and from one of his articles. In the article, “On Henrik Ibsen and his work ‘Per Gynt'” Weininger wrote of Nietzsche as an individual who had a particular hatred of himself. Lessing adopted the concept of “self-hatred” (Selbsthaß) from this article to explain the psychic peculiarities of many Jewish cultural figures, including Weininger himself. According to Lessing, this inwardly directed aggression motivated both Weininger’s conversion from Judaism to Protestantism and his suicide.

Lessing studied self-hatred on himself. During his student years, he, a typical German Jew who had not received a Jewish upbringing, had been influenced by antisemitism, imbued with hatred for his people, and converted to Lutheranism. Feeling that the antisemitic attacks against him did not become weaker, he returned to Judaism, exhibiting sympathies for Zionism. He understood “self-hatred” as a “life-killing disease,” which psychologically consists of adapting to the negative image of Judaism held by non-Jews.

Lessing saw the Jews as an Asian people displaced on the European stage and forced to occupy a position between the cultures of the two continents. He noted that the weakness of the Jews lay in their detachment from the soil, as a result of which this people had become overly spiritualized and decadent. He saw the solution to the Jewish problem in a return to the exhausted soil of Palestine. The restoration of the land and the people, he, as a member of Poalei Tzion (Workers of Zion), saw in the synthesis of socialism and Zionism.

In the book The Jewish State (1896) Theodor Herzl criticized opponents of the plan to create a Jewish state in Palestine, calling them “disguised antisemites of Jewish origin.” He was the first to speak not only about the creation of a Jewish state, but also about the phenomenon of Jewish antisemitism.

Jewish self-hatred was provoked by the hatred of Jews by the dominant population of the host countries in which Jews lived, and where they were considered a lower-ranking minority – the “other”, the “born strangers.” Self-hatred arose as a response to the pushing of Jews by the dominant nation to the margins of society. This feeling arises in Jews as a reaction to the way the dominant nation sees them. They radiate restlessness and anxiety, pushing away their belonging to their own people and artificially elevating themselves above their tribesmen. Jewish self-hatred was a neurotic reaction to the growing power of antisemitism and an expression of the fear of fighting it for spiritual national self-assertion.

Lessing counted the Austrian satirical writer Karl Kraus among self-hating Jews, calling him “the most eloquent example of Jewish self-hatred.” His conclusion was apparently based on Kraus’s criticism of the liberal, cosmopolitan press, which was run by assimilated Jews and to which Kraus himself belonged. Kraus wrote: “My hatred of the Jewish press is exceeded only by my hatred of the antisemitic press, while my hatred of the antisemitic press is exceeded only by my hatred of the Jewish press.” Kraus’s satire was imbued with the spirit of a cosmopolitan refugee from Judaism.

He passionately opposed a review of the Dreyfus case and criticized sympathy for him because his “guilt or innocence is not proven.” In his view, the campaign in defense of the accused deserved more censure than antisemitic attacks on him. Krauss’s attacks on Heine, Dreyfus, Freud, Herzl and colleagues in the liberal press betray his Judeophobic attempts to “purge” himself of Jewishness.

The term “Jewish self-loathing,” coined by Lessing, became popular after the publication in 1986 of the book Jewish Self-Hatred by American historian Sander Gilman. Gilman writes, “Jews see the way the dominant nation perceives them, and through cleavage project their concerns onto other Jews for self-soothing.” This projection creates a dichotomy: “self-hating” Jews seek to make themselves “good” Jews-exceptions different from the stereotypical “bad” Jews. The self-hating Jew is copying the attitudes of antisemites toward his people. The self-hating Jew is convinced of the inferiority of his nation’s culture and seeks to borrow other people’s language, other people’s art, other people’s traditions.

Philosopher, historian, psychologist, socialist, Zionist, antipatriot and antihero of nationalist Germany, researcher of Jewish self-hatred fell victim to anti-Jewish hatred. He was one of the first victims of the Holocaust.

*

Alex Gordon is a native of Kiev, Ukraine, and graduate of the Kiev State University and Haifa Technion (Doctor of Science, 1984). Immigrated to Israel in 1979. Full Professor (Emeritus) of Physics in the Faculty of Natural Sciences at the University of Haifa and at Oranim, the Academic College of Education.