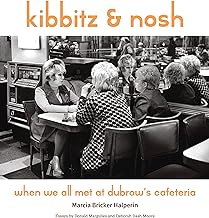

Kibbitz & Nosh by Marcia Bricker Halperin; Ithaca, New York: Cornell University Press, (c) 2023; ISBN 9781501-766510; $27.54 on Amazon

By Eva Trieger

RAMONA, California –There is no doubt in my mind that a picture is worth 1,000 words. And when we’re talking about photographs of an era where Jews made up over 50% of the population of Brooklyn, that’s a lot of yentas schmoozing and rattling a tea cup!

RAMONA, California –There is no doubt in my mind that a picture is worth 1,000 words. And when we’re talking about photographs of an era where Jews made up over 50% of the population of Brooklyn, that’s a lot of yentas schmoozing and rattling a tea cup!

Marcia Bricker Halperin invites us into the heyday of the New York institution, the cafeteria. In her photographic extravaganza, Halperin exposes the myriad faces and characters, who comprised the patrons of the iconic Dubrow’s cafeteria.

History, culture and gastronomy collide in this collection of photographs that depicts the American Jewish palate, fashion and routines of Brooklynites from 1970 to 1985. As an art major of Brooklyn College Halperin sought out subjects for her medium. She landed on Dubrow’s cafeteria as a spot to hone her skill. Though it was in her own Flatbush neighborhood, she’d never been inside.

Initially, she snapped candid photos, capturing “ex-vaudeville performers, taxi drivers, Holocaust survivors, ex-prizefighters and bookies. Women named Gertrude, Rose and Lillian all had sad love stories to tell and big hearts.” These encounters are captured for eternity in black and white and were developed in the photographers’ family’s apartment kitchen sink.

Dubrow’s cafeteria was brought into being by George Dubrow in 1952. His vision established a Jewish cultural center that tolerated other ethnic groups but understood its role as a gathering spot for Brooklyn’s burgeoning Jewish population. Post WWII gustatory demands broke down the laws of kashrut. The new menu took into account the newfound Jewish fascination with Chinese food. Chicken chow mein, shellfish and other treyf dishes attracted diners by the score. The spot was a gathering place for the neighborhood, businessmen, families and even date nights.

The images in the book tell a much larger story beyond the meteoric rise of Dubrow’s Cafeteria. The 136-page collection portrays an era of hope, prosperity, acceptance and self-discovery for Jewish New York. With essays by playwright Donald Margulies and historian Deborah Dash Moore, the reader is invited to step back into this bygone era of the Jewish-American experience. The writer takes us from the history of Jews moving up the socio-economic ladder and eventually leaving the city in favor of the suburbs.

Dubrow’s cafeteria was distinct from the ubiquitous New York delicatessens. The cafeteria did not rely on waiters. Patrons could sit and schmooze over a cup of coffee for hours on end or purchase complete meals of reasonably priced Jewish comfort foods. The menu featured kugel, Danish, three types of herring, and cheesecake. Halperin recalled a lecture she’d attended in 1977 where author Isaac Bashevis Singer spoke. Singer often used cafeterias as the backdrop for his short stories. This lent an air of a mission to her research. She wrote that she felt that she was privy to the inside scoop of a “vanishing world.”

It wasn’t only Jews who found their way into Dubrow’s. During his 1960 presidential campaign, John F. Kennedy visited Dubrow’s. The staff who’d witnessed this visit, regaled the photographer with tales of the auspicious day.

The success of the original King’s Highway location led to the installation of another in Brooklyn on Eastern Parkway, and a third in Manhattan’s garment district. Though the original in Flatbush shuttered its doors in 1978, the Manhattan cafeteria managed to hang on until 1985. This third iteration was generally filled with garment workers and tourists, not the same “guys and dolls” crowd who frequented the older Brooklyn sibling. Those “Runyonesque” characters socialized as if Dubrow’s in Flatbush was a social club where they smoked cigars, made book, and read the Yiddish Forward.

Turning the pages of these black and white pictures I almost had the sense I was seeing my own relatives kibbitzing over some strudel and a cuppa. While I never set foot in a Dubrow’s I have vivid memories of Jahn’s ice cream parlor in the Bronx. Achieving not-quite world renown for their Kitchen Sink sundae, which was intended to be shared by eight diners, the place was iconic. But just like Dubrow’s the change in demographics, palates and urban landscape has edged all but one of the chain into obscurity. Still, I remember walking past all my landsmen on the Concourse, reading their Yiddish papers, Nanas pushing prams while cooing to their tatalas and enjoying the ease and comfort of their Jewish New York niche.

*

Eva Trieger is a freelance writer specializing in coverage of the arts.

Thanks so much for commenting and sharing your memories of these New York institutions!

My Dubrow’s was Kings Highway a few blocks away from my friends father’s pizzeria called the Bella Donna Pizzeria, And my Jahns was on Nostrand Ave.