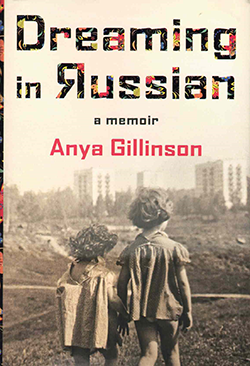

Dreaming in Russian: A Memoir by Anya Gillinson; New York: Skyhorse Publishing © 2024; ISBN 9781510-782129l; 278 pages; $28.88.

SAN DIEGO – Memoirs are typically written by famous people or by those who survived extraordinary events. Politicians, movie stars, artists, and diplomats are in the first category. Soldiers and Holocaust Survivors are in the second. But who is Anya Gillinson? How many people outside of New York City have ever heard her name? What impelled her to write her memoir?

SAN DIEGO – Memoirs are typically written by famous people or by those who survived extraordinary events. Politicians, movie stars, artists, and diplomats are in the first category. Soldiers and Holocaust Survivors are in the second. But who is Anya Gillinson? How many people outside of New York City have ever heard her name? What impelled her to write her memoir?

Gillinson was the granddaughter of a renowned Jewish surgeon and a well-known Russian chanteuse. Her parents were also Moscow celebrities, her father was a doctor, and her mother was a concert pianist. She grew up in a prestigious Moscow neighborhood where one might ride up in an elevator with Leonid Brezhnev or bump into Mikhail Gorbachev.

Her parents traveled to New York, where her father was murdered while shielding her mother during a street robbery. She and her sister were children when their mother came home from New York and told them the horrible news. During the criminal trial, their mother had to return to New York to testify, and that period saw the solidification of a relationship with another Soviet-born Jewish doctor, a former Refusenik, who invited the family to immigrate to the U.S. and live with him.

Speaking no English, the family was dependent upon him, but after a while her mother and he grew apart and the mother moved on to a new lover. Meanwhile, Gillinson went to college with the hope of going to medical school, while her sister continued to study ballet. Gillinson adjusted well to the United States, but her sister missed Russia. She returned to Moscow, where eventually she was admitted to the corps of the Bolshoi Ballet.

The memoir takes us through Gillinson’s love affairs and marriages, her reluctant turning from a career in medicine to one in law, and eventually to her marriage to Sir Clive Gillinson, the British executive and artistic director of Carnegie Hall. The marriage returned Anya to the privileged “insider” observer role in the arts world—similar to what she had enjoyed in Russia as the granddaughter of a celebrated chanteuse and daughter of a concert pianist.

These steps along her life’s journey enabled her to essay a comparison of life and cultural norms in the Soviet Union versus those of the United States; paint fascinating portraits of relatives and lovers who occupied her life and that of her mother; and inveigh against feminism. She believes the man should be treated by his family like a king and so long as the man protects and provides for his family, a woman and children should happily be subservient to him.

One can disagree with that particular view, and still enjoy reading other long, beautiful, and thoughtful passages of this memoir. If Gillinson had written the same story about someone else, her work would merit consideration as a successful novel.

*

Donald H. Harrison is publisher and editor of San Diego Jewish World.