By Alex Gordon

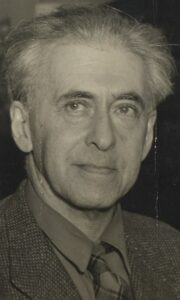

HAIFA, Israel — The hand extended to Ilya Ehrenburg is the hand of my father, who, like the writer, was born in Kiev, 22 years after Ehrenburg, and who met the writer at his Moscow apartment in 1949, at the height of the “cosmopolitan” case, in which my father was one of the victims. Ehrenburg had returned from a 30-year exile nine years before their meeting. He had left the Russian Empire in 1908 and the Soviet Union in 1921. He did not return to the USSR until July 1940. He was not an emigrant: the writer had a Soviet passport, he was a correspondent for the Izvestia newspaper and visited the USSR six times – in 1924, 1926, 1932, 1934, 1935 and 1937.

Ilya Grigorievich Ehrenburg was born in Kiev on January 26, 1891, into a well-to-do Jewish family. His parents did not give him a Jewish education and spoke Yiddish only to hide unwanted information from their children. At the First Moscow Gymnasium, Ehrenburg encountered the antisemitism of his classmates: “In the gymnasium, my peers shouted ‘parched kike’ at me, they put pieces of pork lard on my notebooks.” He protested against tsarism. Ilya was expelled from the gymnasium for participation in the youth Bolshevik organization. In 1908 he was arrested for eight months, and in December Ilya immigrated to Paris, where he stopped revolutionary activities and in 1910 began to write poetry.

In Ehrenburg’s pre-Soviet poetry, Jewish motifs resound (To the Jewish People, collection I Live, 1911):

A people leading the lineage from Abraham,

Once a mighty and great nation,

You plowed the earth long and stubbornly,

Working the fields year after year.

Always humiliated, persecuted,

Under the heavy burden of your cares

You march on, barely tolerated,

A helpless and large people.

You’re not needed here, you’re a stranger and a persecuted one,

Take your slack-jawed children,

Go to your native fields of Jerusalem,

Where you knew the happiness of your youth…

The poet addressed his people in the collection Dandelions (1912):

Jews, it is impossible to live with you,

Alienating you, hating you,

In long and dreary wanderings.

I come to you every time.

World War I disrupted Ehrenburg’s literary life abroad. In 1917, he returned to Russia. There he was overtaken by the October Revolution, the leaders he criticized for “abominations.” In the fall of 1918, Ehrenburg moved to Kiev. Not realizing the complete victory of the Bolsheviks, October 22, 1919 Ehrenburg wrote a panegyric of Russia: “To love, to love by all means! And now I want to appeal to those Jews who, like me, have no other homeland but Russia, who have gotten all the good and all the bad from it, with an appeal to carry the lamps of love through these nights. The harder the love, the higher it is, and the more we all love our Russia, the sooner, washed in blood and tears, her holy, love-exuding heart will shine beneath the rubble.”

In November-December 1917, Ehrenburg wrote A Prayer for Russia:

May the golden sun rise,

Churches white, heads blue,

God-fearing Russia!

For Russia

Let us pray to God in peace.

The Jewish poet fully accepted “white churches” and Russian-Orthodox spirituality. Given Ehrenburg’s Jewish sentiments, it is clear that Prayer for Russia was a poetic self-indulgence and suggestion to others of his spiritual affinity with Russia.

Ehrenburg was answered in an open letter by the director and critic Samuel Margolin, who had also returned from Paris in 1917: “I know this love for Russia, which overwhelms the Jew both here on Russian soil and in foreign lands. Persecuted, without the right of residence, not admitted to a Russian school and a Russian university because of percentage restrictions, surviving pogroms in several generations, we are not tired of loving Russia. […] This is not our blessing, but our curse. […] The poet Ehrenburg has only one prayer for Russia and no other for a Jew. To what merger with a foreign culture should one live, to what stage should one scatter one’s spirit in a foreign land? […] In these days the Jew Ehrenburg forgets everything in the world except his love for Russia, love by all means, although this is from the psychology of the slave. […] Apparently, the assimilation of the Jewish intelligentsia has become slavery. […] We live on a staircase, not in a house, and I even think we live in a back alley among slouching and bent people – and that’s where our humble blessings and twisted psyche are born. […] Now I’m standing on the stairs. There are Jews near me. I have lived through the Bolsheviks’ desecration of the revolution, all the horror of the masses’ brutalization, all the oppression of the vengeance and rage of the divided groups of people. But the most painful, the most oppressive, the most bloody thing I experienced as a Jew. And that is why I think that it is a sin to kill the feeling of affinity with the Jews in one’s soul, and that for all Jewish intelligentsia an immutable life work has opened up – to think about the exodus of the Jewish masses. To where? I don’t know… But it is clear to me that the ladder is not a home, not a homeland. And I realized that it is necessary, absolutely necessary for a Jew to give all his strength, thoughts, feelings and actions, now, to the Jews.”

