By Alex Gordon

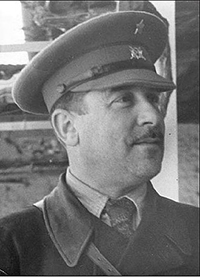

HAIFA, Israel — On June 11, 1937, the Hungarian-born commander of the 12th International Brigade, General Paul Lukacs, the hero of two of Hemingway’s works, the novel For Whom the Bell Tolls and the play Spain, was killed in a bombing raid on a highway near the Spanish town of Huesca. His remains were transported to Hungary. Spain declared national mourning on the day of General Lukács’ funeral, and the general himself became a Spanish national hero. General Lukács was a writer, who wrote under the pseudonym Máté Zalka in Hungarian and Russian. He was a communist, red commander, hero of two civil wars – in Russia and in Spain. His real name was Béla Frankl, and he was a Jew.

Máté Zalka was born in 1896 in the village of Matolcs in the family of a wine shop (tavern) owner Mihály Frankl and his wife, who had nine children. After graduating from a commercial school in Mátészalka (hence his pseudonym), he volunteered for the Austro-Hungarian army. As a junior officer (lieutenant) in the Hungarian Hussars, he participated in the battles of the First World War. In 1916, Máté Zalka was taken prisoner in Russia. Passion for political radicalism, inherent in some part of the Jewish intelligentsia in Hungary in those years, determined Zalka’s path.

He was an organizer of the Hungarian Red Guard detachment in Khabarovsk (1918), and later became a member of the Communist Party, fought on the fronts of the Russian Civil War, participated in the peasant uprisings in the rear of the White Army Kolchak, and, in 1919, a fighter of the eighteen thousandth Siberian partisan army and the Chapaev’s division, who successfully transported the famous echelon with gold to Moscow. For the “golden echelon” Lenin gave Máté Zalka a dagger with a golden handle and a saber with a golden hilt.

Later, Zalka served as a commander of a regiment of the Red Army (1920), a participant in the battles at Perekop and against Makhno (1921-1923). In 1920, he joined the Soviet Communist Party. From 1928 he worked in the staff of the CPSU Central Committee and in the bureau of the international association of revolutionary writers and wrote books.

One of the leaders of the 1919 Hungarian Soviet Republic and the organizer of the Red Terror in Crimea in 1920, another Hungarian Jew, Béla Kun, a Communist loyal to Soviet power, was executed by Stalin in 1938. Like Béla Frankl-Máté Zalka, Béla Kun, a member of the Austro-Hungarian army, was taken into Russian captivity in 1916. Kun’s bloody deeds are well known, but they did not save him from execution by Stalin. Was Máté Zalka an executioner and punisher during the Russian Civil War? After the collapse of the USSR, the secret archives of the Red Army began to open, from which it became known that the Hungarian detachment organized by Máté Zalka in Khabarovsk participated in punitive operations in Siberia and stood out for its outstanding cruelty among other units of the Red Army.

In 1918, with its atrocities Zalka’s detachment was not inferior to the opposing units of Ataman Grigory Semenov, a lieutenant general of the White Army. Semenov was arrested in New York in 1921 on charges of embezzlement of materials and funds belonging to a Russian company, and spent six days in a federal prison in New York, and was released on $25,000 bail. At the same time, a report on the Japanese occupation of Siberia, Ataman Semenov’s actions and his connections with the Japanese military command was presented at a U.S. Senate hearing.

General William Sidney Graves, commander of the American Expeditionary Force in the Far East and Siberia during the Russian Civil War, and his deputy, Colonel Charles Morrow, speaking to senators, stated that “Semenov was responsible for the extermination of entire villages, unleashing a deliberate campaign of murder, rape and pillage that cost the lives of 100,000 men, women and children.” It turned out that in 1921, when he fought against the detachments of Nestor Makhno and other atamans in Ukraine, he did so while serving in punitive units of the All-Russian Extraordinary Commission and the Main Political Directorate (both names identify special-purpose units of the Soviet secret security services).

Because the Ataman movement enjoyed widespread support from the local population, many of Zalka’s actions resulted in punitive operations against civilians. Zalka was an executioner on a much smaller scale than Kun. Unlike his tribesman and Hungarian compatriot, he was an experienced military man and an adventurer. He suffered a different fate than Kun. He left the USSR and became a Spanish general.

The participation of foreigners in the Spanish Civil War was an interference in the internal affairs of another country. Therefore, General Lukács’ real name and nationality were concealed for some time. However, it was important for the Soviet government to publicize this secret in order to show its great role in the fight against fascism. The secret of Máté Zalka’s Jewish origin was kept much longer than the secret of General Lukács’ origin.

Before his death, he managed to write his novel Doberdo about the First World War, which centers on one of the bloodiest battles of that war, held near the Italian village of Doberdo. Zalka critically describes the absurdity of warfare and unequivocally condemns the perpetrators of the world war. Criticizing and condemning the “imperialist” war, Zalka called for a Civil War. Having actively participated in two civil wars, he called for a new civil war as a method of winning communism, knowing from his extensive Soviet and Spanish experience the atrocities of civil wars.

Zalka saw in socialism and internationalism the solution to the Jewish question. In a paroxysm of internationalism, he became the hero of three peoples, Hungarian, Russian and Spanish. He did not become the hero of the Jewish people.

*

Alex Gordon is professor emeritus of physics at the University of Haifa and at Oranim, the academic college of education, and the author of 10 books.