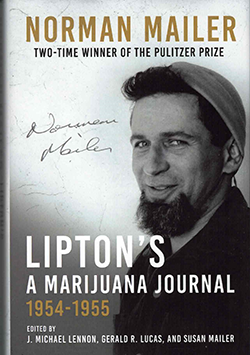

Lipton’s: A Marijuana Journal, 1954-1955 by Norman Mailer; edited by J. Michael Lennon, Gerald R. Lucas, and Susan Mailer; New York: Arcade Publishing; © 2024; ISBN 9781956-763874; 316 pages plus endnotes and index; $32.99.

Corrected and updated June 18.

SAN DIEGO – Smoking marijuana being illegal at the time (1954-1955), author Norman Mailer referred to the weed he smoked regularly by the euphemism “Lipton’s,” a popular brand of tea. “Tea” was another euphemism for marijuana. Smoking marijuana helped him to go into reveries. He would write in his journal the thoughts that came to him under its influence. Sometimes, he would be so pumped up, he took Seconal to be able to fall back asleep.

SAN DIEGO – Smoking marijuana being illegal at the time (1954-1955), author Norman Mailer referred to the weed he smoked regularly by the euphemism “Lipton’s,” a popular brand of tea. “Tea” was another euphemism for marijuana. Smoking marijuana helped him to go into reveries. He would write in his journal the thoughts that came to him under its influence. Sometimes, he would be so pumped up, he took Seconal to be able to fall back asleep.

In his journal, he would number his reveries, which sometimes ran a short sentence and at other times filled several pages. Favorite topics were fornication, which he discussed with an alternative and favorite “f” word; the difference between saints and psychopaths, elements of both he believed his personality encompassed; semantics; his bisexuality; and perhaps most pervasive throughout the journal, his belief that society conspires to erase a person’s unique individuality and must be resisted.

While he ponders those subjects deeply, he rarely reflects on his Jewish identity. Jewishness appears to be an accepted, yet unfortunate, given in his life, a subject less exciting to his marijuana-enhanced worldview than even that of the similarity of sounds in the English language and how one word may relate to another on a deeper level.

Nevertheless, Mailer makes sufficient reference to his Jewishness that we understand why in The Naked and the Dead, his debut novel, that a pair of Jews [Goldstein and Roth] serving together in World War II form a bond amid the antisemitism of other soldiers in their unit.

Early in his journal, Mailer, then in his early 30s, describes himself as “an over-friendly anxious boyish Jewish intellectual,” and more than 150 pages later as “the sweet, clumsy anxious to please middle class Jewish boy.”

One day, as he looked at himself in the mirror, “high on Lipton’s, I saw myself as follows: the left side of my face is comparatively heavy, sensual, possessor of hard masculine knowledge, strong, proud and vain. Seen front-face, I appear nervous, irresolute, tender anxious, vulnerable, earnest and Jewish middle class. The right side of my face is boyish, saintly, bisexual, psychopathic, and suggests the victim.”

Discussions of his Jewish identity almost always devolve into self-deprecation. He quotes his first mother-in-law, Jenny Silverman, of describing him as “the little pisherke with the big ideas.” Pisherke is a variant of pisher, Yiddish for a “nobody.”

He makes himself out to be what later would become a Woody Allen caricature.

He discloses that his family name wasn’t originally “Mailer,” but something else in Russian or Yiddish with a remote resemblance to that name, adding that “there is nothing in the world like being a false Englishman.”

The Jewish psychologist and novelist Robert Lindner, author of Rebel Without a Cause, was a close friend to whom Mailer sent carbon copies of his journal periodically, inviting comment. Their correspondence indicates some knowledge of the mamaloshen. On June 12, 1954, Mailer wrote to Lindner, “Amigo, I’m afraid we’re a couple of alta kakes.” Lindner, in a subsequent letter to Mailer, wrote that a publisher rejected his collection of psychoanalytic tales in The Fifty-Minute Hour because of a feeling that “it was not quite kosher.”

Mailer confided to his journal that Lindner is “one of the few people I don’t feel competitive toward. I feel we could have a Marx and Engels relation and leave the matter of who’s Marx aside until we both have grown.”

From an ethno-religious standpoint, the analogy may have been deficient. Engels was a Calvinist. Like the two Communist theorists, Lindner and Mailer helped each other advance inchoate thoughts into well-written words.

*

Donald H. Harrison is publisher and editor of San Diego Jewish World.