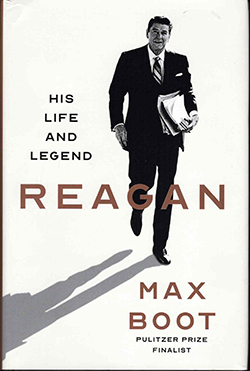

Reagan: His Life and Legend by Max Boot; New York: Liveright Publishing Corporation; (c) 2024; ISBN 9780871-409447; 836 pages including notes, bibliography, and index; $45.

A review in three parts

SAN DIEGO — For many readers, the takeaway from the 731 pages of text in Max Boot’s Reagan: His Life and Legend will be that President Ronald Reagan took direction from his subordinates, and depending on which ones he listened to, the results either were very good or disastrous.

SAN DIEGO — For many readers, the takeaway from the 731 pages of text in Max Boot’s Reagan: His Life and Legend will be that President Ronald Reagan took direction from his subordinates, and depending on which ones he listened to, the results either were very good or disastrous.

The 40th U.S. President had some smart, savvy advisers such as Jim Baker, Dick Darman, George Shultz, Colin Powell, Howard Baker, Ken Duberstein and Frank Carlucci, according to biographer Boot. Those with whom he would have been better off without included Al Haig, Bud McFarlane, John Poindexter and Don Regan. I would add to that list the antisemite Pat Buchanan, who at the time worked in the White House Communications Office.

After Reagan acceded to a request by Germany’s Chancellor Helmut Kohl to visit a German military cemetery on the 40th anniversary of the end of World War II, it was discovered that 47 members of the Waffen SS — the Nazi paramilitary organization loyal only to Adolf Hitler — were buried at that cemetery in Bitburg, Germany. Holocaust Survivor Elie Wiesel, visiting the White House to receive a congressional gold medal, advised Reagan: “That place, Mr. President, is not your place. Your place is with the victims of the SS.” Buchanan, on the other hand, urged Reagan to make a point of the visit, to show he was not “succumbing to the pressure of the Jews,” according to biographer Boot. White House Deputy Chief of Staff Mike Deaver, who foolishly had advanced the 1985 visit, partially redeemed himself by arranging that Reagan also visit the Bergen-Belsen Concentration Camp, where Anne Frank died, and memorialize the victims.

My attention was drawn while reading this biography to the role and relationships that my fellow Jews had with Reagan. In a section on Reagan’s roots and early life, Boot reported that Reagan’s father, Jack, was a shoe salesman who “refused to stay at a hotel that would not admit Jews. He was said to have spent the night in his car, contracting pneumonia as a result.” Perhaps in emulation of his father, Ronald Reagan “resigned from the posh Lakeside Country Club in 1946 once he learned it did not admit Jews and instead joined the Hillcrest Country Club, which had many Jewish members, including Jack Warner.”

Warner headed the Warner Brother Studios, which started Reagan as a contract actor in 1937 and shepherded his career from bit parts to those of a supporting actor and occasionally a leading actor. By 1941, the studio agreed to a seven-year contract, negotiated by Reagan’s Jewish agent Lew Wasserman, that paid initially $1,650 per week. It rose after three years to $3,000 a week and culminated in the contract’s final year at $5,000 a week. In the post-war era that kind of salary had much more spending power than it has today.

Yet in the late 1940s, Reagan complained that he could not get the parts he wanted, but instead was stuck with being a “goody-good.” He expressed to an interviewer the wish “if only I could play a scoundrel, or a murderer, or get a good case of madness.” He was particularly miffed that he lost a leading role to Errol Flynn in the forgettable 1950 movie Rocky Mountain. Sixteen years later when he was running successfully for California governor, he renewed his suspicion that Warner held his career back. The movie mogul was widely quoted as saying, “Reagan for governor? No, Jimmy Stewart for governor, Ronnie Reagan for best friend.”

Reagan had spent the war years making patriotic films for the U.S. Army at a studio in Culver City. Raw film footage from the front would come to the studio to be spliced into newsreels, and Reagan was particularly horrified by those shot by American soldiers who liberated the Nazi concentration camps. As U.S. President from 1981 to 1989, he described those films in such detail that visiting Israeli Prime Minister Yitzhak Shamir in 1983 and Nazi hunter Simon Wiesenthal in 1984 were convinced he actually had visited the camps.

Reagan was elected as California’s governor in 1966 and among the first controversial issues he had to confront was a bill by State Senator Anthony Beilenson, a member of Beverly Hills’ Jewish community, to permit “therapeutic abortions” in the cases of rape, incest, or if the prospective mother’s life was endangered physically or mentally. Reagan warily signed the legislation, encouraged by Beilenson’s cousin Larry, an attorney who represented Reagan while he had served as president of the Screen Actors Guild. Later, Reagan said signing that bill into law was one of the biggest mistakes he had made in his career, arguing that “the fetus is a living human being and an abortion is the taking of human life.”

After Reagan was elected to the presidency, he chose a Cabinet that was devoid of Jews, Hindus, Muslims, Latinos, or Asian Americans. However, he selected economics professor Murray L. Weidenbaum to chair his Council of Economic Advisers, who compliantly endorsed Reagan’s 1982 budget assumptions of 5.2 percent real economic growth and 7.7 percent inflation. “The actual figures for 1982 would turn out to be minus 1.8 percent growth and inflation of just 3.8 percent,” the biographer reported.

Subsequently, Martin Feldstein, who succeeded Weidenbaum, said Reagan was told by his staff that it would be okay to pass some tax increases because Democrats had promised to deliver three dollars of spending cuts for every dollar of tax increase — a fiction that Reagan trusted but hadn’t verified. “Reagan had fallen prey to his own inattention to detail, his extreme delegation of authority, and his penchant for wishful thinking,” Boot asserted

What to do in regard to the Soviet ‘refuseniks” — Jews who wanted to emigrate to Israel or the United States but were refused permission and then stripped of their jobs — was an issue that justifiably complicated U.S. relations with the Soviet Union. Reagan met in May 1981 with Avital Sharansky, the wife of imprisoned refusenik Anatoly Sharansky (who later took the name Natan Sharansky). After the meeting, Reagan wrote in his diary “D–n those inhuman monsters. [Sharansky] is said to be down to 100 lbs & very ill. I promised I’d do everything I could to obtain his release & I will.”

Two years later, while still imprisoned in the Russian gulag, Sharansky learned that President Reagan had referred to the Soviet Union as an “evil empire.” Critics lambasted Reagan on the grounds that such a speech retarded efforts at detente, but Sharansky called it “most glorious” because Reagan had “made it impossible for anyone in the West to continue closing their eyes to the real nature of the Soviet Union.”

In November 1985, Reagan brought up the issue of Soviet refuseniks during a summit in Geneva, Switzerland, with Mikhail Gorbachev. He told the Soviet leader that if he allowed the Jews to emigrate, Reagan would “never boast that the Soviet side had given into the U.S.” Sharansky was released in February 1986 in an exchange of the two countries’ detainees. The freed prisoner went to Israel, where he would serve in the Knesset and later as head of the Jewish Agency for Israel.

*

Part 2 tomorrow: President Reagan’s fraught relationship with Israel

*

Donald H. Harrison is publisher and editor of San Diego Jewish World.