By Alex Gordon

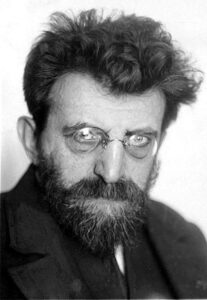

HAIFA, Israel — Erich Kurt Mühsam was born on April 6, 1878 in Berlin to a Jewish family. His father was a pharmacist in Lübeck, where the family moved when Erich was six weeks old. His parents were orthodox Jews. At school, Mühsam began writing poetry. At the age of 16, Erich was expelled from school for “socialist agitation.”

“I was an anarchist before I even knew what anarchism was. I became a socialist and a communist when I began to realize the injustices in the social structure,” he later wrote.

Following his father’s wishes, he becomes an apprentice pharmacist. However, the absent-minded Erich turns out to be a bad pharmacist. Shortly after his mother’s death, Mühsam moved to Berlin. During his student years, Erich moved away from Judaism and immersed himself in politics. In 1900 he joined the group New Society, where socialist philosophy prevailed and it was accepted to live in communes. Mühsam became a poet, playwright and a prominent member of the bohemians. He met fellow philosopher Gustav Landauer, who was eight years older than Erich. Mühsam called Landauer “one of the noblest minds of our time.” They became like-minded in anarchism, close lifelong friends, and many years later, colleagues in the government of the Bavarian Republic.

In 1904, Mühsam published his first collection of poems and began to make a name for himself as a writer of cabaret songs, jokes, and essays. His friend at the time, Rudolf Rocker, describes Mühsam as follows: “As a human being, Mühsam was one of the finest people I have met. He belonged to no party, which meant that the humanity in him was not destroyed as in so many others. He always behaved honorably and was a loyal and devoted friend. […] As a follower of Bakunin, Mühsam was a believer. His faith could roll mountains. He was a poet for whom there was no clear difference between the reality of life and his dreams.” Mühsam ignored the “reality of life” in which Bakunin’s antisemitism was evident.

In 1904, Mühsam left the New Society and settled in the artists’ commune Monte Verita in Ascona, Switzerland, where the principles of vegetarianism and communism were preached. Here he wrote his first play, The Rascals. At the same time, he began to collaborate in anarchist magazines, in connection with which he was under constant police surveillance and was arrested. In 1908, Mühsam moved to Munich. Augustin Sawhi, a Spanish anarchist, recalls: “Within a few years, he became well known in the artistic world of Munich for his carefree, witty lifestyle. […] Mühsam was considered the leader of Munich’s bohemians.”

In May 1908, Mühsam and Landauer founded the Socialist Union, whose purpose was “to unite all people convinced of the realization of socialism.” One member of this society perceived Mühsam as a “bohemian man” and Landauer as a “scientist” and “philosopher.” In 1911, Mühsam founded the newspaper Cain, which ran until 1914. He was the paper’s sole author and so defended pacifism, sexual freedom, and revolution. Mühsam led a promiscuous lifestyle but eventually married Crescenzia Elfinger, the daughter of a Bavarian innkeeper and hop grower, on September 15, 1915.

When World War I broke out, Mühsam refused to serve in the army and preached anti-war organizing. He was a remarkable orator. Actor and writer Fritz Erpenbeck wrote: “He was able to conquer the masses. […] He described events with such passion that it was felt that people believed him.” In April 1918, Mühsam was imprisoned for anti-war propaganda. He was released in November 1918 after the collapse of the German Empire.

On November 7, 1918, the Jewish leader of the Independent Socialists of Bavaria, Kurt Eisner, called for a general strike and, at the head of a large crowd in the parliament building, announced the establishment of a socialist republic in Bavaria, of which he became prime minister. His cabinet included the Jewish poet Ernst Toller, Mühsam and Landauer. In February 1919 Eisner was assassinated by a nationalist. He was replaced by Toller, but the latter resigned six days later.

The Bavarian Soviet Republic (BSR) was proclaimed, headed by the Jewish communist Eugen Leviné. Mühsam was one of the most popular personalities of the BSR; soldiers shouted his name and even carried him in their arms. He acted as a responsible politician, sought unity and compromise with the Communists, even appearing as their press attaché once or twice without sacrificing his utopian reformist ideas. In early May 1919 the republic fell, Landauer was lynched, Leviné was convicted and shot. Mühsam was arrested, and on July 12, 1919, he was convicted of treason and sentenced to 15 years in prison. In prison he joined the Communists, but left the Communist Party when he learned how the Bolsheviks were treating anarchists in Russia.

