By Alex Gordon

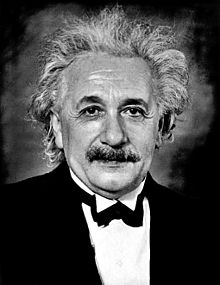

HAIFA, Israel — Albert Einstein, a third-class clerk at the Bern Patent Office and a part-time graduate student at the University of Zurich, published two articles on the special theory of relativity in 1905. With this publication began a revision of the concepts of time and space. In Einstein’s view of the world, which began to open up with his work on the theory of relativity, one found religiosity and irreligiosity.

Einstein undoubtedly identified himself with the Jewish people, “My connection with the Jewish people has been my strongest human bond since I began to be fully aware of our precarious position among the nations of the world.” He could not forgive the Germans for the Holocaust and did not wish to do business with them afterward. He wrote to Stalin in 1947: “As an old Jew, I urge you to find and return to his country Raoul Wallenberg, […] who, at the risk of his own life, worked to save thousands of my unfortunate countrymen.”

In 1952, an attempt was made in Israel to appoint Einstein as president of Israel. When he declined, Ben Gurion remarked, “Thank God he didn’t accept.” He was probably referring to Einstein’s pacifist views, which were not suitable for a Jewish state that had to be constantly at war with enemies who wanted to destroy it.

In 1921, Einstein wrote to the Jewish physicist Paul Ehrenfest: “Zionism represents a truly new Jewish ideal and can restore to the Jewish people the joy of existence.” He joined the campaign to raise funds for the establishment of a Hebrew University in Jerusalem. Excitement about the successes of the Zionist movement, real and expected, Einstein expressed in February 1923, when he arrived in Palestine. On February 13, walking between the rows of Jerusalem school students who greeted him warmly, Einstein said: “Today is the greatest day of my life. A great epoch has come, the epoch of the liberation of the Jewish soul; this was achieved by the Zionist movement, so that now no one in the world is able to destroy what has been achieved.”

Ben Gurion’s opinion of Einstein’s inappropriateness for the position of president of Israel could also be related to the great physicist’s attitude toward religion.

Religious Jews were hardly happy with Einstein’s “religiosity.” In a letter written a year before his death, he characterized himself as follows: “I am a deeply religious non-believer. […] This is something like a new kind of religion.” The portrayal of Einstein as a devout Jew who does not keep the commandments is a popular myth, completely unnecessary to strengthen Judaism. Jews do not need to strengthen Judaism by attributing Einstein to it. Such an endeavor is like the creation of idols and paganism, which Judaism rejects. It both simplifies Judaism and simplifies Einstein’s view of religion. Jews who reinforce their religiosity by citing a long list of brilliant Jews are engaging in idolatry.

Einstein believed that there are three kinds of religion: the religion of fear, the moral religion, and the cosmic religion. The religion of fear is the religion of the totem, which requires appeasement of the god, making sacrifices to him so that he protects man from hunger, wild animals, disease, epidemics, from neighboring hostile tribes, from natural disasters, and from death. Moral religion requires man to behave in a certain way or else he will be punished by the Almighty. There are no religions of fear and moral religions in pure form, but Einstein believed that the transition from the religion of fear to moral religion is progress, and that at higher stages of development of social life moral religion prevails.

Cosmic religion knows neither dogma nor God, created in the image and likeness of man. Einstein recalls that he “although the son of completely irreligious (Jewish) parents, came to a deep religiosity, which, however, already at the age of twelve was abruptly cut short. Reading popular science books soon led me to the conviction that many things in the biblical accounts could not be true.” He had not been given the rite of bar mitzvah, Jewish adulthood. He saw the rudiments of a cosmic religious sense in some of David’s psalms and the books of the Hebrew prophets, but this did not convince him to fulfill the commandments of Judaism.

According to Einstein, the world is governed by the laws of reason and comprehended by reason. He “did not believe in a God who was concerned with the welfare and moral behavior of human beings.” In one of his letters, he wrote, “I am convinced that a clear realization of the paramount importance of moral principles for the improvement and ennobling of life does not need the idea of a legislator, especially a legislator acting on the basis of rewards and punishments.” The Jewish believer would hardly agree with an attitude toward God taken from physics, which operates only with observable quantities: “Assuming the existence of a non-perceivable being does not make it easier to understand the order we find in the perceived world.”