In the spring of 1918, Ehrenburg wrote: “The fate of Russia from the century to be enslaved by foreigners. You are now waiting for the Vikings [Bolsheviks], but did not the Vikings came to us now in sealed wagons. People who are strangers to Russia in spirit, who do not know and do not love Russia, are ruling. […] They came, they will go away, you will be left, Russia, humiliated, disgraced by this nice family”. In late October 1920, Ehrenburg was arrested by the Cheka and released thanks to the intervention of a high-ranking Bolshevik Nikolai Bukharin, his comrade at the gymnasium. Negatively perceiving the victory of the Bolsheviks, in March 1921 Ehrenburg again went abroad.

In 1921-1924, Ehrenburg, who lived in Berlin, did not notice the rampant antisemitism in Germany. Einstein, also living in Berlin at the time, was shocked by the murder of Walter Rathenau, committed on June 24, 1922, by three nationalists. One of them gave the reason for Rathenau’s murder at his trial: he is one of “the Elders of Zion.” Rathenau’s funeral was the most crowded in German history: two million people attended. Ehrenburg, who was in Berlin in 1921-1923, did not react to the rampant antisemitism in Germany. In Belgian cafes he wrote an ironic novel Julio Jurenito (1922) (A mixture of mockery and prophecy, the book savaged every ideology and religion while foreseeing both the Holocaust and Hiroshima) in 28 days. Ehrenburg writes, mocking everyone, including Lenin (chapter 27 of Julio’s meeting with the Grand Inquisitor, Lenin, omitted in Soviet editions of the novel). In a letter to Elizaveta Polonskaya dated June 12, 1923, Ehrenburg describes the “credit” he received for his satire: “We are Jews. We have taken a sip of the Parisian sky. We are poets. We know how to mock.” Ehrenburg lives and works freely in the “unfree” Europe he criticizes.

In 1940, Ehrenburg came to the USSR from occupied Paris. He returned to the country, where the repression of 1937 proved to him the cruelty of the authorities. The writer received frightening news from Izvestia in 1939: although he continued to be on the newspaper’s staff, his reports and articles would not be published. The USSR was changing its attitude toward Jews because of the Molotov-Ribbentrop Treaty. Stalin dismissed the Jew Maxim Litvinov as People’s Commissar of Foreign Affairs. Molotov, the new People’s Commissar, conducted “ethnic cleansing” in his institution and declared that “the synagogue was finished.” Ribbentrop was received in Moscow by Stalin and reported to Hitler that Stalin had promised to end “Jewish domination,” especially among the intelligentsia. “The complete and final construction of socialism” culminated in state antisemitism, which Stalin received from Hitler as an appendix to the agreement between Molotov and Ribbentrop. Shocked by this cooperation, Ehrenburg writes: “The shock was so strong that I fell ill with a disease incomprehensible to medics: for eight months I could not eat, lost about 20 kilograms. The suit hung on me, and I resembled a scarecrow. […] It happened suddenly: I read a newspaper, sat down to have lunch and suddenly felt that I couldn’t swallow a piece of bread.”