In prison, Mühsam wrote extensively. In 1923, he wrote a poem called The German Republican Anthem, where he attacks the judicial system of the Weimar Republic. He was frequently transferred to solitary confinement for writing “subversive” poems, for insulting a Bavarian minister, and for any minor infraction of the prison regime. On December 20, 1924, he was granted amnesty. The same amnesty was extended to Hitler, who served eight months of the five-year sentence he received for the Beer Putsch of 1923. It was Hitler and the Nazi Party leadership that became the targets of Mühsam’s satire. In 1930, he ended his last play with a call for revolution as the only way to prevent the Nazis from coming to power.

After the Nazi victory, Goebbels labeled Mühsam one of the nation’s chief enemies, one of the “ruiners of Germany.” On February 28, 1933, the morning after the Reichstag was set on fire, Mühsam was arrested. He was beaten, tortured and humiliated for 17 months. His wife Crescenzia (Cenzl) left a memoir of the last months of the poet’s life. She cites reports from eyewitnesses who sat with Mühsam in Brandenburg.

One of them writes: “I met Erich Mühsam in October 1933, while washing the stairs in the hallway. We had known each other since 1928, Mühsam trusted me. I told him that I would use everything to publicize his torment. To this he replied: ‘Don’t forget that thousands of unknown workers are subjected to the same torture in these walls. Don’t turn a public issue into a personal one.’ At this moment ‘buddy Tsakig,’ a guard who was particularly cruel, came up to us. With him was a Russian named Dmitriev, a member of the Russian Fascist organization in Berlin. He lived in Brandenburg under the guise of a prisoner. In reality, this “prisoner” had the authority to beat up anti-fascist prisoners. Before my eyes, the terrible beating of Mühsam began. They punched him in the stomach, kicked him, pulled his beard and hair. Then they made him lick dirty water with his tongue. They chased the exhausted Mühsam, drenched in blood, up and down four flights of stairs, with the guards whipping him with brooms and kicking him as hard as they could.”

At the end of 1933, Mühsam was transferred from the Brandenburg concentration camp to Oranienburg. On July 10, 1934, Cenzl was summoned to the police, where she learned of her husband’s death.

She wrote: “John Stone, an English citizen who lived for 35 years in Germany, writes: ‘On July 9, after the camp was taken over by guards, the famous poet and writer Erich Mühsam was murdered. The fate of this highly gifted man is a veritable chain of tortures that would shock humanity if they were all made public. This man was one of the finest and noblest men I have ever met. […] He knew that he would not come out of the concentration camp alive, but he held on with unparalleled willpower and firmly resisted the urge to commit suicide. On one of the last nights of his life he said to me, ‘If you hear that I killed myself, don’t believe it!'”

According to eyewitnesses, Cenzl wrote what happened a short time after the episode described, “In the restroom we saw Mühsam hanging. It was clear to all of us that a dead body had already been hung. The dead man’s face was calm, his tongue was not hanging out, his mouth was closed. The eyes were not out of their orbits, like those of a hangman. As far as we could see, there were no signs of new torture or wounds on the body. The rope had been tied very tightly – the kind of loop that could not have been made by an inexperienced Mühsam. We are convinced that Mühsam was sedated in the control room and then killed by poison injection. The corpse was probably carried across the courtyard to the restroom and hung there. The guards removed the body themselves. No commission was convened.”

Mühsam avoided the Jewish theme, as in the case of the silencing of the antisemitism of his idol Bakunin. Two cases were exceptions.

1.Like Trotsky, Mühsam was appalled by the Mendel Beilis case of ritual murder in Kiev. He wrote in 1913: “In Kiev, a poor Jew sits before a jury, forced to defend himself against the charge of ritual murder. Those who accuse him, headed by the Russian state prosecutor, declare that he killed a Christian boy in order to drink his blood with other Jews during a religious ritual. The accusation is made, although it has been known for hundreds of years that the idea of ‘ritual murder’ is mere prejudice. Nevertheless, even in Germany it finds its supporters, although it is crystal clear that the whole Beilis trial is nothing but a maneuver on the part of the “true Russians” to justify another pogrom. However, this hardly bothers anyone. People read about hordes of patriotic Russian Christians going from one Jewish home to another, torturing and killing dozens of Jews in the most heinous manner, not even sparing women and girls.”

Mühsam has no idea that the brutality shown toward him exceeds anything he has written about others. He continues, “People […] agree with antisemitic journals that claim Jews are turning the local Kiev case into a problem of international Jewry. […] Of course, the Beilis case is a problem for international Judaism, since the ridiculous charge of ritual murder bothers every Jew. The case must also be a problem for international Christianity. […] Everyone with Jewish blood in their veins knows that these accusations are not true; they know this with the same degree of certainty as if they were being accused! That is why, in moments like these, all who are Jews must remember our heritage and our community, and realize that the accusations made against Beilis are made against all of us. At times like these, the differences between orthodox and liberal, religious and secular, Sephardic and Ashkenazi, are irrelevant.”