Einstein believed in natural harmony governed by the laws of nature. Such a religion is akin to Spinoza’s philosophical concept of God, who believed that there is no creator God, but rather a God-creation, that is, nature is harmonious and develops according to the laws, not the will of the creator. The creator is identical with creation, hence there is no creator separate from creation. “I believe in Spinoza’s God, who manifests Himself in the harmony of all existing things, but not in a God who occupies Himself with the fate and deeds of men,” wrote Einstein. A cosmic religion cannot have a church, just as Spinoza had no church. According to Spinoza, everything in the world is governed by absolute, logical necessity. So evil is as inevitable as good. Therefore, the Christian church treated him as one of the worst sinners that ever existed.

Jean-Jacques Rousseau believed science had undermined reality. Disagreeing, Einstein explained: “I can find no better expression than ‘religion’ to denote belief in the rational nature of reality. I maintain that a cosmic religious feeling is the strongest and most sublime motive for scientific inquiry.” He believed that the brilliant scientists of all times were marked by a cosmic religious feeling. He was a cosmotheist.

The view of physics before Einstein, with its rigid determinism, the cult of the principle of causality, and man’s faith in Newton’s physics, which became a kind of substitute for traditional religion, was described by Bernard Shaw in his play Too True to be Good: “In this was my faith. Here I found my dogma of infallibility. I who despised both the Catholic with his vain dream of responsible free will and the Protestant with his claim to personal judgment.” The uncertainty principle, the probabilistic interpretation of quantum mechanics, the revision of the role of measurement in the microcosm and the relation to independently existing matter have shaken up the concept of predestination. The revision of the so-called “common sense,” realized by the probabilistic interpretation of quantum mechanics, caused Einstein’s own resistance: “I do not believe in God playing dice.”

However, Einstein’s own ideas dealt the traditional common sense no less a blow than quantum theory. Denial of the concept of simultaneity, relativity of duration, reduction of the size of bodies in very fast motion, slowing down of time in fast-moving systems, transformation of matter into energy, assertion that the geometry of the Universe is not ordinary Euclidean, but non-Euclidean due to the presence of gravitational fields, rejection of Newton’s empty space and objective, independent time changed the ideas about nature and refuted the empirical intuition of direct sense perception.

Those who, following Newton, believed that absolute space was identical to “God’s sensory apparatus” were disappointed by the theory of relativity. Newton developed a concept of space in which there were no places or boundaries. In the Jewish-Christian worldview, absolute and empty space was once introduced: the state of the world before the act of creation. St. Augustine was very concerned with the problem: If the universe was completely empty before the act of creation, why did God delay so long before He decided to create the world? His answer in the Confessions is well known: “Before the creation of heaven and earth there was no time.” This meant that in the empty space that existed before the creation of the world, time did not exist, and there was no point in asking what God was doing before the creation of the world. Absolute and infinite space, on the existence of which Newton insisted in his mechanics, is, from the point of view of the theory of relativity, an incorrect concept.

After Einstein’s work, space ands time were no longer the passive background against which events occur. We can no longer imagine space and time as lasting forever, regardless of what happens in the universe. Einstein expressed his criticism of the accepted view of space, time, and matter in popular form: “If we suppose that one day all matter will disappear from the world, then, as was believed before the theory of relativity, space and time will continue to exist in an empty world. But according to the theory of relativity, if matter and its motion were to disappear, there would be no more space and time.”

Einstein’s attitude to Judaism is ambiguous: “Jewish religion is the way to the elevation of ordinary life. […] There is no contradiction between our religious view and science.” In his view, “Judaism is not a faith: the Jewish God is nothing but the negation of prejudice. […]. But He also tries to base the moral law on fear, which is a frustrating and unreliable attempt. And yet it seems to me that the robust moral tradition of the Jewish nation has largely jettisoned that fear. It is also clear that ‘serving God’ means ‘serving life’.” The best among the Jews, mainly the prophets and Jesus, fought tirelessly for this goal.” The view of Jesus as “the best among the Jews” is hardly consistent with the Jewish religious worldview.

On January 2, 1915, in the midst of World War I, Einstein wrote to his Swiss colleague Edgar Meyer: “Why do you write to me, “God must punish the British?” I have no intimate connection with Him or with them. I only notice with deep sadness that God punishes so many of his children for the great foolish things they do, for which He alone is responsible. In my opinion, His non-existence alone can justify Him.”

*

Alex Gordon is professor emeritus of physics at the University of Haifa and the author of 10 books. He has been published in 91 journals in 17 countries in Ukrainian, Russian, Hebrew, English, French, and German.