Ehrenburg saw Europe under the heel of the Nazis. He mobilized to fight the Nazis. On August 24, 1941, at a rally in Moscow, he declared: “I grew up in a Russian city, in Moscow. My mother tongue is Russian. I am a Russian writer. Now, like all Russians, I am defending my homeland. But the Nazis reminded me of another thing: my mother’s name was Hanoi. I am a Jew. I say it with pride. We are the people Hitler hates the most.” In the article Our Place (August 11, 1943), Ehrenburg wrote: “The Jews were not exterminated neither by the Pharaohs, nor by Rome, nor by the fanatics of the Inquisition. Hitler is not able to exterminate the Jews either, although history has not yet known such an attempt on the life of an entire people. […] Hitler brought to Poland and Byelorussia Jews from Paris, from Amsterdam, from Prague: professors, jewelers, musicians, old women, infants. They are put to death there every Sabbath, they are suffocated with gases, tasting the latest achievements of German chemistry. They are killed according to ritual, to the music of orchestras that play Kolnidre melodies.” In the article German Fascists Must Not Live (November 4, 1943), he begins his Black Book of Jewish victims of the Nazi genocide: “Who can imagine Ukrainian and Belorussian cities and towns without Jews? I saw this desert, these terrible ruins. Underneath them is a sea of blood. […[ There is not a single Jew in Ukraine anymore. The Germans have done their job.”

After the war, Ehrenburg created a new literature. different from that which was born in Paris. The glitter of the French capital was replaced by the heaviness of Gorky Street, where he lived and met my father, and the poverty of literary production. Soviet works came out from under his pen. He was already a Sistema writer and did not allow himself a Parisian front. The ironic writer faded, faded as an artist and became a servant of “socialist realism.” Bright ironic works were replaced by gray and leaden novels, one of which, Thaw, gave its name to the period of unfulfilled hopes. “New” Ehrenburg lost touch with the freedom of the Parisian sky, ceased to be a poet, ceased ridicule out of caution, and accepted the rules of the game on the Jewish question. In a letter to Stalin dated February 3, 1953, he reacted to a letter from academician Isaac Mintz, historian of the CPSU, and other Jews who agreed to the deportation of the people, to the editors of Pravda: “It seems to me that the only radical solution to the Jewish question in our socialist state is complete assimilation, the merging of people of Jewish origin with the peoples among whom they live. […] There is a definition of ‘Jewish people’ in the text which may encourage those Soviet citizens who have not yet realized that there is no Jewish nation.” According to Ehrenburg, “there is no Jewish nation.” All the peoples of the USSR had the right to their own culture, except for the Jewish people. The Jewish people, whose spirit was so close to Ehrenburg at the first, foreign stage of literary activity, was forgotten by him.

Translator Lilianna Lungina wrote in shock: “We did not understand how the author of Julio Jurenito an ironic book, […] a man in love with Paris, a fan of impressionism and abstract art, a cosmopolitan in the true sense of the word, could not only adapt to the Stalinist regime, but also serve it?” Lungina’s exclamation contains the answer to a bitter question: “A cosmopolitan in the real sense of the word,” Ilya Ehrenburg feared the charge of “cosmopolitanism” in 1949. Joshua Rubinstein, in the preface to the Russian edition of a book about Ehrenburg, wrote: “A Russian writer, a Soviet patriot and a Jew by nationality, Ilya Ehrenburg was for half a century one of the most enigmatic figures in the cultural life of the Soviet state.” Ehrenburg’s “enigma” consisted of a double life. He changed from anti-Soviet sentiments in the early years of Soviet power to loyalty to the “socialist motherland.” Repression and anti-Semitism provoked protest, which he tried to express and suppress. Love for Russia was replaced by love for the international USSR. He tossed himself between the USSR and Western Europe. He criticized the West and enjoyed life in it. He praised the USSR and dreaded living there.

After his early youthful poems of love for the Jewish people, after his deep solidarity with the Jews during the Holocaust,” Ehrenburg began to deny the existence of the Jewish nation, a third of which was exterminated by the Nazis, who also wished that the Jewish people did not exist. His negative attitude toward the existence of the Jews as a people served the Stalinist system, which borrowed the Nazi view that the Jewish people must disappear. In 1939, he was horrified when he learned of the cooperation of the Germans and Russians in the infamous Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact. He was not horrified when he colluded with the Soviets on the “non-existence” of the Jewish people.

*

Alex Gordon is professor emeritus of physics at the University of Haifa and at Oranim, the academic college of education, and the author of 10 books.