Editor’s Note: This is the 29th chapter in Volume 3 of Publisher and Editor Donald H. Harrison’s 2022 trilogy, “Schlepping and Schmoozing Along the Interstate 5.” All three books as well as others written by Harrison may be purchased from Amazon.com

Editor’s Note: This is the 29th chapter in Volume 3 of Publisher and Editor Donald H. Harrison’s 2022 trilogy, “Schlepping and Schmoozing Along the Interstate 5.” All three books as well as others written by Harrison may be purchased from Amazon.com

Schlepping and Schmoozing Along the Interstate 5, Volume 3, Exit 71 (Basilone Road): San Onofre Nuclear Generating Station

Before you reach the Basilone Road exit of the Interstate 5, you will pass two domes on the San Onofre Nuclear Generating Station (SONGS) on the left. In the process of being deconstructed, it is permanently closed to the public, but stories remain about what it was like to work there. Julius Katz tells one of them.

CAMP PENDLETON, California — Like many interesting things that happened in his life, Julius Katz had no premonition that he would spend 25 years working in various jobs at the San Onofre Nuclear Generating Station (SONGS) before retiring in 2002 at the age of 65.

CAMP PENDLETON, California — Like many interesting things that happened in his life, Julius Katz had no premonition that he would spend 25 years working in various jobs at the San Onofre Nuclear Generating Station (SONGS) before retiring in 2002 at the age of 65.

With the economy in recession and unemployment at a 40-year high, Katz’s management position at the now bankrupt Builders Emporium was eliminated. As days turned to weeks pounding the pavement, he was desperate to provide for his family – he needed a job immediately. At the suggestion of a family member, he presented himself for a job at Local 89 of the Laborers International Union of North America (LiUNA). On the fourth day after paying his $100 membership fee, he was sent with a team of laborers to a parking structure in La Jolla that needed to be demolished. He was given a 95-pound jackhammer and instructions how to use it. The following week, there was a call for 35 people for another job. The 35th person called wasn’t there, and Katz had number 36.

“We were sent to San Onofre. I drove up in my car, an old Volvo, parked, registered, got paperwork and my badge, and went inside,” Katz related during an April 2022 interview. A fellow named Hector instructed ten members of the group, including Katz, to follow him to a trailer that was used for an office. Unable to say “Julius,” Hector renamed Katz as “Julio,” utilizing the Spanish pronunciation – a name that Katz answered to for the next 25 years.

His first assignment was to go down a manhole by the construction trailers outside the nuclear generating station and stop a trickle of water. It took several hours to locate the source of the leak and then to stanch it. That cleared the way for a painter with a pint of paint and a paintbrush to descend into the pit. Swish, swish, and the painter climbed back out. His whole job was to paint a handle.

Next, Katz was assigned to move furniture, paint offices, and locate items in the facility that were needed elsewhere. When 30 of the 35 workers were laid off, Katz figured he was next. He was sure of it when his name was called over a loudspeaker and he was ordered to report to the office. However, the boss told him, “I can tell you haven’t experienced a lot of construction, but you are really good with people, and you sure know how to do paperwork. I’ll tell you what I’m going to do. I need a person on the swing shift, 12 to 7, and I am going to make you the foreman. I’m going to bump your salary up $2 an hour and I’m going to give you a crew of 14 people.”

“I said, ‘Oh, okay,’ and I go home and say, ‘Hey, Judy, I’m there three weeks and I am a foreman.’ The next day I introduce myself to a crew of guys, all with decades of experience.”

Such was life before the nuclear generation station went online. However, when the reactors went online – or “hot” in the vernacular – “the entire aura of the place changed,” Katz said. “Everybody had to get a drug test and, all of a sudden, a lot of people disappeared. Afterall that was said and done, everything was fine, and things were running normally. Then they did away with my shift, so I went back to days. I had picked up several skills. One of them was becoming a core driller, who runs a machine that cuts holes in concrete, so cables and pipes can pass through. I had worked my way into becoming an assistant with an experienced core driller and he taught me how to do it.”

Katz related that he was “sent out with this big machine and I would pick a partner. We would drill holes through walls. Sometimes we had to hang from the ceiling in seats. Thank God, no one got hurt. I was no longer a foreman anymore. I was just a schlep. Then one day the boss calls me in and says, “We are having a problem on graveyard; I want you to run the graveyard shift.” Katz said he protested that there were 50 different crafts on graveyard; he was not prepared to supervise them. His supervisor responded, “You are running the central tool room on graveyard. It is a cherry thing to do. You will work 6 ½ hours, and you will get foreman’s pay and a $2 bonus.” This lasted for six months and “then I went back to days and became an official core driller and jack of all trades.”

Katz often worked inside the nuclear generation station, which workers nicknamed the “can.” That required wearing a nuclear uniform. “First you put on pajamas, then you put on a special suit, then you put on booties over your tennis shoes,” he said. “You cover your head with a hood and depending where you go, you put on a clear plastic mask. Everyone carries a dosimeter (for measuring radiation) that is attached to your badge. Every month they would read it to see what kind of dose you got. When you went into the can, you had to wear a special radiation device. The can was divided into various areas — some of which were roped off. There were purple areas that you couldn’t go into because they were high-radiation areas.”

When entering the “can,” workers would be accompanied by a health physics person who would make sure they understood where they could and could not go. Some places you could go inside but only for a limited time, such as 10 or 20 minutes.

“Tools that were used in the radiation area were marked with a big purple slash,” Katz said. “If you saw something with a purple slash, you knew that you could use it in that area. I would get my material from the hot tool room, do my job, and then I would come out, and they would take a reading of my dosimeter. I would usually take a shower after I came out, then get dressed in my regular clothes, and then I would leave.”

