By Alex Gordon

HAIFA, Israel — The emancipation of Jews in Austria-Hungary was a fait accompli from the 1860s and 1870s, but it did not abolish popular and Catholic antisemitism. Judophobia posed an obstacle for Jews, but it was also a challenge: the further entrenchment and consolidation of Jewish status required secular education, by which they entered the circle of the liberal bourgeoisie.

In essence, Jews exercised auto-emancipation through education. The thirst for knowledge was derived from the Jewish religion and was a response to centuries of disenfranchisement. In Talmudic classes, young Jews learned to think abstractly, pose incisive questions, think critically, interpret, debate, and ponder various possibilities. Practicing the Jewish religion was a serious mental exercise, giving those Jews who switched to other areas of knowledge the skills of analysis, debate, and the ability to learn.

Prague-born Jewish philosopher Hans Kohn argued that Jewish parents of his time (1891 – 1971) strove to give “the best education to their children, which was characteristic of them and indicated their respect for learning.” The rapid growth of Jewish education, wealth and prosperity seemed a challenge and alarmed the thinking members of the nation.

According to Jacob Wasserman (1873 – 1934), a German writer of Jewish origin, Vienna was at the turn of the century a city where “all public life was in the hands of the Jews. Banks. The press, the theater, literature, social organizations – all these were in the hands of the Jews. […] I was amazed at how many Jews there were among the doctors, lawyers, clubgoers, snobs, dandies, proletarians, actors, newspaper men, and poets.” Indeed, among financiers the proportion of Jews was 71%, among lawyers 65% of Jews, among doctors 59%, and among Viennese journalists Jews made up half.

There was no political consensus in Vienna about what was allowed and forbidden to say about Jews. Proof of this was the Jewish writer Hugo Bettauer’s 1922 dystopia The City Without Jews: A Novel of the Day After Tomorrow, which sought to show how absurd it would be to evict the Jews from Vienna.

Austrian Jews made an enormous intellectual contribution to Vienna: the composers Mahler and Schoenberg, the writers Schnitzler, Hofmannsthal and Stefan Zweig, the philosopher Wittgenstein, the psychologists Freud and Weininger. The Viennese Jews’ views on the Jewish question were typical of the liberals. Vienna’s Jewish liberals demanded a change of attitude toward the Jews in accordance with the “demands of progress.” But the pace of Austrian “progress,” cooled by rising nationalism and strengthening National Socialism, was slow.

The Jews were in favor of liberalism, for it gave them equal rights before the law. Their assimilation into Christian society was apparently an irresistible temptation to them, for it seemed a vital solution to the Jewish question.

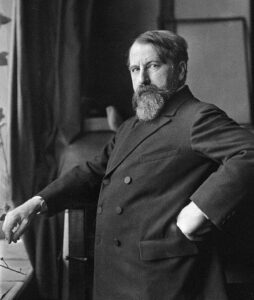

In his novel The Road to Freedom (Der Weg ins Freie 1908), the Austrian Jewish writer Arthur Schnitzler (1862-1931) composed a conversation between two enlightened Viennese Jews. One bitterly says to the other, “Who created the liberal movement in Austria? The Jews. Who betrayed and abandoned the Jews? The liberals. Who created the German nationalist movement in Austria? Jews. Who abandoned the Jews in their distress, and in fact, despised them like dogs? The German nationalists. The Socialists and Communists will do the same. As soon as dinner is served, they will all immediately drive you from the table.”

Schnitzler was born into a well-to-do Jewish family. The son of a prominent Viennese laryngologist, he studied medicine at the University of Vienna from 1879 to 1884, practiced from 1886 to 1893, but then turned his full attention to literature and theater. He was interested in the psychoanalytic theory of Sigmund Freud and the Zionist teachings of Theodor Herzl, and was well acquainted with both authors. From 1923 he was president of the Austrian PEN club. His father, Johann Schnitzler, a baptized Jew, was a well-known physician.

Schnitzler graduated in medicine from the University of Vienna and practiced for a number of years as a psychoanalyst in collaboration with Freud. Already a well-known writer, Schnitzler continued his scientific activities, publishing works on such subjects as hysteria, hypnosis, and sexopathology.

