Second of two parts; Link to Part One.

By Alex Gordon

HAIFA, Israel — My Father, a professor of French and German literature at Kiev University, loved the work of the German poet Heinrich Heine. He wrote books, articles and defended his doctoral dissertation on Heine’s poetry. For his adoration of the “petty-bourgeois” German poet of Jewish origin, Father was accused of preferring foreign literature to Soviet literature and of writing about bourgeois writers and glorifying their work instead of praising Communist writers.

In 1949, Father was dismissed from the University of Kiev and from his position as editor of the main literary Ukrainian journal, Rodina, and ostracized. He made the mistake of thinking that praise for Heine, friend of Karl Marx and idol of Friedrich Engels and Vladimir Lenin, would reliably protect him from being labeled a “rootless cosmopolitan,” a “passportless vagrant,” i.e., a person who did not deserve to have a homeland. After three years of wandering, he found himself in Soviet Central Asia. Beaten by the Soviet regime, he looked for another, safe subject for his literary research and found…

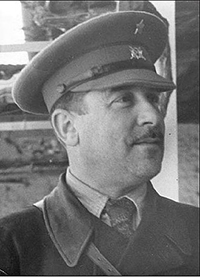

Father’s first three books, published after the cosmopolitan campaign, were written about the Hungarian communist writer Máté Zalka. This “proletarian” writer, who had long lived in the USSR and was loyal to the Soviet regime, became a legendary hero of the Spanish Civil War and died at the hands of the Frankists under the name of General Lukács, commander of the 12th International Brigade: in 1937 he was killed in a bombing raid on a highway near the town of Huesca.

The Hungarian- and Russian-fluent writer, communist, red commander, internationalist, hero of two civil wars – in Russia and in Spain – was a reliable object for Father’s work. Working on books about the Hungarian writer was a great way to make Father forget the annoying “flaws” in his biography. Zalka was far more reliable than his favorite Heine. But Jewish danger also awaited Father in connection with his new hero. Father did not realize that he was writing about a Jew again. Béla Frankl-Máté Zalka- General Paul Lukács was a Jew!

The secret of Máté Zalka’s Jewish origin was kept much longer than the secret of General Lukács’ origin. The first hero of Father’s purge of “cosmopolitanism” was, ironically, a hidden Jew and, by the definition of those years, a “cosmopolitan.

”Máté Zalka would certainly have been a victim of Stalin’s repression in 1937 if he had not died in Spain.” In his memoirs, Father quotes the words of Zalka’s widow, Vera, spoken during a meeting with him. The meeting was also attended by the sister of Stalin’s wife Nadezhda Allilueva, her brother’s wife, the doctor-writer Raisa Azarkh, Máté Zalka’s mistress who served in his Spanish brigade, and his adjutant, the poet Alexei Eisner: “How fortunate that Máté died there. What a terrible fate would have awaited him here.”

If Máté Zalka had survived in Spain and returned to the USSR, he would not have retained the title of Hungarian Communist writer and would have lost the title of hero of the Spanish Civil War. A great many Soviet participants in the Spanish Civil War were subjected to repression. But if Máté Zalka had returned to Russia and survived 1937, he would probably have shared Father’s fate: he would have been exposed for concealing his Jewish origins, his pseudonym would have been revealed, his real Jewish surname would have been exposed and condemned, and he would have been branded “cosmopolitan,” and accused of dangerous foreign connections, and perhaps even espionage.

However, Zalka ended his life in Spain. Before his death, he managed to write his novel Doberdo about the First World War, which centers on one of the bloodiest battles of that war, held near the Italian village of Doberdo. Zalka critically describes the absurdity of warfare and unequivocally condemns the perpetrators of the world war. Criticizing and condemning the “imperialist” war, the writer Mate Zalka calls for a Civil War. Having actively participated in two civil wars, he calls for a new civil war as a method of winning communism, knowing from his extensive Soviet and Spanish experience the atrocities of civil wars.

Zalka saw in socialism and internationalism the solution to the Jewish question. In a paroxysm of internationalism, he became the hero of three nations, Hungarian, Russian and Spanish. He did not, however, become the hero of his own people, the Jewish people. But proximity to the hero is not always safe. Father, who had relatively recently escaped from “cosmopolitanism” by choosing Máté Zalka as his hero, came close to a powder keg. Almost all of Máté Zalka’s Soviet associates were executed and posthumously rehabilitated. The writer Zalka was “rehabilitated” by death itself.

In the fall of 1956, there was an uprising in Hungary against the pro-Soviet Stalinist regime, called in Soviet historiography a “fascist rebellion” prepared by “Western agents against the Communist government.” The end of the finished edition of Father’s first book about Máté Zalka – 10,000 copies – had to be urgently revised, because the author had carelessly written in it that “the Hungarian Workers’ Party was rapidly leading the people to socialism,” but it turned out that it was leading them to anti-Sovietism.

Immersed in the subject of Máté Zalka, Father socialized with Hungarian communist emigrants who had fled to the USSR. During the Hungarian uprising, Father, the only biographer of Máté Zalka at the time, was summoned for interrogation by the KGB. This was seven years after he had been repressed for “cosmopolitanism,” but Stalin had already died, and Father survived this time.

In the analysis of Zalka’s work, Father, who suffered persecution because of his adoration of the Jew Heine, was balancing on the brink of a new danger because of his praise of the Communist Jew, Zalka. This hero could easily have become an anti-hero.

*

Alex Gordon is professor emeritus of physics at the University of Haifa and at Oranim, the academic college of education, and the author of 10 books.

As always, another fascinating article by Alex Gordon.