In this passage, Mühsam sounds unsocialist. The situation of the Jews concerns him not in terms of class struggle, but as the grief and suffering of the people as such, manifested in pogroms and the ridiculous accusation of ritual murder against Jews.

Another of Mühsam’s remarks on the Jewish theme concerned a dispute over the predominant role of the Jews in the Bavarian Revolution while he was serving time for his active participation in it.

2. Mühsam wrote “One day I received a copy of the September 14, 1920, issue of a newspaper. […] There was a discussion there about how rich Jews should react to the ‘subversive revolutionary propaganda of Communists and Bolsheviks of Jewish origin.'”

“The discussion contained a letter written to the commerce advisor Sigmund Frenkel on April 6, 1919. At this point, the author hoped to discourage Jews from proclaiming a Bavarian Soviet Republic. […] When Frenkel took this letter to take it to the newspaper’s editorial office on the morning of April 7, the Red Guards stopped publication of the paper and sent the editors on vacation. Commerce Counselor Sigmund Frenkel, however, still believed that his text was important six months later. It was his Open Letter to Messrs. Erich Mühsam, Dr. Arnold Wadler, Dr. Otto Neurath, Ernst Toller and Gustav Landauer in the newspaper, which the author intended to benefit the Jewish community.

“According to the author of the letter, in the name of the Bavarian Jewish community, for the good of the Bavarian people, we must do nothing about this horror, chaos and misery of this nation, which is also the future of this country. The Bavarians themselves, and no one else, are responsible. […] I sent him the following reply on September 24 [1920] from the Ansbach fortress, where I was imprisoned:

“‘I am a Jew and will remain one as long as I live. I have never denied being a Jew, never officially abandoned the religious Jewish community. […] I see neither dignity nor disadvantage in belonging to Jewishness. It’s just part of who I am, like my red beard, my weight and my personal interests. […] Let us discuss only this: should Jews, as a minority, despised in many ways, refrain from political commitment and activity in the name of solidarity with their fellow tribesmen, at least until these commitments and activities are officially endorsed? […] I am surprised that a respected commerce counselor uses the word “outsider” for his attempt to deny our right to participate in the social liberation of the people. Indeed, I don’t know exactly whom you call an ‘outsider”: every European Jew or only non-Bavarian Jews in Bavaria? […] But how does this correspond to the notion of an indivisible Germanness, a feeling that has embraced all German Jews since at least 1914? During the war, even the Jews shouted the antisemitic slogan: “Germany, Germany above all” and were united, […] at least until the end of the disastrous war. […]

“‘Is not the accusation of foreignness made only in connection with the expression of controversial political views? […] But let us cast a glance at those whom you call outsiders: Landauer (whose murder does not seem justified even for you to bring your accusation, even after 17 months) was from Karlsruhe, I am from Lübeck, but we lived in Munich for 12 years, and I am married to the daughter of a Catholic peasant from Lower Bavaria, Wadler is a native of Munich. Perhaps in agreement with the antisemites, you see every single Jew as an outsider? […] You will never understand why we reject your insistence that our plans are “sinister and contrary to human nature,” that our path is doomed to lead to “chaos, destruction and devastation,” and that our ideas will cause famine in Southern Bavaria. […] All your arguments show me that you can only assess the well-being of the world from the capitalist’s point of view. You are fully convinced that you are right […] when you claim that “the differences between rich and poor will never disappear”. […]

“‘Finally, let me ask you, what are we discussing here, a “Jewish” problem or a human, socio-ethical and international problem? I do not agree with your logic, according to which the world revolution, the liberation from untold poverty caused by a war unleashed in the interests of world imperialism, requires different deeds from us Jews and from other peoples. […] I believe that Jewry is honored that the daily attacks of the antisemites are not limited to attacks on Jewish extortionists and profiteers, but also include the persecution of idealists and martyrs such as Rosa Luxemburg, Leo Jogihues, Gustav Landauer and Eugen Leviné. This is what I had to say to a commercial counselor who sees it as his duty to protect Jewry from its degenerate sons.'”

Mühsam did not realize that such a revolutionary performance by the Jewish Socialists would hit all Jews. In Bavaria and in Germany in general, many people, including future Nazis, called the leaders of the BSR “outsiders.” Thomas Mann, believed that the revolutionary ideas heard in Munich were alien, not German. Mühsam and his comrades were feared not only by wealthy Jews such as Frenkel, but also by the “progressive” German intelligentsia, not to mention the leaders of the Nazi Party, which had just been established in Munich.

*

Alex Gordon is professor emeritus of physics at the University of Haifa and at Oranim, the academic college of education, and the author of 10 books.