There is hardly another modernist author who turned to medical themes with the same consistency as Schnitzler. But hardly any other writer was as much surrounded by medicine in his family as he was. As noted, his father was a famous laryngologist. His mother came from the family of a prominent physician. Serious success in the medical field were achieved by a brother and son-in-law.

For Schnitzler, this circumstance served as a constant challenge and the subject of internal discord because of the fact that he had no real interest in his chosen profession by virtue of family tradition. At the same time, he was in no hurry to leave this activity. After receiving his M.D. degree, he assisted his father in the clinic for several years and served as editor of his father’s journal, the Internationale Klinische Rundschau (International Clinical Review). There he published an article on the treatment of functional aphonia (loss of voice) by hypnosis and a number of reviews, including on Sigmund Freud’s translations from the French of the works of Charcot and Berngheim.

In 1913, Freud’s disciple, the Austrian-American psychologist of Jewish origin Theodor Reik published the book Arthur Schnitzler as a Psychologist (1913), in which he analyzed the behavior of the characters in the writer’s works, as if they were real cases from his medical practice. The vulnerability of this approach was noted by the writer Robert Musil: “To treat the characters of a work of fiction as living human beings is to be as naive as a monkey grasping a mirror reflection.”

Schnitzler, although he admitted that in the early period of his work “case” interested him more than a person, still could not accept the view of his works as stories of illness. A telling difference also lies in the fact that Schnitzler’s short stories do not end with a “cure.” He did not consider it possible to include the demonstration of therapeutic talents in his artistic strategy. “Although his skepticism was more radical than Freudian, as a professional physician, Schnitzler, explored in his literary work the problems of the psyche, stubbornly maintaining the role of a passive “diagnostician”.

Freud called Schnitzler his “double” in a letter addressed to him. In the preface to the proceedings of the conference devoted to the 140th anniversary of the Austrian writer, it was emphasized that Schnitzler was a great diagnostician of the Austrian soul and Austrian politics. His compatriot, the writer Jean Amery (Hans-Haim Mayer), said that “Kakania (a designation of Austria-Hungary, German for kaiserlich und königlich, imperial and royal) had no more energetic and conscientious critic and no more understanding friend than Arthur Schnitzler […]. The clarity of his mind allowed Schnitzler to see the world and Austria more deeply than the deep thinking of Musil and the fiery anger of Karl Kraus.”

Jewish issues occupied an important place in the worldview and work of Schnitzler; in the mid-1880s, he was interested in discussing with Herzl the ideas of Zionism, but treated them critically. The novel The Road to Freedom reflected the writer’s attachment to the spiritual and historical values of the Jewish people and his deep understanding of the painful complexes arising in the soul of the emancipated Jew. Schnitzler shows that the main cause of these complexes is the unsuccessful desire to forget about his nationality, to “dissolve” in the social environment.

The writer Jacob Wasserman recognized himself in the character of the writer Heinrich Berman. The author of the novel looks at the Jews through the eyes of his protagonist, the composer Georg von Wergenthin-Recco: “For the first time, the word ‘Jew,’ which he used to pronounce mockingly, lips curling contemptuously, began to appear as full of a whole new dark meaning. It was a premonition of the tragic fate of this people, which in one way or another manifested itself in everyone, both in those who lived in its midst and in those trying to escape beyond its borders. Both experienced their origins as a shame, a trauma, or a legend that does not concern them, but both listened to those who persistently called for a return to it as a destiny, an honor, or an immutable fact of history.”

In the salon of the banker Ehrenberg, Jewish intellectuals engage in controversial discussions about the future. The paths to that future are Zionism, socialism, and assimilation into the dominant Viennese society. the reader learns much about the origins, insults, and denigration of Jews in the multi-ethnic state of Austria-Hungary. The love of the Jews for their homeland is discussed. Jews renounce their faith and even become antisemitic.

Schnitzler believed that antisemitism was an indispensable aspect of Jews as a national minority in any country. He did not see either Zionism or assimilation as a solution to the problem. In Schnitzler’s opinion, every Jew must overcome his or her own self-alienation complexes on an existential level, determine the way of his or her national identification and the form of relations with the world around him or her. Schnitzler did not try to solve the Jewish problem; he was only a passive diagnostician giving a recommendation-recipe for the Jew’s self-healing.

*

Alex Gordon is professor emeritus of physics at the University of Haifa and at Oranim, the academic college of education, and the author of 10 books.