By Jerry Klinger

BETHEL, New York — Not many people know much about Max Yasgur. Perhaps some, and I am one of them, knew of him only because I was at the beautiful Bethel Woods Center for the Arts on August 17, the 55th anniversary of Woodstock. The Center is located on Max’s former farm site in Bethel, N.Y. I came to Bethel to dedicate the eighth marker in the Borscht Belt Historical Marker Project system that JASHP was funding later that day.

BETHEL, New York — Not many people know much about Max Yasgur. Perhaps some, and I am one of them, knew of him only because I was at the beautiful Bethel Woods Center for the Arts on August 17, the 55th anniversary of Woodstock. The Center is located on Max’s former farm site in Bethel, N.Y. I came to Bethel to dedicate the eighth marker in the Borscht Belt Historical Marker Project system that JASHP was funding later that day.

That day, at both sites, the clock was pushed back to when youth was changing, and America was a vision of promise.

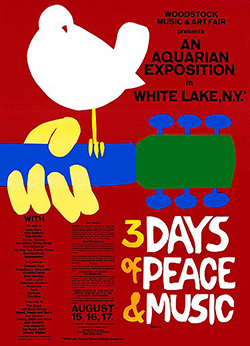

Woodstock, the iconic “Hippie” counter-culture music festival, was celebrated by ~460,000 baby boomers from August 15 to 18, 1969. The “happening” was on the rolling hills of Max Yasgur’s Dairy farm in Bethel, N.Y. It almost never came about.

The four Jews who organized the Woodstock Festival, Michael Lang, Artie Kornfeld, John Roberts, and Joel Rosenman, were repeatedly unable, more like refused, siting permission until Lang connected with Jewish Dairy Farmer Max Yasgur. No one wanted their communities to be overrun by the free-love, pot-smoking, anti-establishment, tie-dyed, disaffected youth of the anti-Vietnam war generation.

Yasgur ran the largest dairy farm in Sullivan County, New York. 1969 had been a very wet summer. It was impossible for Yasgur to grow sufficient hay to tide his herds over winter. He would have to purchase additional hay on the open market. It would be a heavy economic burden.

When Lang met Yasgur, the two men were worlds apart in perspectives. Lang, 25, sported the full bushy-haired look of the counterculture. Lang’s cultural antithesis was Yasgur, lanky, hands callused from farming, hair short-cropped, a World War II vet, large-framed black glasses, white shirt, and socks. Yasgur was a conservative, conservative Republican who supported the Vietnam War.

It was a business meeting. Lang needed Yasgur for a venue to host his music event. Yasgur needed Lang to provide a source of revenue to buy hay for his cows. They came to a financial agreement for an estimated 50,000 attendees and a three-day festival.

The town of Bethel and much of Sullivan County wanted nothing of either of them when the news came out.

There are many tales about why Max agreed to the Woodstock Festival. Sifting through the detritus of imagination and semi-journalistic reportage, the best why was written by Sam Yasgur, Max’s son in his book, The Woodstock Festival’s Famous Farmer.

Max Yasgur drove into White Lake, confronting the local town board, which was contemplating an ordinance making the Music festival impossible in Bethel.

“I hear you are considering changing the zoning law to prevent the festival. I hear you don’t like the look of the kids who are working at the site. I hear you don’t like their lifestyle. I hear you don’t like they are against the war and that they say so very loudly.” According to the reports, one of the men in the room said that was right and that he and some others intended to see to it that no long-haired, draft dodging, anti-war hippies were going to come into their town. Dad’s retort was clear and direct. “I don’t particularly like the looks of some of those kids either. I don’t particularly like their lifestyle, especially the drugs and free love. And I don’t like what some of them are saying about our government. However, if I know my American history, tens of thousands of Americans in uniform gave their lives in war after war just so those kids would have the freedom to do exactly what they are doing. That’s what this Country is all about and I am not going to let you throw them out of our Town just because you don’t like their dress or their hair or the way they live or what they believe. This is America and they are going to have their festival.”

The reporters all confirm that there was a distinct silence when he finished.

After a perfectly timed pause, Dad added the knock-out punch, facing those few men directly for something that had long rankled him about them. “What are you planning to do next? Are you going to try to throw me out of Town because I am a Jew?”

The Festival got its permit.

On the third day of the Festival, Max Yasgur stood on the stage just before Joe Cocker came out to do his set. A million eyes stared back at him as he said:

“I’m a farmer. I don’t know how to speak to twenty people at one time, let alone a crowd like this. But I think you people have proven something to the world — not only to the Town of Bethel, or Sullivan County, or New York State; you’ve proven something to the world. This is the largest group of people ever assembled in one place. We have had no idea that there would be this size group, and because of that you’ve had quite a few inconveniences as far as water, food, and so forth. Your producers have done a mammoth job to see that you’re taken care of… they’d enjoy a vote of thanks. But above that, the important thing that you’ve proven to the world is that a half a million kids — and I call you kids because I have children that are older than you are — a half million young people can get together and have three days of fun and music and have nothing but fun and music, and I – God bless you for it!”

An incredible cheer rose for Max afterward.

Max paid a price for standing up for his conservative values. He was sued and shunned by neighbors. His health continued to deteriorate. Heart disease was an issue. He sold his farm and retired to his winter home in Marathon, Florida. He died of a heart attack in 1973. Max was 53 years old.

The Woodstock Festival was a financial disaster for the promoters. Ultimately, they recouped their money through mass media, marketing, and the famous documentary about Woodstock. Yasgur was offered a piece of the successful film. True to his values, he took none of the money for himself, preferring to donate it all to drug rehab centers.

The Bethel Borscht Belt marker dedication was a big success. Elliot Landry, the official photographer of the Woodstock Festival, was one of the speakers. He shared the vision of the Woodstock days.

The world was moving from the Piscean Era, astrologically ending about 2100 A.D. The Age of Aquarius would follow it, he explained. The Piscean Era, a period flawed by autocratic rule and control by centralized government, telling us what, when, and how we were to live our lives, was ending. The Age of Aquarius was coming when the inner good of people would enable all humanity to live peacefully and freely. We would no longer have imposed rules controlling us.

Landry had described the utopian ideals of Woodstock. It is still being strived for.

*

Jerry Klinger is the President of the Jewish American Society for Historic Preservation