“They were very protective of people who went into the can and God forbid if you were caught stepping over the line onto a radiation area – you could get fired immediately. There wasn’t any question because they were set up so any idiot would know you can’t go pass that boundary. There were three units – Can 1, Can 2, Can 3 – and each unit had a container; the big domes that you see are containments.”

Katz said he had been in the can “filling holes for radiation” on the day that he was laid off for a year. Katz said having him do the job on the day they knew he would be laid off seemed particularly inconsiderate. He worked during the layoff at an office furniture store and when he returned to San Onofre, he worked as an apprentice carpenter, helper and “schlepper.” He also did concrete work, and “never became a foreman again.” On his 65th birthday, Sept. 30, 2002, he received a jacket and a pocket knife for his retirement and “that was the end of my San Onofre days.”

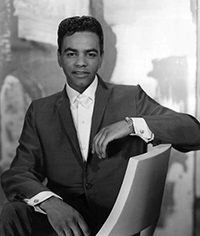

Katz’s life can be divided into his time before San Onofre when he served as a roadie for popular singer Johnny Mathis, and after San Onofre when he and Judy enjoyed traveling together, particularly on cruise ships, until she passed away.

His pre-San Onofre days started in The Bronx, New York, where his immigrant parents, Sidney and Regina, respectively from Romania and Hungary, settled approximately in 1935 after living several years in Cuba. His uncle Dave arrived in the U.S. earlier, and the family has a picture of him in a U.S. Army uniform during World War I, “but nobody in the family has been able to clarify how or when he got here,” Katz said. “Everybody connected with that era has passed away or were killed in the concentration camps. My father’s family was killed; my mother lost two sisters.”

The family lived in a six-story walkup until with the help of an aunt they were able to move to a triplex. “My aunt rented out two stories above us and we lived on the ground floor. It was there that my sister Elaine was born. My uncle David, myself, and my brother Stanley at one point shared one bed, believe it or not. At the end of World War II, my mother’s niece Magda married Fritzi, who came home after the war. He made it through the Normandy invasion and when she got pregnant with no place to live, they moved into one bedroom. So, we had three of them in one room, three of us in one big bed, and my little sister lived in a closet – I swear to God. You could touch the walls with both hands. My folks lived in another bedroom.”

His father and uncle purchased a dry cleaning establishment in Manhattan, and before long purchased a second store in a neighborhood where many people spoke Spanish. As his father had learned that language in Cuba, he developed a good rapport with his customers. “This, incidentally, was the location of my first job as a young teen, as the occasional bag man or local numbers runners that used my father’s business as their storefront.”

His mother “took care of the house, would feed us children, and when dad and Dave came home, she would feed them. She was always cleaning. The nice part about it on holidays, Thanksgiving, Passover, birthdays, she would somehow clear the living room and we would have 20-30 people there at a time. My bar mitzvah we had a house full of people.”

After graduating from DeWitt Clinton High School, he attended City College of New York’s business school. He emphasized classes in advertising, which led to a mailroom job with the Dowd, Redfield and Johnstone advertising agency. With young men being drafted for the Korean conflict, Katz signed up for the Army reserve and after six months active duty stateside, “played soldier every summer” until his enlistment was up. After the service, he and a friend decided to move to Los Angeles where they stayed with an old girlfriend and her husband until the husband told them to leave. They found themselves an apartment at a “swinging singles” place in Hollywood, “where people just walked into each other’s apartments and sometimes dove into the swimming pool from the second-floor balcony.”

From there, Katz and three friends rented a home about three blocks below the Hollywood sign, even though no one was actually working. Everyone was collecting unemployment. To pay the rent, they had “chip-in” rent parties at their home. One of their roommates got a job at the Dolores Drive-In on La Brea Avenue. Normally, Katz or another roommate would drive him to and from work. But one day, coming home, he stepped out of the passenger side of a new Jaguar XKE. Katz’s girlfriend poked him in the ribs. Look, she exclaimed, the fellow driving was Johnny Mathis. Katz, in the kitchen, made a dinner of spaghetti and meat sauce for his roommates, their girlfriends, and Mathis. The next day Mathis’ agent called, thanking them for their hospitality, and inviting them to the Ambassador Hotel for the opening of Mathis’ show. A limousine picked them up and they had a scrumptious dinner, on the house, and went following the show to an after-concert party.

“Somehow, we became close friends with him,” Katz marveled. “We’d go bowling at the LaCienega Lanes. He had a house you could not believe; the roof opened up over the pool and he had a jacuzzi you could put 25 people in – it was so big. Somehow my buddy Mark became his stage manager, and I was appointed his lighting director, which was a baloney title. So, we started traveling with him, here, there, and everywhere. We did a stint in Las Vegas and they sent a limo for us. We stayed there for the two or three-week performances and everything was paid for. All I did was sign my name.”

Mathis’ birthday is September 30th, the same day as Katz’s, only Mathis is one year older. Although the group broke up after a falling out between Mathis and Mark, “for the longest time, I would correspond with him and we would send birthday cards.” When Katz’s mother and sister came to California to visit, they got to visit Mathis at his home and “he gave my sister 12 autographed albums, which she still has today and which she treasures.”

Next Katz went to work at the May Company’s advertising department where he did copywriting, proof reading, and transporting the proofs to and from major newspapers in the greater Los Angeles area. “It wasn’t exactly Mad Men but there were many three-martini lunches, and I had a great time.” That is, until May Company decided to outsource its advertising department. The next step in his career was the Builders Emporium, followed by San Onofre, which would encompass the lion’s share of his work history.

As of April 2022, Julius lived in the Del Cerro neighborhood of San Diego. He was a doting father of four and grandfather of five.

*

Donald H. Harrison is publisher and editor of San Diego Jewish World. He may be contacted via sdheritage@cox.net